Introduction

Heritage Data and the Next Generation of Preservation Policy

Two generations ago, historic preservation secured its foothold in US public policy. The New York City Landmarks Law of 1965—a paragon of municipal preservation legislation—and the federal National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 codified a now widely accepted practice of government action to safeguard places of significance. The emergence of preservation policy infrastructure forged cultural conventions and encouraged public dialogue around heritage and its protection. It fostered and supported strong legal foundations and institutional arrangements—especially at the municipal level, where the power to regulate real property is greatest.

In those same two generations, the context in which preservation policy operates has shifted dramatically. World population has more than doubled, and it has become more urban. Today, most major metropolitan areas in the United States contend with growing and increasingly diverse populations. Urban built environments must accommodate this growth and at the same time meet multiple and often conflicting needs, including protecting open space and cultural resources, reducing energy and land consumption, adapting to climate change, promoting economic vitality, and ensuring social inclusion and community resilience.

These challenges place new demands on heritage preservation: it must demonstrate its value to society and the environment as it competes for political support and scarce financial resources within a complex urban agenda. In response, practitioners and academics are working to demonstrate the economic impacts of heritage protection, from increases in property values to job creation to tourism revenue. New research is also examining the environmental impacts of older buildings and neighborhoods and the affirmative role of existing (historic) structures in the ecological well-being of the planet. Empirical investigations into the role of arts and culture in communities shed additional light on the social value of heritage and the ways in which attachments to places are formed.1

Such research represents an important, though still very limited, reorientation of the preservation field toward evidence-based policy evaluation, particularly at the municipal level. Because preservation is often at odds with better financed and politically empowered real estate development interests, studies on the subject are often reactive and geared toward rationalizing investment in heritage by defending the status quo. Despite half a century of local policy experience behind us, there is still much to learn about the positive and negative influence of preservation on the social and physical fabric of cities. A better understanding of that influence can help policy meet contemporary needs more effectively and serve communities more justly.

Some may argue that such policy evaluation and the changes it may prompt constitute “mission creep” for preservation, which should instead focus on designating and regulating historic buildings and sites. Indeed, protection of the formal qualities of significant structures and districts forms the bulk of government-led preservation in cities across the United States. However, the policy rationales of most municipal ordinances, which provide the justification for investing tax-funded resources, reflect much broader mandates. Public education and welfare are certainly included within them, as are economic rationales such as generating tourism, stimulating growth, and increasing property values.2 These legal justifications fundamentally position preservation as a tool for enhancing quality of life and promoting community-building through the historic built environment.3 Revisiting that toolbox to improve its efficacy should be part of preservation’s remit.

The Urban Heritage, Sustainability, and Social Inclusion initiative—from which this volume developed—is a collaboration between the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, the Earth Institute–Center for Sustainable Urban Development, and the American Assembly, with support from the New York Community Trust. It seeks to build stronger linkages among researchers, policy makers, and practitioners in the heritage field by examining issues at the vanguard of urban preservation decision-making. Many government agencies dealing with preservation lack the mandate and the resources to independently explore emerging questions about policy, and the same is often true for not-for-profit and community groups. Though scholarly research on the topic is expanding, it remains fragmented. This initiative aims to counter that fragmentation and foster communication and collective action toward socially and environmentally responsive change. This new publication series, Issues in Preservation Policy, launches and makes public this exploratory discourse. The first question probed, and the subject of this initial volume, is the changing landscape of preservation-related data as an opportunity for, and foundation of, policy innovation. Two further volumes will discuss historic preservation’s relationship to social inclusion and new possibilities for assessing the outcomes of preservation policy.

Technological changes over the past decades have dramatically altered how we analyze and understand the built environment and communities. The existing preservation policy infrastructure was put in place before the advent of digital recording methods, the World Wide Web, and even personal computers. At its inception, it relied largely on visual and historical documentation to inform designation and the design review of formal changes to listed properties. Today, the increased accessibility of geospatial technology, open data laws, urban dashboards, the public engagement and multimedia options afforded by online platforms, and the burgeoning arena of civic tech engender a raft of quantitative and qualitative data, tools, and methods for understanding the relationships between people and their communities, and for informing policy decisions toward just and ecologically sustainable development.

This new data landscape presents a critical opportunity for preservation policy, as it is increasingly possible to analyze long-term effects and to consider criteria for success that are not currently included in decision-making frameworks. Evidence-based policy evaluation hinges on the capacity to forge, navigate, and build upon the potential of data in ways that are germane to preservation and its desired outcomes. The contributors to this volume explore this terrain in an effort to chart new paths of research and practice. Through the Urban Heritage and Data in the 21st Century symposium and the articles and interviews included in this book, a number of themes emerged that can inform the next generation of preservation policy.

