FOREWORD

Water Urbanism

Water is constantly in motion, changing states, crossing borders, nourishing (and destroying) life. How can water and urbanism be considered together as a generative frame for urban design practice, social life, and ecological regeneration? The spring semester 2018 urban design studio investigated urbanization challenges in Varanasi India, one of the most significant religious sites along the Ganges River. Our goal was to develop a comprehensive understanding of water systems and social life and how these systems interrelate with a specificity of context, land, economics, religion and urban-rural pattern. Student projects for re-imagining Varanasi combine the exploration of water, economic, social, spatial, and power dynamics to propose resilient urban forms. Rather than “solve problems” and advance land-centric modes of development we aimed to envision an alternative conception of infrastructure and the city centered on water systems, landscape revitalization, health and equity.

Columbia UD Faculty: Kate Orff (studio coordinator), Dilip DaCunha, Geeta Mehta, Julia Watson

Introduction

From Anandavana to Varanasi

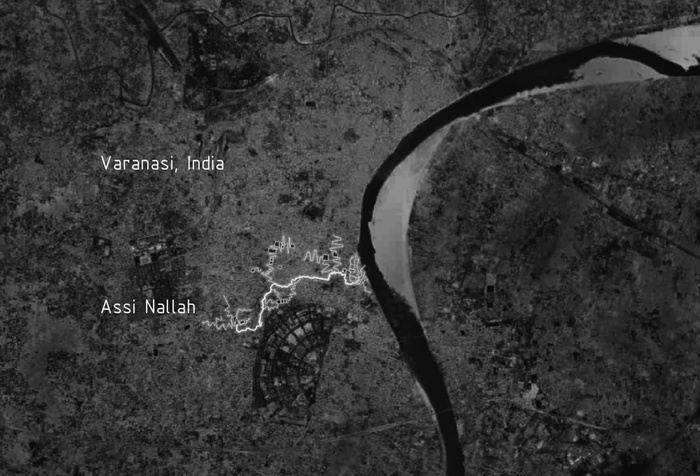

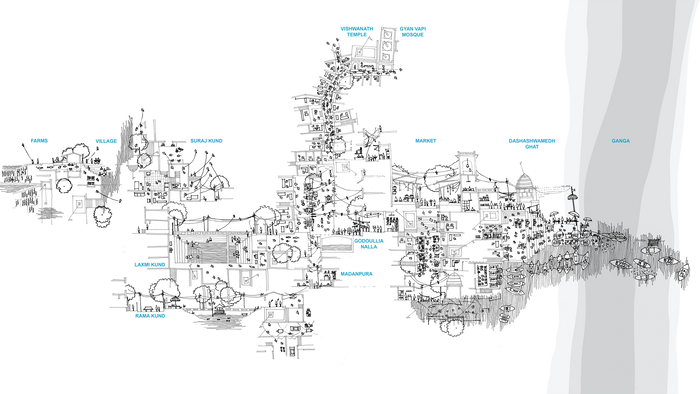

Varanasi was once known as the Forest of Bliss, or Anandavana. It has been a spiritual hub for Hindus and Buddhists over centuries and today is a bustling city with incredible pressures on its infrastructure. Located between the “Assi” nallah and “Varuna” river – the chapters of which also frame this publication, the city today faces urban pressures typical of modern Indian city including the degradation of traditional water management methods that have been halted and destroyed; the Neglect of talabs and rainwater management; mass deforestation, pressure and development focused on the River “front” while the inland interconnected water bodies are neglected; air and water pollution; public health and the increasing domination of private motorized vehicles dominating public spaces. At the same time, we do not see Varanasi as consisting of problems to be “solved” but rather as a way of thinking differently about an alternative conception of development driven by a reconnection with the productive lands, with water and social life at its center, rather than by the private car and developer prerogatives.

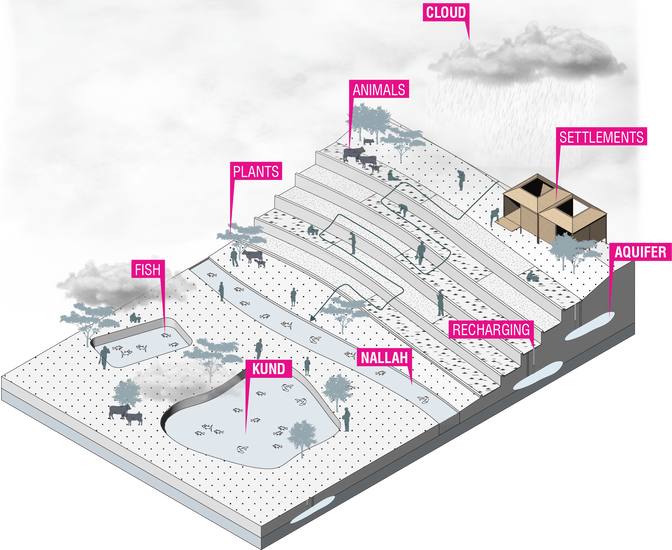

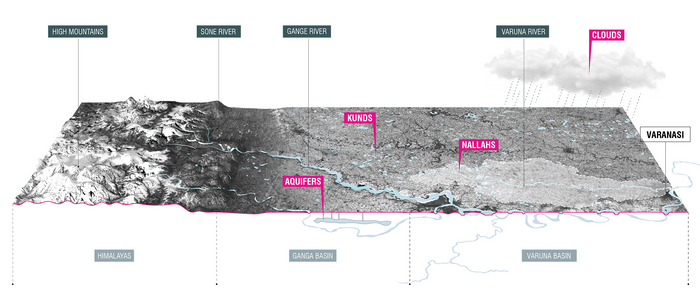

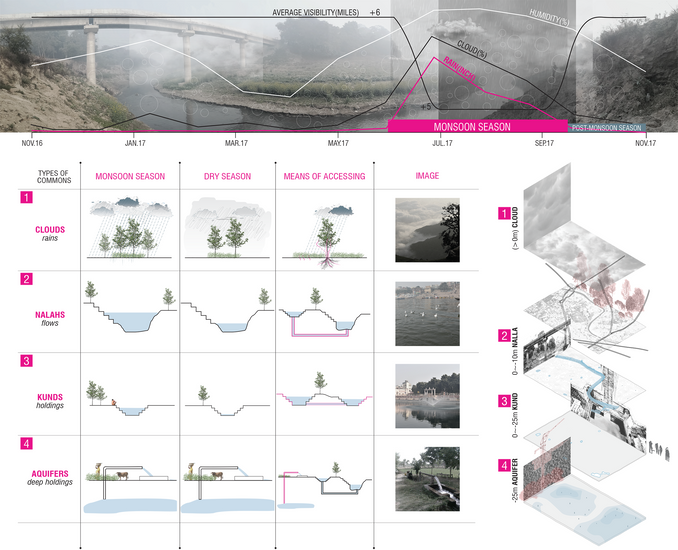

Like many cities in India and elsewhere, Varanasi is at the intersection of two water systems, as described by Prof. Dilip Da Cunha in this video: flows and holdings. The first system begins here with the River Ganges or Ganga as it is called locally. Varanasi is on the banks of this river. It extends via tributaries to points across the northern plains of India above Varanasi and deep into the Himalayas, drawing water from rain, melting snow and receding glaciers. It also extends via an infrastructure of pipes and drains to fields, industries, homes, and entire cities that draw water from it and return waste to it. This is a system that operates at a sub-continental, national and even international level, with issues that are out of the city’s control. Four major issues of concern are: waters rising with climate change beyond the already 30 to 40 feet that they do each monsoons; increasing household and industrial waste in the Ganges basin; increasing volumes of silt coming off the Himalayas that buries the ghats and fills the some temples on the ghats under many feet of mud and debris each monsoon; the project already underway to inter-link India’s rivers with siphons, dams, and canals promises to make the flow of the Ganges past Varanasi more unpredictable.

The second water system begins with the monsoons, a wind laden with rain that blows from June to September. It feeds tanks called kunds or talabs. These tanks are connected in series by their overflows, called nallahs. Once operated and cared for by local communities, tanks gave people a certain autonomy with the rain that fell in their catchment along with water from higher tanks that resulted in them making strategic relations with neighbors. Today this system is in disrepair, overwhelmed by a real estate pressures, breakdown of the local custodianship systems, water supply and drainage system that speaks the language of the river rather than the tanks, but also endangers the river. The two systems are divergent. It is a divergence that was encouraged by the English East India Company, which occupied Varanasi in the 1770s, and extended by the British who took over the governing of India in 1857 until India’s independence in 1947. Driven only by an imagination focused only on river hydraulics, they turned away from rain to rivers, constructing three sides to Varanasi: a) a “front” side on the river which is today the face of the city embellished with ghats populated by tourists and pilgrims who venerate the river ; a middle city that Mark Twain on a visit describes as a “vast mass of building, compactly crusting a hill, and is cloven in all directions by an intricate confusion of cracks which stand for streets;” and a periphery of communities around abandoned tanks, many of them built over, made into ill-functioning parks, or lying derelict and polluted.

Varanasi is also at the intersection of two modes of habitation: sedentary and nomadic. The first mode of habitation ‘originates’ on the outer bank of an ancient bend of the meandering River Ganges atop an alluvial bluff subject to erosion by the river and many nallahs. Rising sharply from the river, this bluff slopes gently to the west. The settlement on it begins as intensely urban on the river with the stone steps of ghats that have over the last couple of centuries extended to cover the entire face of the bluff. Populated with shrines, these ghats are the site of several activities from the celebrations of festivals to religious rituals to everyday ablutions. The settlement transforms from these ghats to the west, eventually transitioning from a dense settlement into a rural hinterland of villages and agricultural fields. The second mode of habitation has occurred for centuries on the sand bar across the river. It is the inner side of the bend across from the ghats that typically ‘grows or shrinks with depositions by the river. Hidden with the rise of the Ganges during the monsoons being as much as thirty to forty feet, a vast portion of this bank is exposed when the river falls. It is a place for agriculture, grazing and the temporary settlements of nomadic pastoralists, craftspeople, musicians and others who crisscrossed the northern plains, more so in the past than today.

Columbia Faculty: Kate Orff, Dilip da Cunha, Geeta Mehta, Julia Watson

Special Advisors: Prof. Joy Sen, PhD, Prof. Arkopal K. Goswami, PhD, Prof. Bhargab Maitra (IIT), Students and Faculty of Banaras Hindu University

Essay

Restoring Agency to Urban Stakeholders Through Social Capital

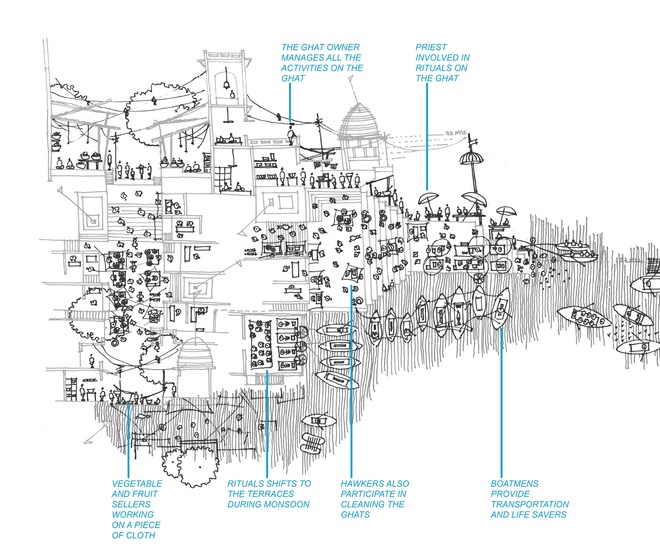

The sight of the majestic waterfront ghats, or steps leading down to the Ganges in Varanasi is unforgettable. From the twilight of dawn until after dusk, hundreds of thousands of pilgrims crowd along these steps to bathe in the sacred waters. Probably one of the most intensively used public spaces anywhere, the area is surprisingly clean and well maintained, unlike the rest of Varanasi, where trash heaps pile up in the streets, kunds (tanks), ponds and green spaces are neglected, and the overall level of city management leaves much to be desired.