THE POWER OF DATA COLLECTION AND MANAGEMENT

Information is a fundamental preservation policy tool. From the identification of what is heritage to documentation, promotion, and technical assistance, information enables collective action for public purpose and validates government decision-making and investment. It serves as a foundation for the application of other public policy tools, such as preservation regulation and incentives.4

At the core of government action are the lists or inventories that identify those places and resources worthy of public recognition and warranting some form of protection. As Lisa Ackerman notes, this impetus to classify heritage has a long history, and institutions as well as governments have pushed heritage data into the public arena. Some European governments began generating systematic lists of their historic monuments more than two centuries ago, and in 1931 the Athens Charter for the Restoration of Historic Monuments called for nation-states to create and publish heritage inventories.5 The importance of collecting and managing such heritage data persists as a policy priority: the top recommendation emerging from the Preserve America Summit, on the occasion of the fortieth anniversary of the National Historic Preservation Act, was to expand and increase the accessibility of heritage inventories.6

Such inventories take a range of forms, but increasingly, they capitalize on the geospatial technologies and software now readily available. Not only documenting but also mapping culturally or historically significant elements of the built environment is a powerful way to share information on the level of urban land use and planning, including for environmental review, zoning, transportation design, growth management, and disaster preparedness. Mapping likewise is an important medium for analyzing heritage in relation to demographics and other spatialized data.

Many municipalities are taking part in this new era of transparency as web-based platforms provide access to decades of existing—or legacy—data. The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission launched an interactive map, Discover New York City Landmarks, which provides detailed information about the city’s 1,400 individual landmarks, as well as 34,000 buildings within its 141 historic districts, culled from fifty years’ worth of designation reports and other research. This standardization of data allows for filtered searching, facilitates comparative analyses, and also provides a feedback portal for public input.7

The City of Los Angeles has taken the municipal heritage inventory even further. As Janet Hansen and Sara Delgadillo Cruz explain, the Historic Resources Office of the Department of City Planning has embarked on an ambitious program to document all of the city’s historic resources, designated and not designated alike. By first identifying important themes in Los Angeles history, or “historic contexts,” the city has been able to create an innovative public participation and mapping platform called SurveyLA to relate those themes to extant properties. The existing data on designated resources, as well as on those buildings identified through the survey, is all fully accessible and mappable in HistoricPlacesLA, the city’s online historic resources inventory and management system.

SurveyLA was an unprecedented effort in municipal heritage data collection, requiring significant human and financial resources, whereas the Discover New York City Landmarks project was an in-house operation on a limited budget. This difference is emblematic of the varying capacities of local governments and the range of data tools available. More sophisticated systems enable more complex spatial characterization and use analysis, allowing, for example, the inclusion of nonparcel resources (the street intersection where an important event occurred, viewsheds, and the like), the threading of sites into narratives, and the incorporation of older—not just designated—architecture and places. This enhanced functionality comes at a cost that may be beyond the reach of many municipalities. As Matthew Hampel emphasizes, from surveying and resurveying to updating data and software, collection and management of heritage information is an ongoing responsibility, not a onetime event (especially given the ever increasing roster of heritage sites). To sustain these systems, simplicity can sometimes be an advantage. Data collection and management, with clear goals in mind, should be internalized as part of the everyday operations of heritage agencies and institutions. Ultimately, these organizations need to focus on operationalizing data for social change.

DATA AS CIVIC ENGAGEMENT

Technological shifts in historic preservation over the last several decades have paralleled theoretical shifts in the field. Whereas heritage was traditionally viewed as having inherent value discernible only to experts, there is now an increased awareness of how society “creates” heritage by ascribing present-day values to places of the past. By valorizing particular styles, materials, people, events, narratives, and more, each generation influences the ways in which preservation policy is developed and implemented. Greater understanding of heritage as both a social process and a social construct has helped to foster broader public participation in decision-making about what to preserve and how.

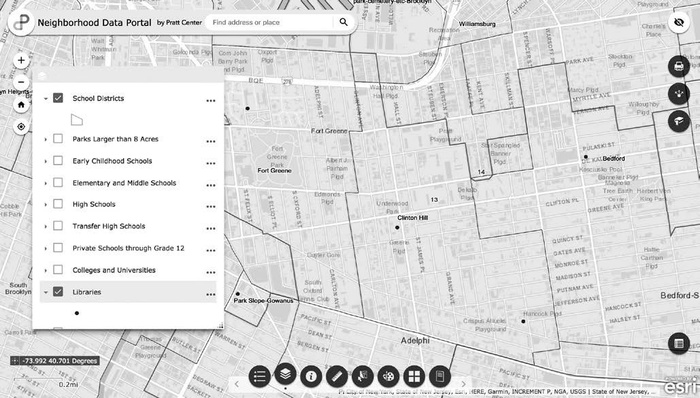

In the same way that significance is not objectively ascertained, data does not simply exist “out there” to be objectively collected and analyzed. The breadth of the new data landscape compels us to be vigilantly conscious of bias as we create and use information. It likewise obliges us to be mindful of who participates in surveys and data collection, analysis, and management and of the risks of exclusion. Empowering communities to access and use existing data as well as to co-create new data is thus a topic described by multiple contributors to this volume. Vicki Weiner, for example, describes the Pratt Center’s Neighborhood Data Portal as a tool to democratize information by making existing datasets about New York City’s built environment more easily accessible and usable. The goal is to empower diverse publics to improve their data literacy and, in doing so, to become more active participants in decision-making about their communities and built environments.