The explanation for this sharp contrast lies in the matter of leveraging or ignoring the agency and civic engagement to the people of Varanasi. Over centuries, a system of maintenance for the ghats has been developed in which responsibility for every square foot is linked to a specific temple or family. It is a system of social capital that keeps the ghats looking as good as they do. Maintenance of the rest of the city is the purview of the government, which does not have the capacity or funds to do the job. This was not always the case. While the temples nearby usually cared for kunds, ponds and public spaces were the responsibility of the people who lived around these public assets. Responsibility for managing them was passed over generations of families, who were recognized at religious or secular processions and festivals.

How can we bring that sense of responsibility and caring for the urban commons back to our cities today? Kunds in Varanasi were clean so long as people depended upon them for water. The advent of tap water has resulted in people turning their backs on kunds, and allowing their drains and garbage to pollute them due to lack of adequate sewage systems or trash collection. The connection between residents and water has been severed and social networks and social capital of communities lost. Anthony Lovin, co-author of Natural Capitalism, argues that in order to curb air pollution from cars, the exhaust pipes of the car should be mandated to vent into the passenger cabin. The technology to make zero emission cars already exists, but manufacturers have no incentive to invest in this technology unless required to do so. Democratizing urban management, connecting people to the true impact of their actions, and developing methodologies so that people are able to help manage their environment is the key. The faculty in the studio challenged students to deeply investigate reviving the lost sense of connection between a people and their environment. To do so is the only way to build a sense of agency, responsibility for public assets, and a movement for grassroots city management in partnership with the government. People need to be empowered as citizen stakeholders, not as helpless victims of government inefficiency. There needs to be social accountability in the system, which is difficult to rely on just by replicating the systems of the past, as people are more mobile and travel across India and beyond. Challenges abound. Does our highly individualistic sense of modernity allow for such a community-based approach to the most vital functions of running a city? Does the toxic asymmetry of work-life imbalance allow time for individuals to contribute to community projects any more? What could be the mechanisms for enhancing social capital? Can modern social media and technology enable crowdsourcing of responsible citizenship? Can social capital be counted and accounted for, in a world where every thing is increasingly measured in terms of money? Might systems of incentivizing social good be more suited to the modern and more mobile lifestyles? Might pilgrims also have agency for improving Varanasi?

Urban design and architecture are social acts, so they must have a social purpose. Students’ explorations of the issues mentioned here are documented within the pages of this book.

1

Re-imagining the Assi Nallah

Students: Jesse Hirakawa, Xiaofei Huang, Marnfah (Fah) Kanjanavanit, Shih Hao Liao

What if the Assi Nallah was a productive landscape to drive social, economic and ecological development?

Our proposal aims to restore value to the Assi Nallah by creating a productive landscape along this waterway where communities can coexist.

The overall design strategy is to adapt the Assi Nallah into an articulate system of holdings and flows with platforms and folds in the landscape that treats water biotically before it reaches the Ganges. First, we will encourage locals to clean up the solid and/or plastic waste in exchange for social capital credits. Then, locals will engage in landscape manipulations to create folds in the ground to slow down water flow for treatment in anaerobic platforms and filtration landscapes. Finally, these platforms can be a starting point for economic development like hostels, working spaces, or any other public needs.

Communities will serve as stewards of the reimagined Assi Nallah and through the concept of social capital, our design will allow communities to work together to maintain and benefit from the environment.

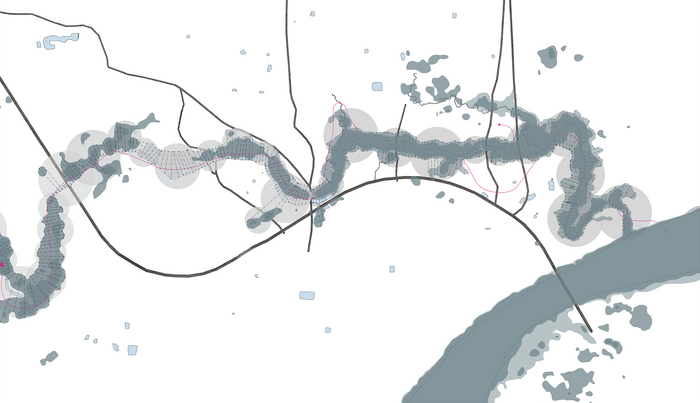

The Assi Nallah reimagined as a productive landscape: the watershed of the Assi

The Assi Nallah reimagined as a productive landscape: the origin of the Assi

The Assi Nallah reimagined as a productive landscape: the confluence of the Assi and the Ganges.

Project Introduction Video

What is a Nallah?

A nallah in Varanasi is currently an open drain that meanders through the city carrying sewage and runoff to the Ganges. These nallahs have become key conveyances in the city. Traditionally a nallah has served versatile functions, and in Varanasi a nallah was once the lowest portions of an agricultural surface, allowing water to gather and flow.

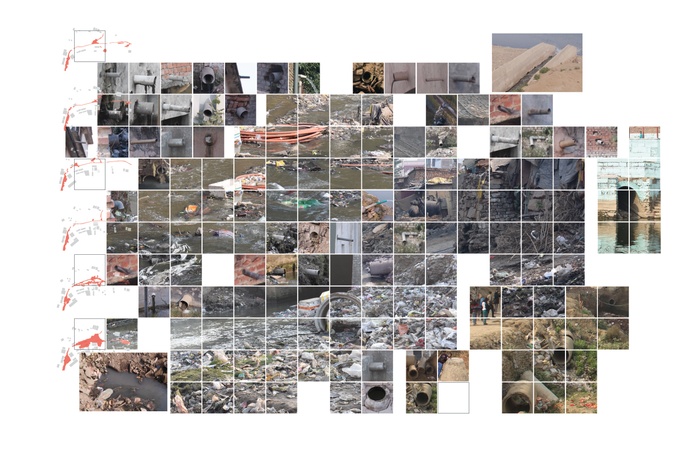

Assi nallah (crossing Nagwa Road) runs through the city as a drain collecting all runoff and waste.

Assi nallah (crossing BHU Road) as a dumping ground for trash.

Assi Nallah (along the Aditya Nagar Road) as a drain.

Locating the Assi Nallah within Varanasi

Depending on the time of year, they carried overflows of monsoon rains or were cultivated as fields of holdings. At other times they carried flowing water, appearing as tributaries of a river rushing towards the Ganges. This is a local response to the wide fluctuation between dry and wet seasons in India.

Evolution of a nallah

Rapid urbanization has caused these nallahs to fold in unnatural ways. In some areas they have become concrete or brick-lined ditches. The Assi Nallah in Varanasi has been reduced to a sewage drain.

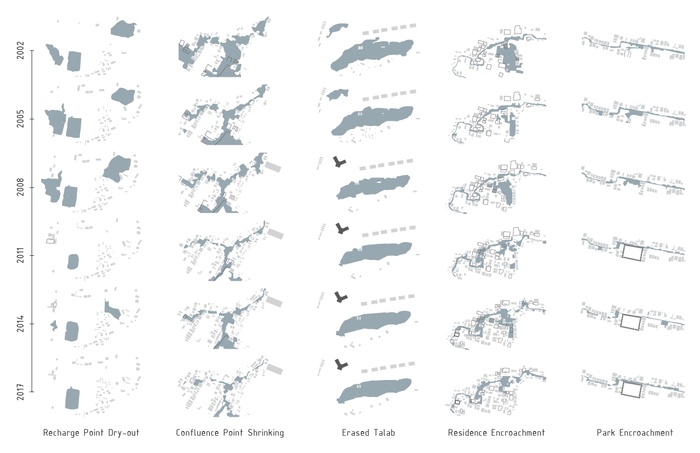

Along the Assi Nallah there were multiple forms of encroachment, our team continued to research these forms as a driver for change. The Recharge Point Dry-out and Confluence Point became two of the main factors when implementing change to the Assi Nallah.

Assi Nallah vs. the Current Sewage Treatment System

The current sewage system has an expansive network of drains to transport sewage to pumping stations. However, these pumping stations require continuous power to pump sewage to poorly maintained treatment plants. Large investments will probably not make this system successful. The current development of Varanasi’s sewage treatment system is neither strategic nor effective.

Under the government’s Ganga Action Plan II and Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) plan, Varanasi has planned huge investments in the sewage treatment system to pump waste away in non-strategic locations.

Varanasi’s existing sewage treatment system is stressed and only treats a small percentage of the sewage before releasing it into the Ganges. Most of the cities’ human waste is directed towards nallahs and not connected to a proper sewage system.

Existing sewage treatment system within Varanasi

The majority of Varanasi is not connected to a sewer line, and only 60% of the area around the Assi is connected to a proper sewage line.

The development timeline of the sewage treatment system

With projected population growth, these infrastructures and the substantial investment made towards their construction will become even more inadequate by 2035 due to the city’s rapid growth in population.

Our team wants to challenge the proposed investment of 11.5 million dollars for the new planned sewage treatment plant that may become obsolete before it gets online, versus the much smaller investment needed for the landscape filtration system proposed along the Assi, which will reap several ecological and social co-benefits.

Proposal

Our proposal aims to restore value to the Assi Nallah by creating a productive landscape along the waterway for the community to benefit and coexist.

The re-imagined Assi Nallah as a productive landscape: the watershed of the Assi

Overall Design Phasing

The overall design strategy is to adapt the Assi Nallah into an articulate system of holdings and flows, with the platforms and folds in the landscape that treats water biotically before it reaches the Ganges, and benefits the communities it flows through.

Collecting

First, locals will be incentivized to collect trash along the Nallah. They will earn social capital credits, which can be exchanged later for services. This is similar to the Carbon Credits or airline points system.

Constructing

Once the trash is gone, locals can start to transform the land for productive purposes, and earn social capital credits. The incentives for this step will be to gain ownership of land for their homes and the use of public land on the edges of the water treatment bioswales for agriculture.

Producing

Third, the area will become a productive landscape for medical and agricultural products. Platforms will start to be introduced across or near the Assi nallah to provide working spaces for agro-processing and crafts.

Building

Last, new owners will be able to receive social capital credits for providing services on these platforms: maintaining public spaces, planting trees or any other services to improve their communities.

The four phases: Collecting, Constructing, Producing and Building

Design Language - Folds and Platforms

Through a series of folds and platforms that adapt to the hydrological flow, these interventions will have multiple functions and programs responsive to the people living along the Nallah. Some will be simple interventions while some will be more complex.

Crossing platforms and terraced filtrations

Hostels with anaerobic tanks and constructed wetland filtration

Folding filtration and productive landscapes with maidans as high ground

Silt traps create temporal islands for habitat and agriculture

Ecological ghats with filtration folds

Platforms as a place of crossing and work space opportunities

Site 1 - Assi Origin

At the origin point of the Assi Nallah, existing conditions and surrounding communities inform the design of the productive landscape.

The system of folds and platforms demonstrates how a decentralized and biotic sewage treatment system can work. Since the landscape filtration system cannot treat all the wastewater, our proposal incorporates platforms that provide initial wastewater treatment by removing the solids and reducing the smell. After this step, bio-filtration takes place to further clean the water. Runoff water is also treated through these folds in the landscape that act as bioswales.