Several contributors underscore the notion of creating data with the public, not for it. Communities are makers, not just consumers, of data. Hampel speaks of data as a tactic of engagement: co- or self-designing surveys involve community members and help build collective buy-in. Whether data is for community asset mapping, collaborative visioning, or other forms of participatory planning, increasingly accessible tools and technology—from mobile apps to online public forums—can educate residents and empower them to explore and visualize data themselves. But Alicia Rouault contends that it is not (yet) common for municipal governments to work directly with communities in the production of official datasets. Universities and community-based organizations have a role to play: by helping to legitimize and integrate community voices in data-collection processes, they can facilitate (and instrumentalize) the co-creation of data.

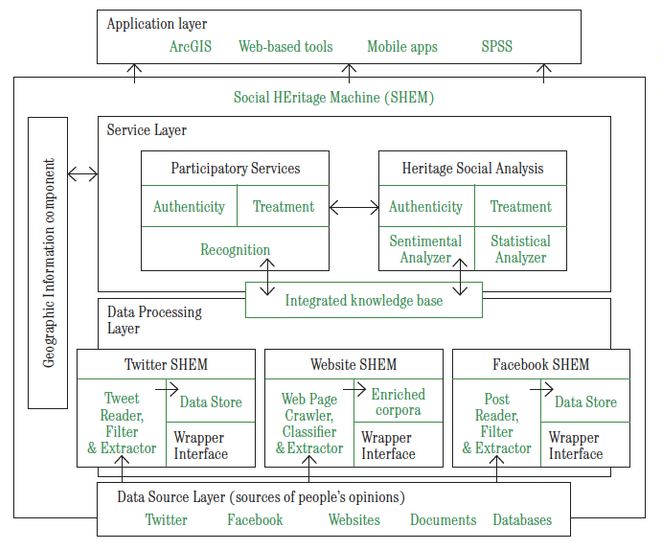

These ideas highlight the complicated relationship between expert and public ways of knowing when it comes to heritage. Preservationists bring disciplinary knowledge—and professional responsibility—to the heritage enterprise. At the same time, they are charged with helping to spatialize the narratives of diverse publics and realize community desires. These mandates are often in tension. As policy evolves and as participatory decision-making becomes more institutionalized, we may see a new generation of preservationists with expertise not only in heritage values (as defined by the field) but also in methods for better understanding how the public creates and values heritage. Jeremy C. Wells, Vanilson Burégio, and Rinaldo Lima explore how preservationists might develop new approaches to this charge. They propose a specialized web-based platform-cum-computational tool, the Social HEritage Machine (SHEM), to collect metadata on the language laypeople use to relate to heritage. A better understanding of public perceptions can help make heritage decision-making more responsive to community interests and help reconcile public and expert knowledge.

However, Eduardo Rojas reminds us that while data may be increasingly democratized, the decision-making processes they inform may not be. Different social actors have varying degrees of agency and leverage in preservation policy. In generically categorizing “communities” or “the public,” we sacrifice a more nuanced understanding of these diverse stakeholders (whether individuals or institutions) and the relative influence each brings to the table. More than simply understanding public perceptions, we also need to understand who has power in decisions that affect heritage, what their motivations are, and how the creation and use of data may influence these dynamics. In this sense, it is important to remember that the new data landscape and civic engagement are not only about big data. Rouault outlines several tools that are helping to gather individualized, qualitative data. Marco Castro Cosio illustrates the importance of intimate, personal knowledge through his work incorporating visitor memories at the Queens Museum and taking community engagement beyond the walls of cultural institutions.

BUILDING PRESERVATION POLICY-SPECIFIC DATA

Preservation has a long legacy of deep qualitative research into the formal arrangements and historical meaning of significant places. The new data landscape in many respects affords the possibility of transectional views of preservation policy decisions, across time and space and between people and places. But standardizing and scaling data to foster such views can, at times, be at odds with traditional heritage research methods and discipline-specific forms of data. Likewise, inaccuracies in existing data and disparate data types complicate both cross-sectional and longitudinal research. Andrew S. Dolkart raises the issue of bad legacy data, using “year built” information from New York City’s PLUTO database as an example of how a single datum fails to represent or capture the relevance of time and longitudinal change. Amanda L. Webb likewise plumbs the “year built” polemic, arguing that date of construction can be a seminal piece of information for preservation decision-making but that it is nevertheless nonstatic and inexact.