Origin of the Assi Nallah and a ritual site along a pilgrimage route

This treated wastewater and runoff water is channeled through the site into a larger water body that is designed alongs the open (maidan) spaces. Water from this water body filters into the existing kund (tank) and filters out to become the starting point of the Assi Nallah.

Our design strategy is to first complete building up the existing abandoned Kund to allow communities to conveniently use this water body for washing and fishing. Nomads, vendors, and the surrounding community can occupy the open space around the kund.

A dharamshala (pilgrimage hostel) as a platform that fits into the land while also filtering its sewage and local runoff.

These platforms of biotic sewage treatment infrastructure are expected to be owned and maintained by Uttar Pradesh Jal Nigam, an entity that currently has jurisdiction over the State’s sewer system. Farmers and maintenance workers are expected to work, on their respective sites together, to maintain this water treatment system.

On top of the platform, we propose programs such as a dharamshala (Pilgrimage hostel). These pilgrims can become a continuous source of funding for this system. Industries can be generated from the productive landscape such as food processing, bamboo crafts, Ain wood production, medicinal plant production, etc.

This system of folds and platforms accommodates the flux in water levels between dry and monsoon seasons.

Site 2 - Assi and Ganges Confluence

At the confluence of the Assi and Ganga, this project celebrates this holy intersection by transforming an existing park into a delta of temporal productive landscape- for use by pilgrims and able to accommodate the flood waters of the monsoons.

This system of folds and platforms will demonstrate how sediment flows through the confluence. Ultimately, trapping the silt and sediment from the river and nallah.

Confluences are traditionally sacred places where the Assi Nallah and Ganges river meet will now be celebrated.

The ghat area has been designed as a series of landscape folds that filter runoff before it flows into the Ganges River. These folds also create terraced platforms for temporal agriculture.

The landscape folds in between the the existing communities and weave in to occupy the new ghats, activating the adjacent public spaces. Since the Assi Ghat area is a popular location for guest houses and many tourists to go, a vibrant public space can attract tourists that can add to the local economy and become a source of funding to maintain these ghats.

The confluence will serve as a temporal productive landscape with filtration ghats

This proposal will enable stakeholders such as boat makers, farmers, tourists, and brick makers to take advantage of the temporal landscape.

Time iteration showing water flux from dry and monsoon season.

Like the previous site, this system of folds and platforms is designed to be resilient to the flux in water levels between dry and monsoon seasons.

3D Exploration

Through CNC modeling we were able to explore different folding typologies in the landscape.

If We Want a Clean Ganga, We Need to Start with the Nallahs

With urban nallahs running into it, it is not surprising that with the steep rise in urban population has made the Ganges, which is considered as a holy river by millions of people, among the most polluted in the world. It receives three billion liters of untreated waste everyday via nallahs like the Assi. The Indian Government, along with numerous foreign and local entities have invested considerable amounts of money, time and infrastructure over the past 30 years into cleaning the Ganges. However, their solution of building large-scale infrastructure to intercept and treat sewage along the 2,500 km-long river is not resilient, effective, and lacks social benefits. A proposal for an alternative and more robust strategy is provided here.

2

Life-Death Cycle

Students: Tzu-ying Chuang, Zenan (Jimmy) Guo, Yiqi Mel

What if death & cremation rituals in Varanasi were reimagined as dispersed sites of regeneration and restoration on the Sandbank of the Ganges?

Introduction

Introduction

Introduction

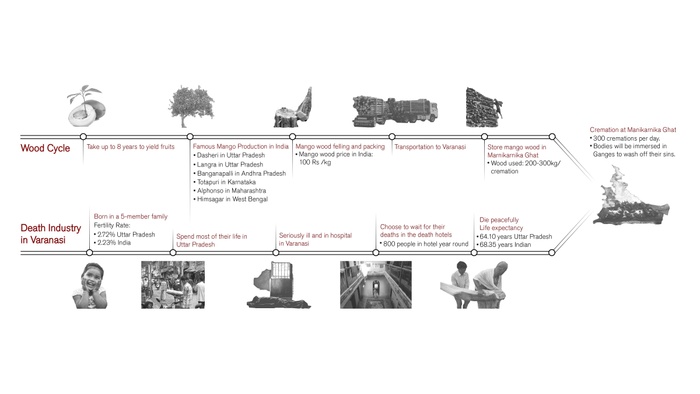

Our project focused on death rituals in Varanasi and their impact on local and regional ecosystems.

Bodies & Wood: Cremation cycle

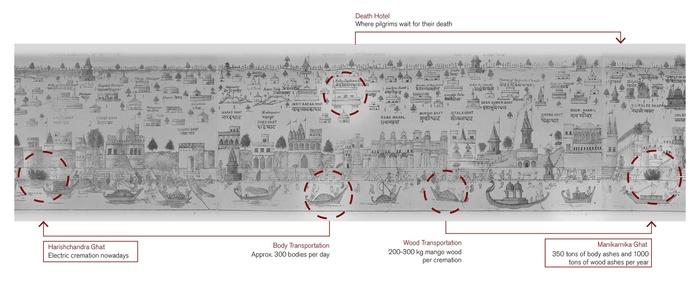

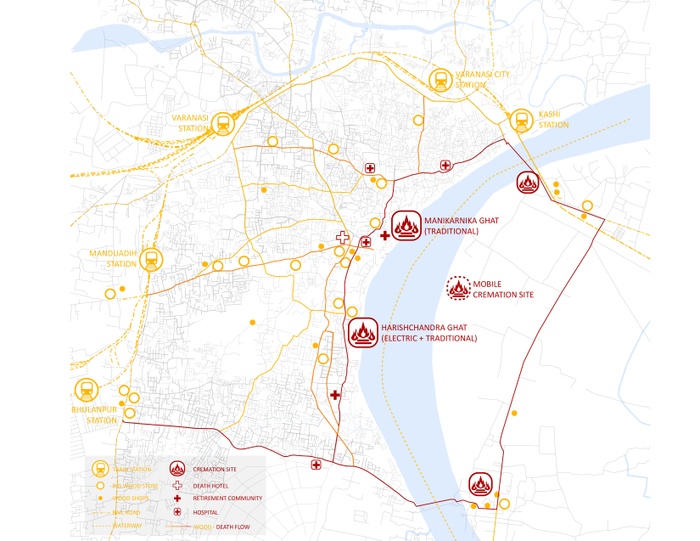

Thousands of people from India come to Varanasi each year to be cremated on Manikarnika Ghat after their deaths. Forests are decimated, and tons of wood, (especially mango wood from nearby areas) are shipped to Varanasi for the cremation process.

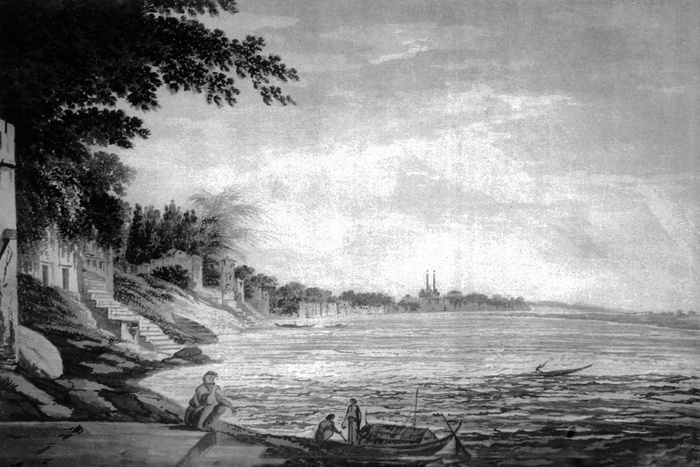

Holy city of Benares (Varanasi 1910)1

Varanasi’s death industry has great potential of being more ecologically friendly while also preserving the existing rituals and religious heritage.

Project Video

Life Death Flow (Mapping Analysis)

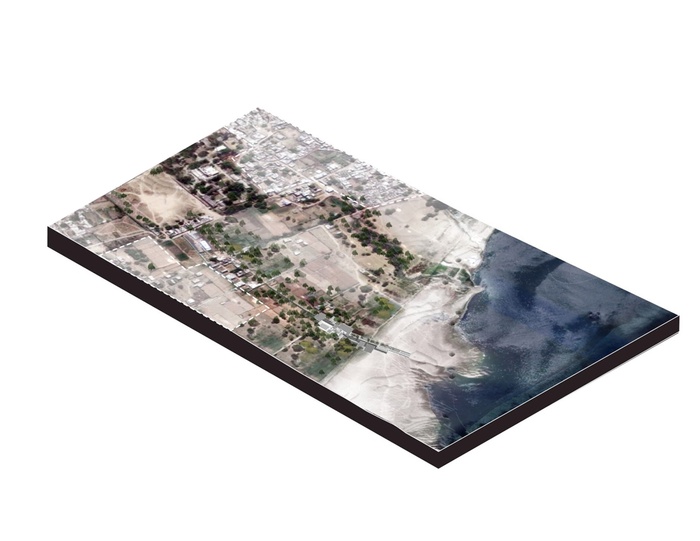

Extraction Landscapes that Support Ritual Practice (regional scale)

Current death-wood flow - pollution (regional scale)

The overwhelming increase in the demand for cremations at Manikarnika Ghat has resulted in overcrowding and pollution of the air and water.

Current death-wood flow (city scale)

The experience for families who come to cremate their loved ones is no longer as dignified as it once was in part because of the pressure of numbers. It has pushed some cremation ceremonies to the sandbank across the Ganges River. Today, with the construction of new bridges across the Ganges this sandbank is being eyed for real estate, threatening its fragile ecology.