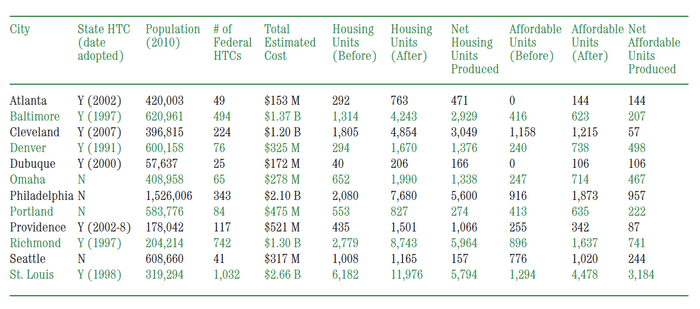

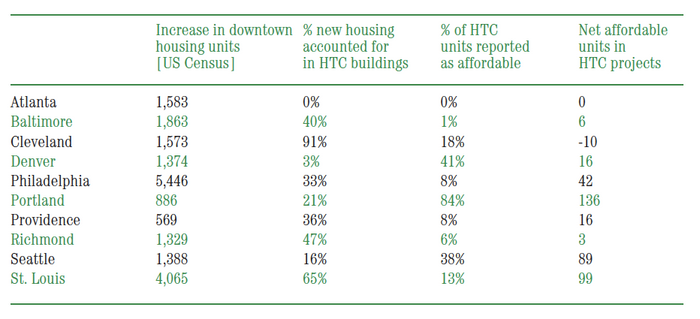

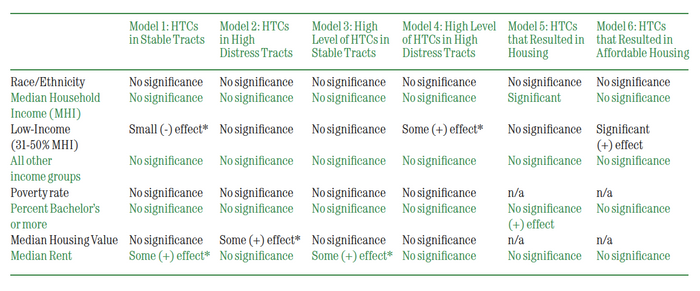

Threaded throughout the volume is a call to collect, characterize, and manage data in ways that more effectively serve the preservation enterprise. Despite its long history of creating and managing inventories, and more than half a century of policy implementation in the United States, the preservation field has a poor track record of systematizing data. Stephanie Ryberg-Webster and Kelly L. Kinahan, in their research on federal historic tax credits, and Michael Powe, in his work with the National Trust’s Research and Policy Lab, highlight the lack of baseline policy data, mismatched data repositories, and variable data quality endemic to preservation. These shortcomings impede robust policy research and underscore the fundamental role that government must play in ensuring effective data collection and management.

Douglas S. Noonan and Tetsuharu Oba argue that a great promise of new technology is the opportunities for “connecting previously disconnected datasets.” And preservationists need not carry that burden alone. Rouault, Hampel, and other technology experts who have participated in this dialogue stressed the passion in the tech world for tackling these types of problems. Engaging “civic hacker types” and drawing on the ever-improving means of data collection—from crowdsourcing to crowd editing to data scraping—can open up new possibilities for preservation policy research. That said, there is still an essential role for what Rouault refers to as “translators,” those with both tech knowledge and an understanding of the built environment and urban planning tools, who can mediate between these fields, help to optimize data, and spearhead research that is preservation policy-specific. Jennifer L. Most echoes this idea; she argues for better training of preservationists in GIS and other data-driven research methods and for empowering preservationists to work with quantitative data. There is an inextricable link between evidentiary data and the stories we seek to tell as preservationists; therefore, preservationists must be educated and professionally positioned to analyze their own data and to evaluate the outcomes of their own policies. While interdisciplinary collaboration may be warranted, the preservation community also needs its own data fluency to ensure that the preservation-specific data and policy research needs of the field are effectively addressed.

CHALLENGING AND SUBSTANTIATING NARRATIVES

In the same way that legacy data can complicate contemporary research, there are legacy narratives that influence the discourse surrounding preservation policy and its effectiveness. Randall Mason argues that the new data landscape affords possibilities for new discoveries, new stories, and new connections. It may likewise challenge preservation’s ways of knowing and doing by testing longstanding narratives. For example, the aforementioned SHEM platform specifically seeks to challenge expert knowledge—the “authorized heritage discourse”—by experimenting with new methods for probing public values and perceptions. Castro Cosio’s work in interactive technologies supports community and individual storytelling, reinforcing the idea that heritage is more than just a set of resources to be preserved: it is also an open-ended, spatialized narrative of collective memory.

Heritage narratives relate not only to what and how we preserve but also to why we preserve. Emily Talen, through her study of mom-and-pop retail, and Powe, through his work showing why old buildings matter, analyze and find evidentiary support for a fundamental tenet of preservation first proffered by Jane Jacobs: that neighborhoods with a mix of old and new buildings have a positive influence on urban vitality. Both caution that the potential of such research can only be realized if there is a clear articulation of the ways in which preservation policy goals intersect with socioeconomic goals, such as supporting small businesses. Preservation policy’s emphasis on regulating historic fabric cannot, in and of itself, plumb the dynamics of these social-spatial relationships, nor can it assure outcomes that engender broader social and economic benefits.

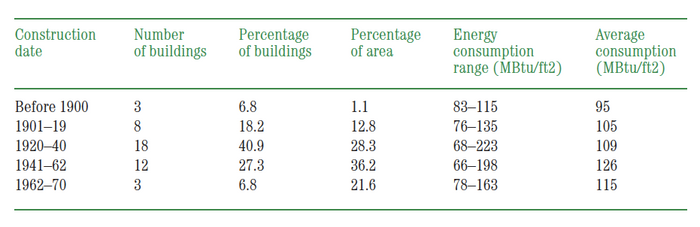

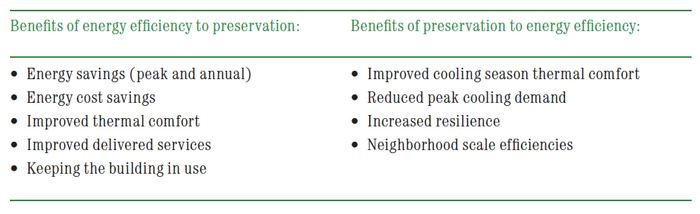

Similarly, climate change has given new voice to a preservation narrative dating back to the oil crisis of the 1970s, which asserts that old buildings are inherently more energy efficient. Webb makes a strong case for how increasingly sophisticated energy data and research may not support this claim. However, because policy research in the realm of preservation is often advocacy driven, it may focus too heavily on reinforcing the time-honored narratives. The energy narrative is underpinned by a preservation philosophy that strives to minimize physical change, and adherence to it misses the opportunity to maximize the potential benefits of energy efficiency in the historic built environment. More explicitly aligning the goals of energy efficiency and historic preservation could inform more sustainable heritage policies, and new energy data provides a rich foundation for exploring these intersections. In this sense, the field can operationalize data to evolve preservation narratives and update policies in response to contemporary needs.

INFORMED DECISION-MAKING AND EVIDENCE-BUILDING

The primary tool in the municipal-level preservation policy toolbox has historically been the regulatory instrument of designation. The use of government action to physically protect a historic property from market forces and the specter of significant physical change—or the lack of such protection—has institutionalized a binary mind-set. One might argue that the overreliance on this one powerful tool has inhibited the development of other policy instruments that more deeply explore the broad spectrum of options between “saved” and “not saved.”

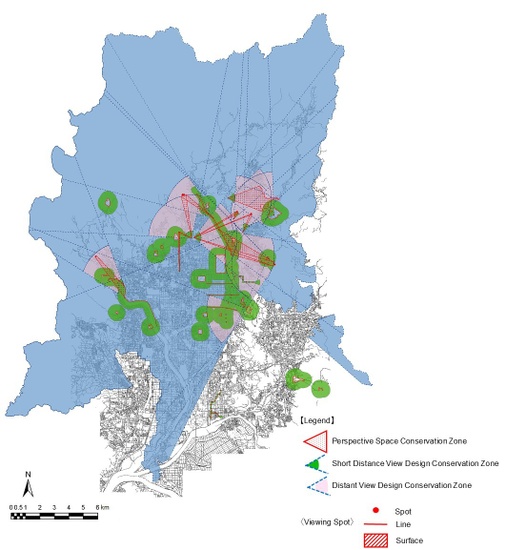

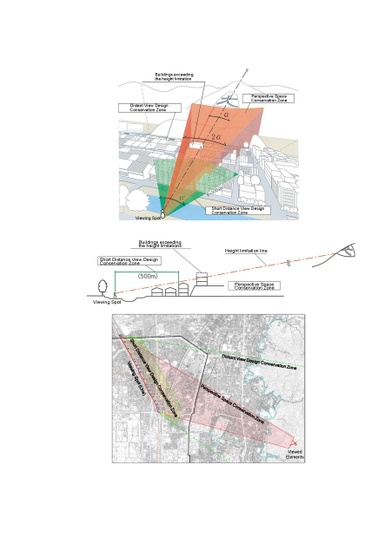

Data in service of policy can provide critical feedback loops and insight into new avenues of policy development or governance reform. In their analysis of Kyoto, where datasets track the implementation of landscape and viewshed policy, Noonan and Oba argue that this kind of monitoring informs decisions about Kyoto’s wider heritage resource portfolio and advances the “menu of policy tools.” Hansen and Delgadillo Cruz emphasize that HistoricPlacesLA enables better management of heritage resources but also facilitates the integration of heritage interests within broader planning and land use decisions. Powe reaffirms the power of data to inform urban policy, especially when aggregated and evaluated across municipalities. Even beyond policy, both Ackerman and Mason underscore the potential of data to improve heritage management and governance structures and to connect preservation more substantively with other disciplines. Heritage data can help forge the channels needed for cross-policy research, interagency cooperation, and decision-making systems for the built environment and for communities. It can likewise unite governmental policy actors through mutual accountability.

Data, as Hampel maintains, imparts legitimacy and gets preservation a proverbial seat at the table. It is not only a building block of policy research; it is also a form of political currency. Data can leverage support and resources, build trust, speak truth to power, and engage “opponents” to negotiate solutions. But capitalizing on this potential requires preservation to actively engage in other urban agendas and embrace policy outcomes beyond the protection of architectural fabric. Economic vitality, social well-being, and environmental sustainability are all areas in which preservation claims a role, though largely to support the existing priorities of regulatory designation and design review. The new data landscape calls on the field to build a more evidence-based cadre of data and research that does not simply use these claims to justify its cause but instead thinks creatively and progressively about improving its policies in relation to the results they produce.

On the economic front, Main Street and small-business interests, as Talen suggests, constitute an area of common ground. Rojas sees untapped opportunities for preservation policy in urban investment and more holistic decision-making. Ryberg-Webster and Kinahan underscore how improved data can help us understand the role of incentive-based policy tools, like historic tax credits, and better position preservation to align with urban revitalization agendas. The environmental front offers a lot of low-hanging fruit with regard to data and research. By acknowledging energy efficiency as a means to preserve, rather than as a threat to historic fabric, Webb argues that research into better models and benchmarking could enhance the stewardship of heritage as an integral element of a sustainable built environment.