Site Context

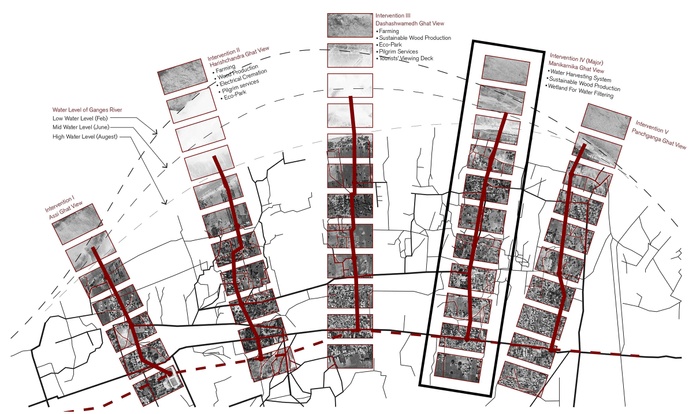

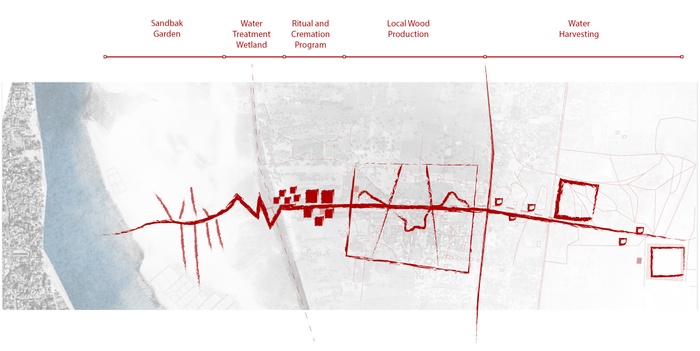

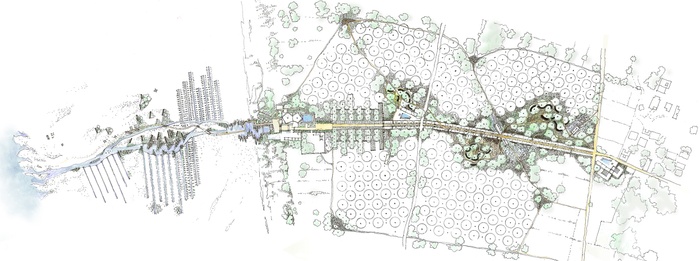

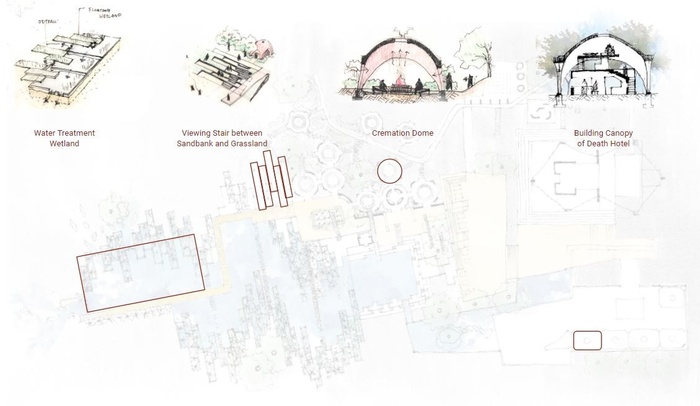

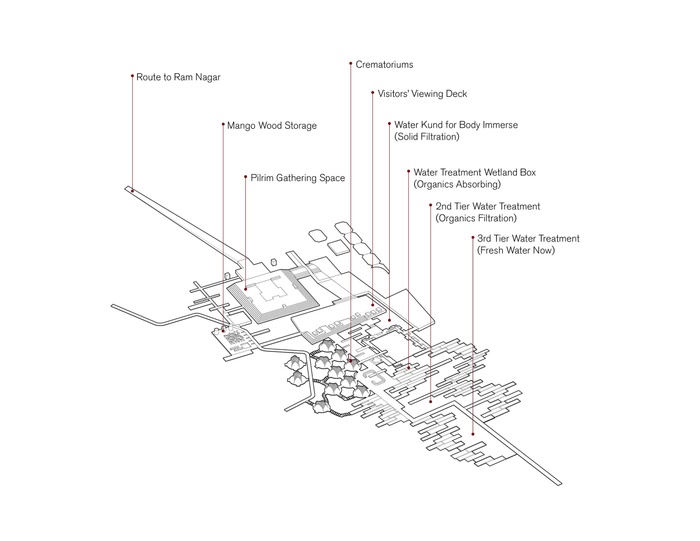

Five interventions on the sandbank across the Ganges

We therefore propose regenerative and protective infrastructures on the sandbank side of the Ganges in the form of five light-touch fingers, including one that will serve as a new cremation ground, relieving the pressure on Manikarnika Ghat.

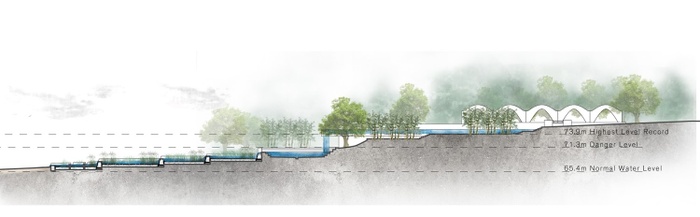

Section - site context

Connecting to existing urban context

Intervention Strategy

Journey through the new ritual landscape

We adopt strategies to heal the local and regional ecological systems of the Ram Nagar area that involve reviving existing temples and kunds (tanks), reforestation, agriculture, and settlement.

Sandalwood tree - ceremonial path

Bamboo screening - kundscape

Marigold, Sandalwood - ritual space

The ritual experience of walking in the landscape is enhanced with immersive planting.

Body ashes - Mango wood tree

Body ashes - Vetiver grass

Body remains - compost garden

We complete the death-life cycle by encouraging the mingling of ashes with soil in a ritual involving the planting of a tree. It establishes a connection between people and plants that families can visit each year and nurture.

Improve the local economy

Guide future development

Preserve cultural practices

Our project provides job opportunities in the boating, wood and tourism businesses that can be directed to local low-income communities.

Site Design - a New Ritual Landscape

Site design from Ramnagar to the Ganges

Compost Garden: Remains of un-burnt bodies will be turned into fertilizer

Pilgrim Routes: A path will allow for the ritual and sightseeing of pilgrims and tourists

Grassland: Local grasses help to hold soils

Forest Viewing Deck: Ornamental trees improve the experience of the last journey and provide shade & gathering areas

Wood Storage & Purchase: wood businesses create job opportunities for local residents

Local mango wood: Cultivating Mango trees for wood on site will reduce pressures on forests

Bamboo Production: Fast growing Bengal Bamboo will provide means for carrying bodies and assistance in burning

Cremation Dome: Self standing brick structure preserves vernacular architecture style

Sandbank Garden: Filtering water carrying ashes to the river in a terraced system will minimize pollution. The ashes will instead be directed through plants bio-remediating water

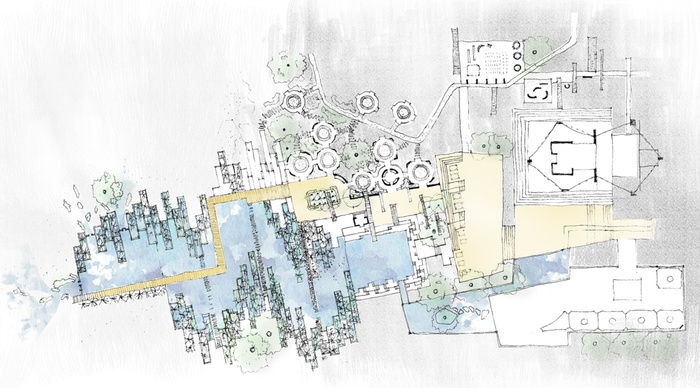

Ritual & cremation site plan

Cremation Dome & Death Hotel design module

Ritual & Cremation section

Program and Future Scenario

Life death program and water filtering system

Normal condition

Monsoon season

Ritual landscape unlocks future opportunities for reforestation and development while preserving the sandbank ecosystem

Conclusion

View towards Manikarnika Ghat from 2nd Floor of proposed Crematorium Dome

Our scheme for the sandbank side of Varanasi offers a more dignified and ecologically beneficial alternative to the current death ritual in Varanasi while respecting the traditional importance of Manikarnika. It also protects a fragile ecology and gives new life to ancient systems that integrated forestry, agriculture and water management.

1 The Holy City of Benares (Varanasi), 1910. British Library

3

Varanasi in Flux

Students: Ban Edilbi, Fatma Mhmood, Huanyu Chen, Xianyao Xia

What if all public spaces in Varanasi were flexible, adaptable and resilient maidans?

Due to Varanasi’s religious importance and the number of festivals that occur in different seasons, the population fluctuates throughout the year from 1.2 million to 6 million. 1 This flux in the number of people consists of pilgrims, tourists and nomadic groups. Nomads and workers from surrounding towns also come to Varanasi in order to sell their goods for rituals, and use Varanasi as a ground for living and production. The flux and flow through Varanasi is not limited to people, but also to the annual rainfall which changes the landscape, the celebration of festivals, migratory birds that come from Siberia from November to March, and seasonal flowers that are used in festivals.

The Varanasi Development Authority has prepared a 2031 Master Plan that is meant to expand the city to accommodate the growing population. Our project challenges the 2031 Master Plan by looking at Varanasi as a pulsing city rather than static and linear growth entity, where public spaces should be flexible, adaptable and resilient to accommodate the intensifying seasonal flux of people, flora and fauna.

Project Video

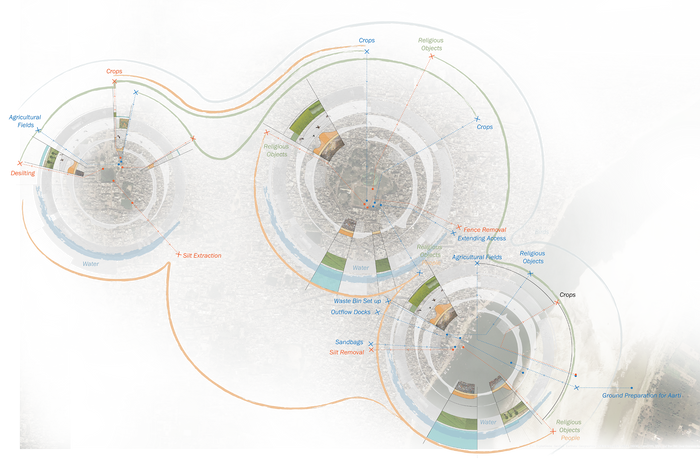

Actors in Flux

We analyzed the layers and flows in Varanasi and linked the flows to four actors: the people that come for festivals, the fauna that is grown nearby, the migratory birds that occupy the Ghats and the Sandbank, and the Ganga River’s dynamic edge that defines the Ghats and the Sandbank.

Identifying the actors in Flux

Elements and Beneficial Transactions in a Socio-Ecological Community

We analyzed the flow of our four actors through Varanasi, to understand where they originate, and the beneficial transactions between them, and noted the following:

- The pilgrims and tourists coming from all over the world are a major trigger for commercial activities in Varanasi. The nomadic Banjara tribal population coming from Rajasthan also add to it.

- The migratory birds that fly from Siberia to the wetlands in Varanasi and the Ghats create an attraction for bird watchers and therefore an income source for boatmen.

- The diverse flora species that grow around Varanasi include native species as well as those from South America, Australia and Europe.

- The flow of the Ganga River that causes dynamic changes in the Sandbank due to Monsoon and seasonal changes

The trajectories of the four actors

Beneficial transactions between the four actors

Cycles of Flux

We have traced the cycles of our actors throughout the year in Varanasi, and how they fluctuate in different seasons in relation to cycles of monsoon, migration, cultivation, and celebration. The flux of birds occurs between November to March. Festivals that attract tourists and pilgrims coincide with harvesting seasons to celebrate good harvest, and water affects them all including festivals and crops.

The flux of people, birds, flora and water throughout the year

Makar Sankrantri, or the kite Festival that takes place every year in January

Shravan Mas is one of the wettest months of year

Dev Deepawali, or the festival of lights, is one of the busiest festivals witnessed in Varanasi

Adopting the Maidan Concept to Accommodate Flux

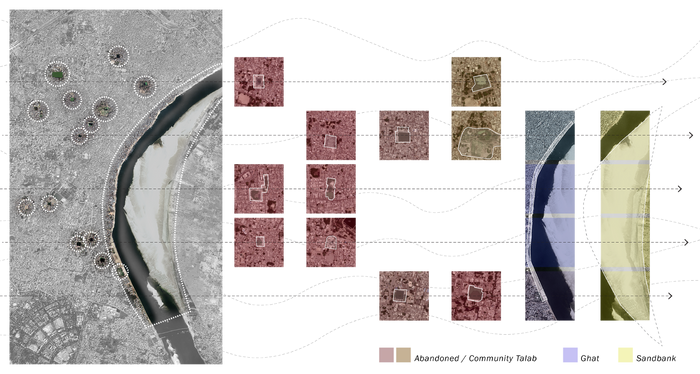

Our proposal adopts the concept of maidan, which is an open space that allows for flexibility in program, porosity, density of users, and adaptability to different seasons. Talabs, parks and the edges of the Ganga River are common public spaces in Varanasi. They are identified as potential maidans which can be transformed into seasonal, adaptable and resilient spaces to absorb the intensifying flux.

Current approach to planning

Proposed approach to creating urban spaces

Expansive networks of Maidans

Talabs, parks and the edges of Ganga as potential Maidans

Site Typologies

Three types of flexible public spaces, where the flux is most concentrated, were chosen to test how they perform in relation to the calendar. These are Chakra Tal (pond), Beniya Park and the Ganga River’s dynamic edge. Design strategies will be developed for each site typology, which can be used to transform similar public spaces into maidans in other locations too.

Chakra Tal, Beniya Park and the Ganga River’s edge are future typologies of seasonal, adaptable and flexible maidans

Maidan Infrastructure

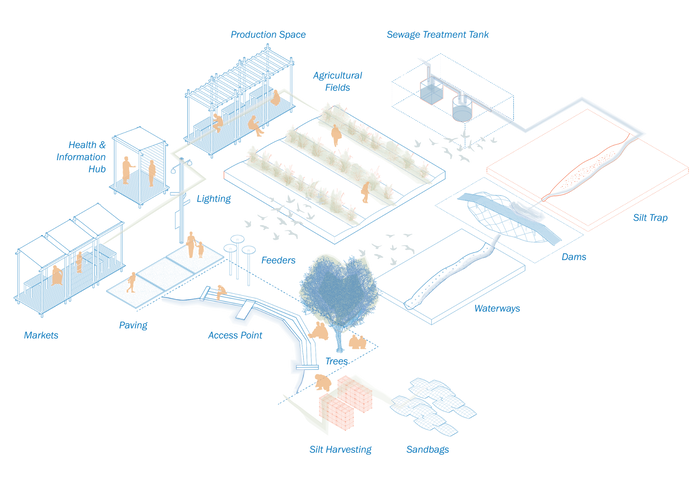

The infrastructure of a maidan consists of two types, permanent and temporary. The permanent infrastructure has been designed to appropriate the sites to be adaptable and flexible. It is designed to provide direct access from the city fabric to the maidans by removing fences and physical barriers, and enabling the maidan to become an extension of the pavement from the alleys. Dense trees are planted along the periphery to define the maidans to prevent encroachment and provide shade. The temporary infrastructure is designed to allow the maidans to perform in response to different seasons. A kit of parts that can be aggregated and amplified to accommodate the flux of religious tourists has been proposed to create this temporary infrastructure. The material palette of the infrastructure is based on locally sourced materials that can be self-organized and locally managed.

Permanent Infrastructure

Wayfinding infrastructure to provide a direct access from the dense urban fabric to open Maidans

Modular elements that can be aggregated and amplified in size to be inhabitable spaces for transient populations

Temporary elements that can be attached to increase the performance of the infrastructure during busy times

Manipulating the Landscape to revitalize and sustain ecosystems at talabs

Extractive and additive operations to help maintain the system and engage the locals

Infrastructure Performance in Different Seasons

The performance of each site was explored for different seasons and festivals, especially Makar Sankranti (January), Shravan Mas (July-August) and Dev Deepawali (November), to show how the infrastructure can perform at times of low water levels, high water levels and when there is a large number of pilgrims and tourists respectively. The kit of parts allows the infrastructure to be moved between the maidans depending on the seasons and the needs.

Seasonal maidans

Chakra Tal as a Maidan

Chakra Tal is currently an abandoned natural pond that once was an important social space for communities and a flourishing habitat for wildlife

Chakra Tal currently overtaken by invasive plants

Water levels have greatly receded in this water body due to lack of maintenance

The talab has become a backyard for residents, filling it with household waste

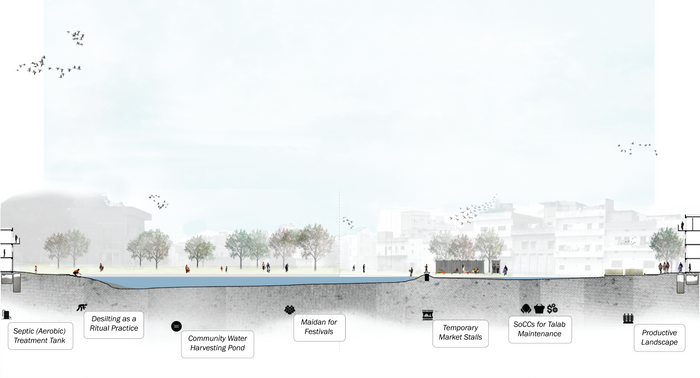

Our infrastructure aims to connect rituals with the revitalization of the talabs (ponds) by introducing dams at the entrance of waterways into the talabs to act as silt traps during the monsoon. The residents will be encouraged to harvest this silt during rituals and then use the silt in community gardens along the talab. Service hubs and market stalls are proposed at the periphery to integrate the talab with the community and to turn it into a front yard rather than a backyard, the way it once used to be. Sewage treatment tanks are proposed to purify the water from the residential developments into the talab and to sustain the talab ecosystem.

The kit of parts engages residents in maintaining the talab and sustaining the ecosystem

The images show how the talab can be integrated into the community as a front yard rather than an abandoned backyard, while responding to different seasons: with commercial activities during Dev Deepawali, to store of water during Monsoon, and for seasonal agriculture.

Commercial and agricultural activities during Dev Deepawali and a source for water harvesting during Monsoon

The residents around the talab will be incentivized to maintain the talab for earning Social Capital Credits by desilting and planting trees. These credits can then be exchanged for getting market stalls, agricultural produce, and other benefits. To implement this, Varanasi Development Authority can initiate changing the talab to a maidan through providing paving, dams and silt traps for talab revitalization. The residents’ associations can be authorized to manage the system of Social Capital Credits and help in training the residents to maintain the talab.

The operation and revitalization to be managed by Varanasi Development Authority and the maintenance performed by the community

Beniya Park as a Maidan

Beniya Park is currently occupied by different groups of people. Nomads use it as a temporary shelter, flute makers use it as a shelter and production space, and residents around it use it as a playground. The park is currently enclosed and fenced separating it from the surrounding urban fabric with an unfinished abandoned structure that was supposed to be a fish market and is currently used as a toilet.

Abandoned fish market and dry wetland

Playground and cricket field for residents and park users

Periphery of the park fenced off from the city

Flutemakers setting up tents and gathering spaces within the park

Flutemakers also using the park as a production space

Banjara tribe temporarily living in Beniya Park before heading to the next destination

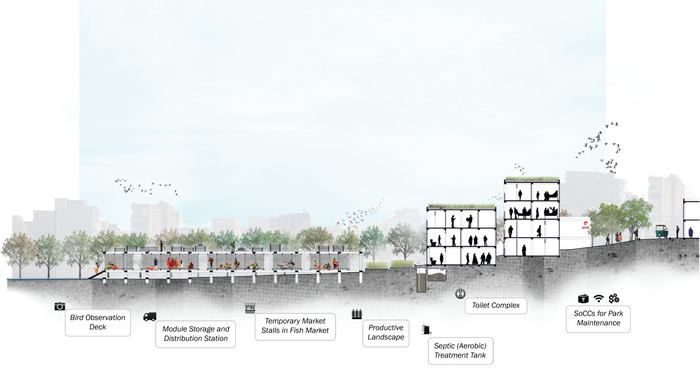

Beniya Park can be transformed into a productive maidan, with the fences removed to create a direct and continuous access. Trees can define the park and prevent encroachment. The wetland has been shown revived in the drawings to function as a bird habitat. The kit of parts shows the temporary elements that correspond to the needs of Beniya Park in different seasons. The service hubs, distribution centers, markets and shelters have been designed to serve the transient populations

The kit of parts will enable inhabitation by nomadic groups to be more comfortable?

The existing fence enclosing the park is removed to allow easy access and connect the maidan to the city’s built fabric

At Dev Deepawali time, Beniya Park can be filled with shelters and markets, while the wetland can become an attraction for bird watchers. In Monsoon, Beniya Park can be equipped with shelters and markets, accommodating the displaced activities and population from the Ghats

Revived wetland will attracts birds, and a market will serve the flux of people during Dev Deepawali time. Temporary structures will house the people and activities displaced during monsoon.

The abandoned fish market is re-adapted as a storage and distribution center for the modules. The buildings adjacent to it are adapted as service and information hubs that include toilets, money exchange and Internet facilities. The community living around the Park will be incentivized to become responsible for planting trees and maintaining the Park or for running the service hubs to get Social Capital Credits. These can then be redeemed for utility payments. To implement this, Varanasi Municipal Corporation can become a partner by accepting Social Capital Credits as utility charges

The operation and revitalization to be managed by Varanasi Development Authority and the maintenance performed by the community in exchange for Social Capital Credits

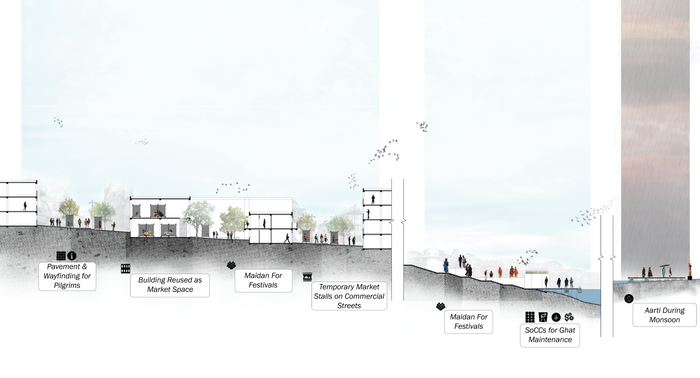

Dashashwamedh Ghat and the Sandbank as Maidans

In their existing condition, Dashashwamedh Ghat and the Sandbank lack resilient spaces and infrastructure that correspond to seasonal changes. Physical barriers along the Ghats prevent continuity of public spaces and soiled water outflow are currently contributing to the pollution of the Ganga River.

The current condition of Dashashwamedh Ghat and the Sandbank does not respond to the seasonal changes Varanasi witnesses

An extension to the edge of the Ganga River is introduced by adding floating docks and gathering points that will ease the intense crowds and provide a continuity of public spaces along the Ghats. During the monsoon season, Ghat activities can be temporarily shifted inland to seasonal markets and ponds. The kit of parts highlights the temporary elements that correspond to the needs in different seasons. The information and service hubs, and distribution centers are incorporated within the design, along with markets and shelters for the transient populations.

The kit of parts responds to the edge’s seasonal changes through temporary infrastructure

Dashashwamedh Ghat and the Sandbank as maidans

The edges of the Ganga River drastically change at times of low and high water. During the monsoon, the slower current at the Sandbank allows it to be a maidan for pilgrims and Aarti ceremonies, while it remains an agricultural and recreational space during Dev Deepawali and other times of the year.

The sandbank is a maidan for Arti during Monsoon and an agricultural land during Dev Deepawali

By incentivizing the Ministry of Tourism to be responsible for adding way-finding and informational signage throughout Varanasi, tourists and transient populations can navigate the city. Temples along the Ghats can be given permission to temporarily move the proposed floating docks during the Monsoon to the Sandbank side.

The operation and revitalization to be managed by Varanasi Development Authority and the maintenance performed by the temples

Material Flows Through Maidans

The maidans are proposed to operate as an expansive network to accommodate the flux of materials and services to respond to the users’ needs and to maintain the performance of the sites. Public transportation may be provided to further connect the maidans where feasible. These networked maidans will ease the mobility of the four actors through the sites. Transient populations will have information to use these maidans. Crops grown in the community gardens around the talabs can be moved to the markets in Beniya Park and the Ghats along this network. During monsoon, the displaced population from the Ghats can move along this network to shelters and markets at Beniya Park.

Maidans operating as a network through easing the movement of the four actors identified previously

Conclusion

In order to prepare Varanasi as a pulsing city that accommodates the flux, public spaces can be made resilient by making them flexible, adaptable and seasonal, i.e. like maidans in the true sense of this space typology. This is essential for the future of Varanasi as the flux of people intensifies due to increasing demand, and the water level rises even more due to climate change.