TELLING BETTER STORIES, ASKING BETTER QUESTIONS

Will better data lead to better preservation? The rosters of heritage sites in the United States and around the world are growing. But quantity does not necessarily equate to quality. As a form of public policy, intended to serve all, there is an obligation on the part of preservation to tell better stories through the historic built environment—stories that represent the diversity of our communities, stories that redress spatial and social inequities, and stories that reflect our collective agency in promoting a sustainable environment. But to tell better stories, preservation must ask better questions.

Asking better questions means taking stock of the last half century of preservation policy implementation. It entails establishing a culture of self-reflection that counterbalances the impulse to keep identifying more and more heritage by critically evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of our work vis-à-vis society and the environment. Asking better questions also involves recasting preservation as a means of instrumentalizing heritage to align with and support related urban goals, rather than to serve as an end in and of itself. It means more evidence-based research that works toward socially inclusive processes, which in turn support a just and sustainable built environment, all to inform the next generation of preservation policy.

The new data landscape is fraught with challenges, and preservation’s existing data deficiencies and limited policy-research infrastructure only compound these problems. But the opportunities for improved heritage management and policy reassessment far outweigh the potential difficulties. A new outlook on and orientation toward data can help modernize the preservation policy toolbox and enhance the benefits that heritage can create for society.

See appendices for a literature review examining these research avenues.

Erica Avrami, Cherie-Nicole Leo, and Alberto Sanchez-Sanchez, “Confronting Exclusion: Redefining the Intended Outcomes of Historic Preservation,” Change Over Time 8, no. 1 (forthcoming).

Carol M. Rose, “Preservation and Community: New Directions in the Law of Historic Preservation,” Stanford Law Review 33, no. 3 (February 1981): 473–534.

J. Mark Schuster, “Information as a Tool of Preservation Action,” in Preserving the Built Heritage: Tools for Implementation, ed. J. Mark Schuster, John de Monchaux, and Charles A. Riley II (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1997), 100–123; J. Mark Schuster, “Making a List and Checking It Twice: Information as a Tool for Historic Preservation,” Cultural Policy Center at the University of Chicago, November 25, 2002.

Stefan Fisch, “National Approaches to the Administration of Historical Heritage,” in National Approaches to the Governance of Historical Heritage Over Time: A Comparative Report, ed. Stefan Fisch (Amsterdam: IOS Press, 2008), 1–13; “First International Congress of Architects and Technicians of Historic Monuments, 1931,” Athens Charter for the Restoration of Historic Monuments.

Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, The Preserve America Summit Executive Summary: Charting a Future Course for the National Historic Preservation Program (Washington, DC: ACHP, 2007).

Meenakshi Srinivasan, Lisa Kersavage, and Daniel Watts, “NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission’s Historic Building Data Project” (PowerPoint presentation, Urban Heritage and Data in the 21st Century Symposium, New York, NY, February 8, 2018).

Institutionalizing Data

1

Big City, Big Data: Los Angeles’s Historic Resources

When most people think of Los Angeles, historic preservation does not come to mind. But Los Angeles’s 1962 Cultural Heritage Ordinance, which established a program for the local designation of city monuments, makes the city’s historic preservation program one of the oldest in the country—predating both the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) and the founding of the National Register of Historic Places. More recently, Los Angeles has been at the national forefront in its efforts to provide a comprehensive and up-to-date record of the city’s important historic resources. The resultant dataset—the largest publicly accessible digital dataset on significant historic resources of any city in the nation—is the product of two parallel but related projects: SurveyLA and HistoricPlacesLA. SurveyLA, the citywide historic resources survey, was specifically designed to identify and document important resources in Los Angeles that are not designated under any local, state, or federal program and that cover a broad range of historic and cultural themes and property types. HistoricPlacesLA, the city’s online historic resources inventory and management system, grew out of the need to keep data on all of the city’s historic resources, including those documented through current and future survey work and designated properties, in a single location where it is fully accessible, mappable, and searchable.

DOCUMENTING HISTORIC RESOURCES

In US cities large and small, there is a resurgence of interest in completing historic resources surveys, particularly at the citywide level. Some municipalities are updating and augmenting existing surveys, while others are pursuing surveys for the first time. Most survey work in American cities started in the late 1970s and the 1980s. After the passage of the NHPA in 1966, the National Park Service developed professional standards and guidelines for surveys including the 1977 Guidelines for Local Surveys: A Basis for Preservation Planning (revised in 1985) and the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards and Guidelines for Archaeology and Historic Preservation (published in 1983 and since revised). These publications provide technical advice regarding the identification, evaluation, and registration of significant historic resources as well as a framework for using this information to inform preservation planning. Although more than thirty years old, these publications still serve as go-to sources for standards.

The NHPA also called for the establishment of state agencies to implement provisions of the law, including statewide surveys of historic resources. State preservation programs developed survey standards based on the federal standards. By the 1970s, a growing interest in municipal preservation programs led to the 1980 amendment of the NHPA, which established the Certified Local Government (CLG) program to offer federal grant funding for surveys and to encourage local government participation in the identification and preservation of historic properties in their jurisdictions. Early municipal survey work from this time generally focused on buildings of architectural significance and typically covered only resources dating from before World War II.