Varanasi 2050 vision

1 “The Indian And Foreign Tourist Visits In Important Tourist Places Of Uttar Pradesh In Year 2011 To 2015”. 2018. Uttar Pradesh Tourism. http://www.uptourism.gov.in/site/writereaddata/siteContent/tourism-stats.pdf?cd=MwAwADcA.

4

High Ground + Low Ground

Students: Yanmin Bao, Yuqi Cui, Caroline Jeon, Yeonkyu Park

What if a strategy of sculpting the landscape into High Ground and Low Ground became a model for future Ganga floodplain urbanism?

High-Ground + Low Ground: Ganga Floodplain Urbanism proposes an innovative strategy to improve the livability as well as the economic and social conditions of residents in the heavily populated floodplain along the Ganges River. Instead of annual inundation and hardship in low lying areas inhabited by poor and migrant populations, a strategy of sculpting a low-ground + high-ground landscape allows people to live safely on high ground while the low-ground is used for seasonal agriculture and the easy drainage of high waters. In this way the low-ground sites in and around Varanasi can be safely inhabited.

Floodplain Urbanism in Varanasi

Existing Elements | Mohalla

Existing Elements | Watercatchment

Existing Elements | Bund

Existing Elements | Agriculture

Existing Elements | Levee

Existing Elements | Drain

Existing Elements | Port Development

Project Video

Incremental Floodplain Development

In the floodplain site between the Ganges River, the Ring Road, and Banaras Hindu University, we propose a settlement strategy of ‘fingers of high ground’ by using a combination of soil from cut and fill operations and dredged river silt to build the fingers. This will be followed by an incremental building strategy on top of the fingers based on the mohalla, a prevalent neighborhood typology in Varanasi. The low-ground areas between the fingers will become capable of draining water to the river during monsoons while serving as ground for urban agriculture during the rest of the year. Infrastructure and transportation is also proposed along the spine of the fingers, which will enable people formerly living on the low-grounds to have better connections with the city and its infrastructure, and live with resilience, harmony and improved economic opportunity

Floodplain Development Proposal

What is Floodplain Urbanism?

Meander is a winding curve or bend in a river that results from both erosional and depositional processes. It creates low-lying areas on either side of a river i.e., a floodplain. Currently, the floodplains along the Ganges River are unsuitable for development due to their geographical condition.

Even the Varanasi Master Plan of 2031, which proposes to expand urbanization, does not deal with the low areas which flood each monsoon. The disregarded floodplain causes hardship to the poor and marginalized people who settle in the informal settlements in the floodplains due to lack of choice.

Floodplain along Ganges River

Varanasi 2031 Master Plan

Expansion of Varanasi

Floodplain along Varanasi

National Waterway 1 Multi-Modal Terminal in Varanasi

What is the existing condition of the site?

Across the Ganges River from the site a major project is underway: the development of a multi-modal terminal on National Waterway 1 that is expected to serve cities from Allahabad to Haldia. Along the stretch of this 1620 km project, Varanasi is one of the major cities. The key benefits from this terminal is the sand and silt that will be dredged annually for the cargo ships to traverse the river. With the large amount of river silt, we propose to build fingers of high-ground to improve living conditions in the floodplain of the Ganges River. 1

Our site is the low-grounds between the Ganges River, Ring Road highway, and Banaras Hindu University. Each one of these have different development characteristics of low and high grounds.

Site Condition | Topography

Site Condition | Dry Season

Site Condition | Low-Ground

Site Condition | High-Ground

“Thousands of citizens have been stranded and are suffering due to heavy rains and water logging in Varanasi..” – Piyush Surana

Development with Existing Urban Fabric

The Ganges River, Ring Road highway, and Banaras Hindu University is the geographical high-ground infrastructure adjacent to the low-ground. Distinguishing High-Ground and Low-Ground defines the incremental operation strategy that could be applied to the low-ground.

Defining High-Ground + Low-Ground

*Three High-Ground + Low-Ground *

- The Ganges River deals with levee [high-ground] built from sand dredge, that deposits and drains the Ganga [low-ground]

- The Ring Road highway bund [high-ground] helps to connect and expand through agriculture [low-ground] and its market.

- The Banaras Hindu University is surrounded by mohalla [high-ground] settlement, a typical community formation that involves religion, occupation, and social class in Varanasi, that structures itself around an infrastructure such as, water catchment [low-ground].

Levee+Ganga Operation

Bund+Agriculture Operation

Mohalla+Watercatchment Operation

“How can we design to live with Ganga River in harmony?”

Resilient + Incremental Design Strategy

As the current low-ground sits below the monsoon flood level, the communities living there have to relocate themselves annually. To make a resilient living space in the low-ground area, this project proposes an operational strategy of three high-ground and low-grounds.

High-Ground + Low-Ground Operation

“How can we incrementally develop the low ground area to become resilient?”

Once the three operations – levee + Ganga; bund + agriculture; and mohalla + water catchment – are applied, the low-ground area can be improved incrementally by building high-ground for habitation from dredged sand and using mid+low-ground for seasonal agriculture to enhance the economy and ecology of the area.

The project proposes to begin with a finger of high ground across from the port development, then expanding both ways from there with a high-ground mohalla typology and low-ground agriculture. During the monsoon, the low lying area will drain out the flood water while leaving high-ground mohallas dry and resilient.

Incremental Development

How does a ‘finger of high-ground’ work?

With high-ground formation made up of dredged sand and silt, the new urban fabric will regenerate incrementally using a mohalla typology around water catchment structures. The mid-ground will support terraced agriculture. And the Low-ground will drain out monsoon water during the wet season and support seasonal urban agriculture during the rest of the year. It will create a new source of income that will turn informal communities into “communities in formation”.

High-Ground Finger Formation

Who are the stakeholders?

Planning in Varanasi is done by the Varanasi Development Authority. This project strategy will give them a way to develop the floodplain. Once the high-ground is built, the demand for real-estate will rise. This will justify building high-ground with the large amount of annually dredged silt from National Waterway 1 development. However, it is important that they ensure that the poor are not pushed out of this area by real estate pressures.

Levee+Ganga during Dry Season

Levee+Ganga during Wet Season

Bund+Agriculture during Dry Season

Bund+Agriculture during Wet Season

Mohalla+Watercatchment during Dry Season

Mohalla+Watercatchment during Wet Season

Conclusion

The proposed ‘fingers of high-ground’ on the low-ground in Varanasi can become a prototype for the floodplain all along the Ganges River. This model of development provides an opportunity for the vulnerable areas to house marginalized populations. The High-Ground + Low-Ground approach to urbanism can improve economic opportunity as well as bring resilience to settlement in the Gangetic Plain.

Resilient Floodplain Through the Development of High Ground Fingers

The annual rise of the Ganga cannot be avoided; we can live in harmony with it.

1 http://www.alevelgeography.com/meanders/ http://www.onegeology.org/extra/kids/earthprocesses/meanderingrivers.html

5

Forest of Bliss

Students: David Chonillo, Jorge Espinosa Gonzalez, Gigi Singh

What if Varanasi’s unique sacred landscapes could be restored through pilgrim rituals to improve urban health and ecological resilience?

The Ganga river’s severe flooding is increasing proportionally to the depletion of forests. Forests hold wetness and regulate flows. Reversing deforestation will make living in the Gangetic plain more resilient as well as increase biodiversity and provide various services at a local level.

Severe flooding along the Ganges 1

There is an urgent need to protect waterfronts on the Ganga River from floods. With the current infrastructure and resource management proving inadequate, we turn to afforestation. We see it as a means to mitigate all types of issues related to population, including health, malnourishment, pollution, pests, global warming, among others.

Future vision of the Forest of Bliss propagating from water bodies and sacred routes

Possible What if scenario

Project Video

Anandavana

Varanasi was once called “Anandavana”, meaning Forest of Bliss. This ancient place has invited millions of pilgrims to share in its spirituality and connect with it through the forest. Today, this magical landscape of the forest is lost, only seen in historic images.

Lambragraon Gita Govinda, Kangra, 1820-30, Ludwig Habighorst Collection 2

Gita Govinda, Guler, c. 1780 Victoria & Albert Museum, London 3

Radha and Krishna Meet in the Forest During a Storm, c. 1770 India 4

The loss of the forest is a tragedy for those who love Shiva and care about the pollution of his sacred body.

But it is possible to revive Anandavana.

Banaras Ghats, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, William Hodges 1798 5

Water-Spirit Connections

Recovering the Relationship Between Nature and Sacred Rituals

Hinduism centers on respect and care for nature and rituals. Pilgrim routes have always followed water bodies, giving them an importance and meaning.

Focusing pilgrims’ energy on care for nature can have an amazing impact on the ecology that surrounds them. This is a great opportunity that benefits from the number of visitors Varanasi receives each year, and will likely receive in future.

The map in the Kashi-darpana, a medieval text, includes equal parts of both sides of the river Ganga, Varanasi city side and Ramnagar side, within the culture zone of Varanasi 6

Lakes and ponds in the City - James Princep 1822 7

Varanasi: The 4-Pilgrimage circuits 7

The New Sacred Route

We propose a new pilgrim route that connects all the existing ones. Pilgrims will enter the city through Dashashwamedh Ghat, follow a course to the Varuna, and return along this river to the Ganga River.

This route abstracted as a straight path in this drawing serves as a ground for initiating a forestation strategy. We visualize the forest extending from here like fingers toward the countryside.

Abstraction of a pilgrim route through Varanasi that will begin the reforestation of the city. The staging grounds for the production and initiation of the forest are highlighted in yellow.

The three sites of intervention:

- Ghats: Fertile soil deposited by the Ganga River (especially after Monsoon) will be gathered, sculpted and carried to particular sites through rituals by pilgrims.

- Kunds: Schools and temples surrounding these tanks will coordinate tree nurseries as well as collection of cow dung and clay to produce bricks and pots.

- Varuna: This will be a site of community-based nurseries involved in transplanting trees along the river and protecting trees with brick lattices.

Axonometric views of staging grounds and seeding grounds in two different scales explaining the operations and temples involved

Sciences Behind Rituals

We work with a diverse palette of native trees and trees that will benefit people and the ecosystem. The more diverse the trees the better. The output of forest nurseries involves a complex coordination of plant growth with the calendar of festivals in order to leverage the most for the propagation of trees.

Universities can be in charge of coordinating forestry practice and social rituals.

Perspective view of a ghat where soil ritual can be performed in forest nurseries to gather fertile alluvial sediments and sculpt them on movable platforms to be carried to nurseries located at kunds

Perspective of a kund hosting a soil gathering ceremony, transplanting rituals, and production of tools like pots and bricks needed for reforestation

Perspective view of the Varuna river becoming a forest finger extending towards the horizon

Restoring the Forest of Bliss

Mitigating Severe Flooding and Habitat Depletion in the Gangetic Plain

The forest will start to grow from our proposed route toward the countryside aiming to ultimately achieve a single patch of forest cover in the future for the whole Gangetic Plain.

Varanasi should restore the Forest of Bliss as a priority

Conclusion

With a constant stream of local resources including fertile sediment, rain, cow dung, clay, and one million annual spiritual pilgrims visiting, Varanasi has the potential to become the forest it once was. The energy and dedication of pilgrims can be leveraged to propagate trees through social ritual coordinated by community-based agencies, spiritual leaders, and educational institutions. This forest aims to provide various city needs needs by infiltrating the current infrastructural system, changing the matrix, localizing resource management, building community, and starting a global ecological revolution that reclaims our neglected ecology.

1 Relief and Rescue Operations Continue in Flood Hit Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Pti - https://www.financialexpress.com/photos/business-gallery/354933/flood-in-patna-allahabad-ndrf-air-force-continue-relief-and-rescue-operations-in-flood-hit-uttar-pradesh-and-bihar/2/

2 A festival of Krishna: featuring Under the Kadamba tree, paintings of a divine love and Ateliers of love, a film on DVD, a journey of poets, painters, and patrons Harsha Dehejia - Lustre Press, Roli Books - 2008

3 A festival of Krishna: featuring Under the Kadamba tree, paintings of a divine love and Ateliers of love, a film on DVD, a journey of poets, painters, and patrons Harsha Dehejia - Lustre Press, Roli Books - 2008

4 A festival of Krishna: featuring Under the Kadamba tree, paintings of a divine love and Ateliers of love, a film on DVD, a journey of poets, painters, and patrons Harsha Dehejia - Lustre Press, Roli Books - 2008

5 Select views in India: drawn on the spot, in the years 1780, 1781, 1782, and 1783, and executed in Aqua tinta William Hodges - Edwards - 1786

6 Jayaswal, Vidula & Shukla, Uma. (2016). Summary and Deductions. 317-331

7 Benares illustrated. James Prinsep-O. Kejariwal - Pilgrims Pub. - 2009

8 Singh, Rana. (2017). Sacredscapes of Banaras (Kashi/ Varanasi): Cultural Landscape and Cosmic Geometry. Context: Built, Living and Natural [ISSN: 0973-502X; DRONAH, A-258, South city 1, Gurgaon, HA 122007, India]. 13. 11-22

6

Trans-Aggregation

Students: Donovan Dunkley, Saritza Martinez Rodriguez, Niomi Shah, Sofia Valdivieso

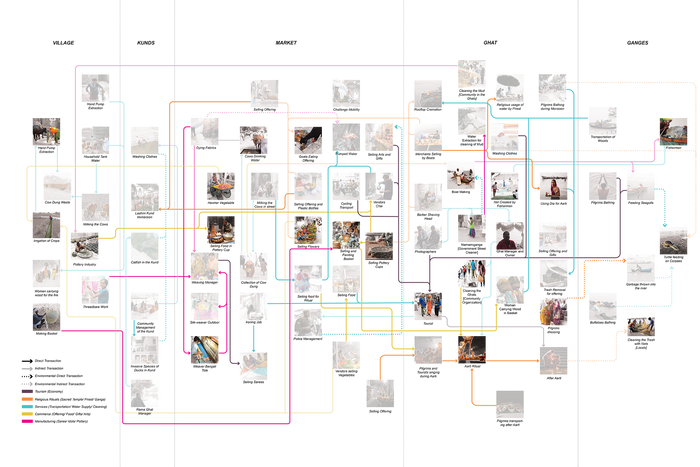

What if planning and design were shaped by hidden transactions of local social networks?

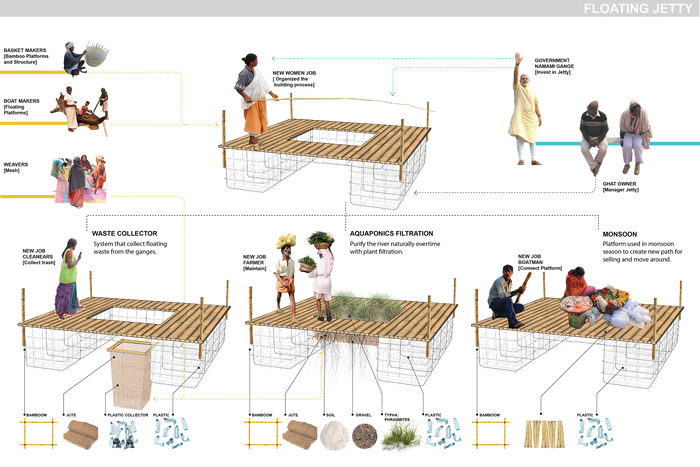

Our project challenges the top-down masterplan approach to designing Varanasi. By seeing the city as a system of transactions in the hands of people as city makers, we adopt a ground-up approach to design that recognizes that change can be generated by people who live in the area. We see transactions as dynamic sites of exchange that occur between actors on multiple scales almost constantly in Varanasi. We will focus on them as opportunities of intervention that in the future will be play a critical role of restoring the habitat and elevating the living quality of residents by addressing issues of water quality, the treatment of the city’s edge and waste management.

The spatialization of transactors

A Transaction in this context is an exchange of resources between people and the environment. The people, being agents of change, are then referred to as Transactors.

During monsoon season at Dashashwamedh Ghat

After the Monsoon

The Aggregation of Transactions

Project Video

Analyzing the Grounds of Transactions

Existing water infrastructure and the physical region of boatmen, weavers and farmers

Existing Water Infrastructure and The Physical Region of Boatmen, Weavers and Farmers

Looking at the locations of existing economies and their physical relationship with open space and existing water infrastructure, we are able to determine the agency and reach of transactors.

The simultaneity and chain effect of transactions

Reintroducing externalities

Reintroducing Externalities

Organic waste, mud and sediment, waste material from industry such as plastic, and skilled labor such as weaving and farming all become essential to the network of new transactions. Using monsoon mud deposits as a ground building material, we will be able to increase water absorption throughout the city and soften the edges of the ghats by creating slivers of green spaces that become retention sites and opportunity for filtration. The base of the ghats are then extended into the river through docks kept afloat by recycled waste. These docks contain space for aqua-agriculture. Through gravity-based water filtration, the entire city becomes a means of addressing waste management and water quality.

Transactors and their tools

Transactors and Their Tools

Unfolding the activity involved in these transactions allows us to understand the skill-set and existing incentives for local labor. The territorial ranges and materials used in this labor are then mapped out to identify the externalities created as a byproduct.

Place of the proposal

Existing nodes of micro economies

Zooming into Dashashwamedh Ghat and the associated marketplace we begin to study the granular activity in areas of concentration. We then identify the types of industry in which these transactions occur in order to determine the scale at which they can occur.

The spaces were transactions occur

The Kund as a Community

Existing condition of Lakshmi Kund

Existing condition of Lakshmi Kund

Existing condition of Lakshmi Kund

Existing condition of Lakshmi Kund

Lakshmi Kund

The stakeholders at Lakshmi Kund

Revitalizing a sense of Community at the Kund

Identifying those who already have an association with the kund and those who live in close proximity to the kund allows us to know what types of programs and activity can occupy the new community space. Each of these stakeholders will have a responsibility through their changed habitats to address the maintenance of the kund. The kund then becomes a point of commerce, public space and a source of clean water for domestic use.

Recharging the water system in Lakshmi Kund

Natural Water cleaning system

The Market as a Connector

Isolating transactions in the market

Existing condition of the market

Existing condition of the market

Existing condition of the market

Existing condition of the market

Isolating Transactions in the Market

The market is the location of transactions that are very informal. Yet each involves a particular sequence of events that include where materials come from and where externalities go. Here, we can facilitate transactions in more efficient ways while providing the opportunity for upward mobility of those who rely on these economies.

The transactors at Dashashwamedh Ghat

The transactors at Dashashwamedh Ghat

The transactors at Dashashwamedh Ghat

The transactors at Dashashwamedh Ghat

The transactors at Dashashwamedh Ghat

The market at Dashashwamedh Ghat

Transformation of the market

Our interventions allow business to be conducted all year round through the use of floating platforms that connect as walkways during the monsoon floods. Repaved streets address flood inundation of the area.

The Ghats as Public Space

Softening of the ghats and the creation of public space

Softening of the Ghats and the Creation of Public Space

It is vitally important to address the collapse of Varanasi’s ghats caused by erosion from the flow of the Ganges, particularly during the monsoon season. We do this by ‘softening’ it in parts with interventions that deploy the craft of weavers, boatmen, farmers and potters. It provides them new opportunities for employment in parallel with new skill sets that they may require and access to education through social credits. It also creates accessible public space for everyone’s use.

Existing condition of Dashashwamedh Ghat

Existing condition of Dashashwamedh Ghat

The floating jetty as a transactor

Interconnected Landscapes through Transactions

Interconnected landscapes through transactions

By seeing Varanasi as a landscape of transactions, we stop seeing elements like the river, kund, markets, ghats, etc. as land uses and recognize their connections through people as transactors operating on multiple scales. Small changes in rethinking externalities and enhancing micro economies can lead to big impacts like clean water, waste reduction, and revitalized ecologies of the city.

7

Four Commons

Students: Faisal Alzakari, Yue Hilary He, Ruilan Jia, Xiaohan Wang

What if water commons became drivers of regional/territorial planning and urban landscapes?

Tragedy and opportunity of the commons

Tragedy of the commons

Tragedy of the commons

Tragedy of the commons

Water in Varanasi is facing a “tragedy of the commons” 1. It suffers from overexploitation and severe pollution.

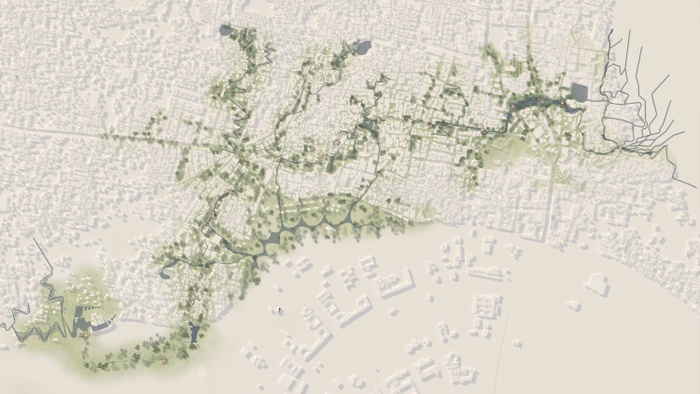

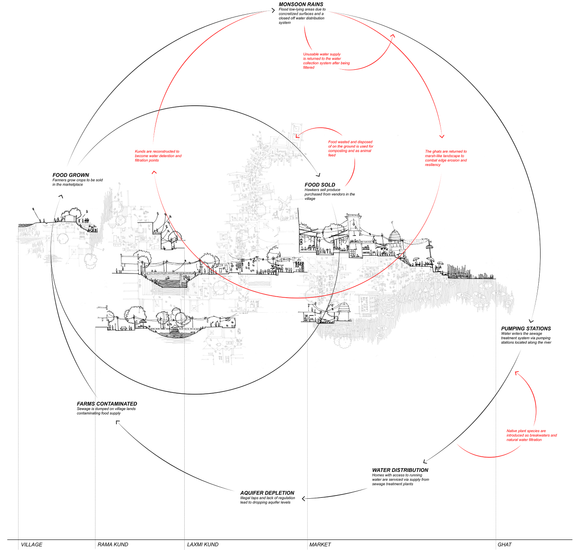

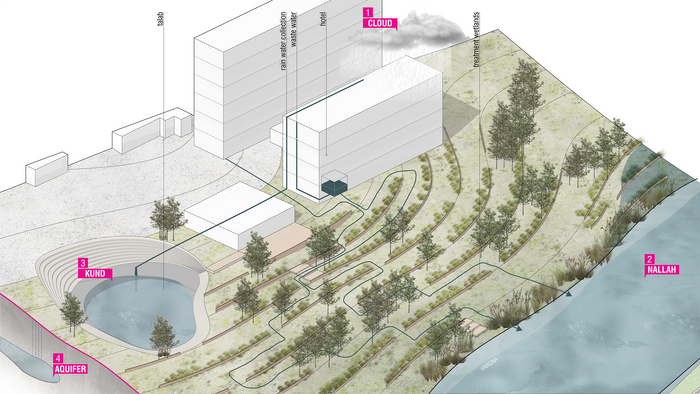

Working with water in four “commons”—clouds, nallahs, kunds and aquifers—we propose to turn Varanasi around, beginning with one of its most significant landscapes: the Varuna River. Seen as a tributary of the Ganges and now made into a drain through misuse by the city, we see it as an opportunity to transform the city from a land-based entity to one that organizes around its water commons. Identifying four water commons in Varanasi and looking at them in different time frames, we recognize that each has its own rhythms and encourages its own means of accessing and relating to water. The project explores and enhances the relationship of these four commons, allowing them to operate in a sustainable system, one that takes advantage of fluctuations in rainfall, humidity, water table depths, saturation of soil and flows.