The information needed to complete standardized historic resource survey forms drove data-collection processes for early surveys. While some municipal agencies designed forms in-house at this time, state preservation agencies developed forms for statewide use. In either case, the forms were completed from handwritten field notes—first in hard copy and later as digital forms filled out on a computer. The reliance on paper forms limited thinking about the kinds of data that could be collected and what could be useful for planning and other purposes. Though some state and local agencies put survey data into a simple database to allow for rudimentary sorting and searching, in most instances these survey forms were shelved. Nevertheless, the result in Los Angeles, as elsewhere, is that this legacy data, available in a variety of digital and nondigital formats, often serves as the starting point for new surveys.

The reasons for the renewed interest in survey work are varied but are connected to technological advances that make data collection more efficient and economically feasible and that also make the data more usable. Urban centers such as Los Angeles are experiencing fast-paced growth, as well as pressure to create more housing, revitalize neighborhoods and downtowns, develop transit-oriented communities, and embrace diversity, all while dealing with issues including gentrification, displacement, and economic inequality. Usable information on historic resources is critical to meeting community objectives in planning for growth and change. New technologies allow for the collection of precise spatial data, the recording of a wider range of resource types, the incorporation of digital photography, and the inclusion of historic contexts, all of which contribute to an analytical framework for using the data to inform planning goals and policies.

Contemporary surveys also expand on the time frame covered to include postwar resources, which now make up a large percentage of the built environment in American cities. These surveys focus on associated topics including midcentury modern architecture, postwar suburbanization, and even the more recent past. Similarly, the field of preservation generally is experiencing a shift in terms of social inclusion and the identification and celebration of diverse places of ethnic, social, and cultural importance, which have been largely underrepresented in earlier surveys and historic preservation efforts. Along with this shift, the field encourages innovative outreach strategies to include all communities in historic preservation, especially as community members are expert sources of information on places that matter. These factors broaden the meaning of the term “historic resource” to now include resources not represented by earlier surveys. This shift in focus is concurrent with the now common use of more fluid terms such as “cultural resource” or “heritage resource.”

DOCUMENTING HISTORIC RESOURCES IN LOS ANGELES

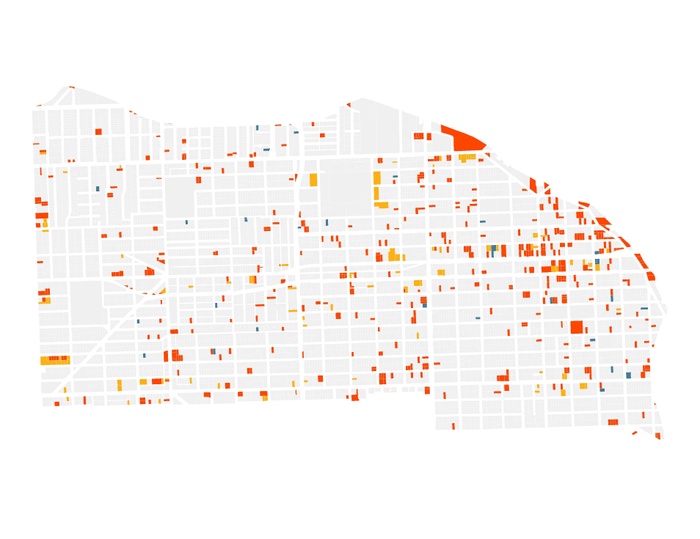

The concept of a citywide historic resources survey and inventory for Los Angeles started in 2000 when the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) undertook a study of the potential for a documentation effort of this magnitude—Los Angeles encompasses about 500 square miles and includes 880,000 legal parcels. FIG. 1. The GCI’s Los Angeles Historic Resource Survey Assessment Project: Summary Report (2001) revealed that only 15 percent of the city had previously been surveyed and that city government, neighborhoods, preservationists, and the business community supported the need for reliable and up-to-date information on the city’s historic resources.

FIG. 1: The expansive city of Los Angeles, as seen from the Griffith Observatory. Image: Asim Bharwani/Moment/Getty Images.

In 2005 the city entered into a multiyear grant agreement with the J. Paul Getty Foundation to complete the citywide survey.1 SurveyLA, as it came to be called, officially launched in 2006 with the establishment of the city’s Office of Historic Resources (OHR) to manage the project. The inception phase relied heavily on the GCI’s publication The Los Angeles Historic Resource Survey Report (2008), which provided a blueprint for the project and addressed such issues as technology, historic contexts, public engagement, use, dissemination, and long-term management of the resulting data.