Four Commons aims to restore the value of Varuna as a spiritual spine, a cleansing biotope and a driver of Urban Design.

What is a “Tragedy of the Commons”?

When individuals overexploit and pollute a shared-resource system according to their own self-interest, behaving contrary to the common good. This behavior leads to the loss of the resource.

Tragedy of the commons

Opportunity of the commons

From Urbanization to River-ization

Varanasi is situated between two water commons: The Varuna River in the north and The Assi Nallah in the south. The current “Varanasi 2031” Master plan proposed by the authorities is based on ring roads; it does not take into account the actual ground truths of the city’s rich landscape such as natural water bodies, whether in the form of flows or holdings. As a critique of the 2031 Master plan, this project proposes a flip in the way modern planning is practiced, by leveraging the natural water resources to become drivers of planning, beginning with The Varuna river.

From urbanization to river-ization

Four Commons

Water Commons at a regional scale

Regional water commons

What are the Four Threatened Water Commons in Varanasi?

The project identifies four water commons in Varanasi: clouds (rains), nallahs (flows), kunds (holdings) and aquifers (deep holdings). We designed this system to meet the residents’ needs for water and prevent the floods that frequently occur in the city. The project Four Commons aims to construct an environment that nurtures a diverse species of animals and plants, and one that cultivates the commons as the future of the city.

Four threatened water commons in Varanasi

Turning Varuna into a Cleansing Biotope

Varuna should not be a sewer line

Long ago, Varuna River was recognized as the lifeline of Varanasi. The pure and medicinal properties of the water nourished various types of herbs on its banks and met the needs of the city. The farmers of this area were dependent on it for drinking, irrigation and cattle rearing purposes. In the present scenario, the situation has changed drastically. Varuna is one of the most polluted rivers of India, becoming a drain that runs sewage to the Ganga. Four Commons proposes a strategy to revive the Varuna not merely as a flow to the Ganga but as a lifeline along which a city can grow and flourish.

How Do We Turn Varuna into a Cleansing Biotope?

The project’s various operations revolve around understanding the conditions of high-ground and low-ground along the Varuna River, working with the opportunity of the middle-ground.

Operation: Productive Terracing during dry and monsoon seasons

Productive Terracing

Productive Terracing places community settlements on higher ground, while the middle ground becomes terraced farmland that carries with it water run-off guided through filtration nallahs. These waterways will filter water run-off, and at some points, also serve as a holding system creating kunds or ponds along the way where clean water is stored for irrigation as well as domestic purposes.

During monsoon season, Varuna’s water level rises up, which will cover a large portion of the terraces where water will be held to fertilize the farmland. This operation also proposes tubewells as a ground-water infiltration process to recharge the aquifers. Water stored in kunds can fill the recharging tubewells to help water make its way underground.

Operation: Trash Catchment during dry and monsoon season

Trash Catchment

Trash Catchment proposes to look at a bridge not only as means of crossing, but also as an infrastructure that helps cleansing Varuna, as a trash catchment operation. The trash screen bar at the water surface level is proposed as the first layer of catchment during dry season, whereas there is a second layer of trash screen for wet season between the two levels of the bridge.

Operation: Water Treatment System

Water Treatment System

Another operation proposed is the water treatment system. We propose constructing wetlands along the Varuna River which can treat the grey water that is discharged by the surrounding buildings as well as water runoff. At the same time, we propose taking advantage of the roofs of buildings for harvesting rainwater which can be stored in nearby kunds.

Two Different Moments Along Varuna

Turning Varuna river into a cleansing biotope identifying two moments

We identify two moments along Varuna, The Crossing and The Confluence, each defined by a primary node.

The Crossing: a Cultural Node

The Crossing is a site in Varanasi with a large area of settlement between the railway track and the Varuna River. We have identified the actors who can be potential stewards, including for example, the cultural and educational institutions as well as the religious community around the area.

Urban actors of Crossing as potential stewards

Existing condition 2

Existing condition 2

Existing condition 2

Proposed Concept

After looking at the topographical condition, the high ground vs. low ground and water flow, we come to the conclusion that the city has turned its back to the Varuna River. Our concept proposes to leverage the Varuna to once again become the front of the city. With this goal, we have designed a series of holdings in the form of talabs (ponds) as well as kunds (tanks) where water flows through a filtration nallah (waterways) that starts from the railway tracks, situated on a higher level, down to the Varuna River. The idea is to be able to filter and store water at different locations. At the Varuna, we propose to soften the river’s edge to create different ecological habitat areas as well as constructed wetlands that help in bioremediation-wastewater treatment for the wastewater that is discharged by the buildings along the river.

Leveraging the river as the front of the city

Proposed Crossing site plan

Also, at the Varuna’s edge, we propose to create elevated platforms that are used as area where Aarti (prayers) can be performed and a public space that serves as a maidan (public space). We propose a farmer’s market here for the nearby eco-community. By creating a resilient river edge, Four Commons aims to activate Varuna’s edge around the year during wet as well as dry seasons.

Crossing section

Activities adapting to the changing water level

Activated edge along Varuna river

The Confluence (As an Agricultural Node)

The Confluence is where the Varuna meets the Ganga, and is bordered by existing seasonal agriculture and informal village settlements.

Urban actors of Confluence as potential stewards

Existing condition during dry season

Existing condition during dry season

Existing condition during monsoon season

Proposed Concept

After looking at the topographical condition, the high ground vs. low ground and water flow. We propose to thicken the Varuna at low points, in order to provide ecological habitat areas, while placing the eco-community settlements on higher-ground to make them more resilient. Seasonal terraced agriculture fields have been proposed in the middle ground. During dry season, the middle ground can become productive landscape and during monsoon season, it can hold water at the terraces to keep the soil fertile and to serve as a way to recharge the aquifer. Filtration nallahs (waterways) are designed according to waterflow analysis, so all sewage as well as stormwater can get filtered before entering the Varuna. The project includes various urban actors such as farmers as well as fishermen in the design process as potential stewards.

Productive landscape and settlements

Proposed Confluencing site plan

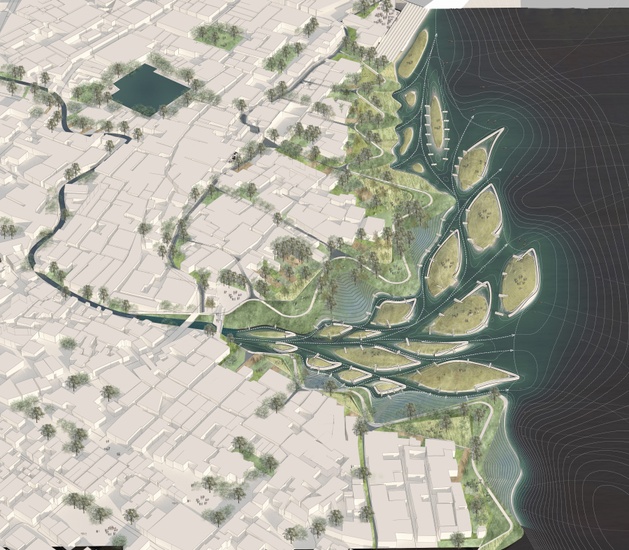

At the confluence point, we propose to open up the Varuna with a delta designed to create a set of floodable islands that serve as the last layer of water-bioremediation as Varuna enters the Ganges. During dry season, these floodable islands can become destination points for boats and tourist flows, hosting various types of public spaces as well as a farmer’s market.

Confluencing section

Operations working together on Varuna

Productive terracing adapting to changing water level

Productive terracing during pre-monsoon, monsoon and post-monsoon seasons

Conclusion

We envision the four commons intersecting in different ways, by different means, and at different times to restore the value of the Varuna River as a spiritual spine, a cleansing biotope, and a driver of Urban Design in Varanasi. This Four Commons project suggests considering water commons as the future design strategy of Varanasi, and recognizing their value as drivers of regional planning. The residents of Varanasi will, then, benefit from a water oriented city where they will have access to clean water for drinking, irrigation and cattle rearing purposes in an ecological environment that can once again hosts a diverse species of animals and plants like it used to.

Project Video

1 Garrett Hardin, ecologist, 1968 published article in Science.

2Image Credits: Kate Orff. https://goo.gl/maps/wZ2AEfE7fax

Afterword

Message from Consul General of India, New York

It is said that Benaras is older than history, older than tradition, older than even legend and that it looks twice as old as all of them put together. As a city, as a society, Benaras or Varanasi is indeed a microcosm of India. It lives, loves and evolves through a constant confluence of chaos and creativity. Varanasi is the fountainhead of the indic civilization and unites and exalts the people of India like no other city in India. The deep connect to Varanasi attracted me to joint endeavor of Columbia University’s Urban Design Program and Varanasi Design Studio of IIT Kharagpur. It was indeed befitting that the final presentations of “Rethinking Water Urbanism in Varanasi” took place in the Consulate on May 3, 2018 in the presence of academicians, students, architects and designers who worked intensively on issues related to Water Urbanism and contemporary developmental challenges in Varanasi. The designs and the presentations were indeed thought provoking and offer solutions to the problems of the city. The next challenge will be take them to the policy makers and implementers.

End

Acknowledgements

Published By:

Columbia University

Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation

Urban Design Program

411 Avery Hall, 1172 Amsterdam Avenue

New York, NY 10027

United States of America

Columbia Faculty

Kate Orff, Dilip da Cunha, Geeta Mehta, Julia Watson (Aqaba Site Faculty: Ziad Jamaleddine, Nora Akawi, Petra Kempf, Laura Kurgan) Roving Engineer: Jason Loiselle

Columbia University Students

Reimagining the Assi Nallah:

Jesse Hirakawa, Xiaofei Huang, Marnfah (Fah) Kanjanavanit, Shihhao Liao

Life-Death Cycle:

Tzu-ying Chuang, Zenan (Jimmy) Guo, Yiqi Mei

Varanasi in Flux:

Ban Edilbi, Fatma Mhmood, Huanyu Chen, Xianyao Xia

High Ground + Low Ground:

Yanmin Bao, Yuqi Cui, Caroline Jeon, Yeonkyu Park

Forest of Bliss:

David Chonillo, Jorge Espinoza, Gigi Singh

Trans-Aggregation:

Donovan Dunkley, Saritza Martinez Rodriguez, Niomi Shah, Sofia Valdivieso

Four Commons:

Faisal Alzakari, Yue Hilary He, Ruilan Jia, Xiaohan Wang

IIT Student participants:

Dipanjan Nag, Nausad Ahmed, Anuradha Chakrabarti, Sunny Bansal, Thaju Zaman, Arpan Paul, Shivran Wattamwar, Vidhu Pandey, Aarsi Desai, Deepanjan Saha, Jyoti Kiran, Debanjan Kayal

Special Advisors:

Prof. Joy Sen, PhD, Prof. Arkopal K. Goswami, PhD, Prof. Bhargab Maitra (IIT), Students and Faculty of Banaras Hindu University

Curated and managed by:

Ban Edilbi, Jesse Hirakawa and Niharika Kannan

Copyright © 2018, The Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York. All Rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval, without permission from the publisher.