SurveyLA is not the first large-scale survey of Los Angeles. Efforts to initiate a citywide survey began in the late 1960s, not long after the adoption of the Cultural Heritage Ordinance and establishment of the Historic-Cultural Monument designation program.2 With the passage of the NHPA came the implementation of the National Register of Historic Places and the associated federal Section 106 review process. City agencies receiving federal funds for projects and responsible for Section 106 review included the Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) and the Bureau of Engineering (BOE). While the CRA began conducting small-scale surveys in areas under their jurisdiction, the Cultural Heritage Commission and BOE worked together to find funding for a citywide survey. The California Office of Historic Preservation (established in 1975) awarded Los Angeles a grant in 1979 to plan a survey and another grant in 1980 to implement it. While at the time it was referred to as a citywide survey, the project focused on a limited number of areas; after all, with a general fifty-year rule for National Register eligibility, the survey considered only resources dating from before 1930 and did not include the vast sections of Los Angeles largely developed after World War II, including the San Fernando Valley.3 Twenty-five years later, plans for a citywide survey broadened to include all of Los Angeles and to cover the period up to 1980.4

DEVELOPING A METHODOLOGY FOR SURVEYLA

In this new era of survey work, Los Angeles was the first city in the nation to complete a citywide survey using digital technology. From its inception, the project followed best practices in historic preservation, including standards and guidelines developed by the California Office of Historic Preservation and the NPS. However, the project updated these practices to take advantage of new technologies and to fully digitize the data-collection process. Factors taken into account included the level and type of documentation required to satisfy the standards of the state survey forms, to provide the foundation for a comprehensive preservation program, and to serve as baseline data for planning purposes. Developing strategies for public participation in the survey came later.

The sheer geographic scale of the survey required some basic decisions about what resources would be recorded and how. Efficiencies of scale demanded that a new approach be applied to what is known as an intensive level survey, where in-depth research is conducted on every property in a survey area and the recording process includes detailed, narrative descriptions and significance statements. To do so in Los Angeles would have taken decades. The new methodology implemented efficiencies to accomplish the following:

Efficiencies in field survey work were also achieved through the use of a customized geographic information system (GIS) survey application loaded on portable tablet computers.5 FIG. 2. At the time SurveyLA pilot surveys began in 2008, no off-the-shelf software for historic resources data collection was available.6 Most municipalities and agencies developed their own in-house systems, using simple databases and spreadsheets, as GIS software for historic resource surveys was in a nascent stage. To take advantage of the most updated technologies, city planning staff worked with consultants to develop SurveyLA’s survey application with the ability to do the following:

Ultimately, the structure and content of the field application contributed to the consistency and quality of the data collected, and the GIS platform visualized this fully searchable dataset on a map. The ability to accurately map the data offered a great advantage over the creation of a customized, nongeographic database for the storage and long-term use of the resulting dataset.

Digitizing Historic Contexts

Standard No. 1 of the “Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Preservation Planning” is “Preservation Planning Establishes Historic Contexts.” As stated in the standard:

Decisions about the identification, evaluation, registration, and treatment of historic properties are most reliably made when the relationship of individual properties to other similar properties is understood. Information about historic properties representing aspects of history, architecture, archeology, engineering, and culture must be collected and organized to define these relationships. This organizational framework is called a “historic context.” The historic context organizes information based on a cultural theme and its geographical and chronological limits. Contexts describe the significant broad patterns of development in an area that may be represented by historic properties. The development of historic contexts is the foundation for decisions about identification, evaluation, registration, and treatment of historic properties.7

FIG. 2: Portable tablet computers expedite the surveying process. Image courtesy of the City of Los Angeles, Department of City Planning.

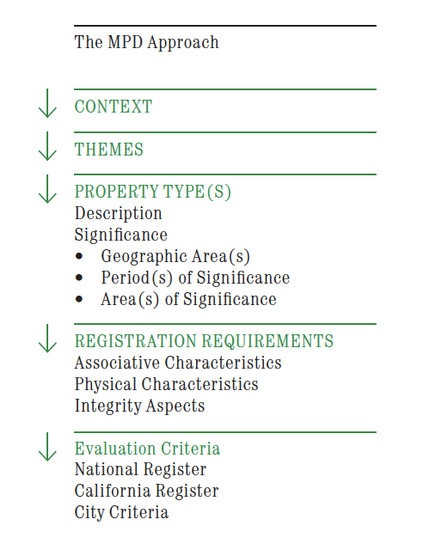

FIG. 3: Diagram illustrating the Multiple Property Documentation approach applied in SurveyLA field surveys.

A historic context statement is a narrative, technical document that guides the survey and evaluation of historic resources. Historic contexts differ from other types of narrative histories in that they identify important themes in history and then relate those themes to extant historic resources or associated property types. Historic contexts establish the significance of themes and related topics and provide specific guidance regarding the physical and associative characteristics necessary to be a good example of a type. While narrative contexts have served as the foundation for best survey practice for decades, new technologies enable the development of contexts in digital formats to collect and use significance information in meaningful ways. Further, contexts—and survey work generally—have moved away from an emphasis on architectural significance to cover a broader range of topics, especially ethnic, gender, and cultural histories.

Los Angeles’s citywide historic context statement (HCS), initiated as part of SurveyLA, is based on the Multiple Property Documentation (MPD) approach developed by the NPS. FIG. 3. This approach organizes the trends and patterns of history shared by properties into themes, identifies and describes property types that represent those themes, and provides registration requirements to guide evaluation. Evaluating properties on a comparative basis within a given geographical area can help establish preservation priorities.

Although the intent of the MPD format is to streamline the nomination of properties related by theme to the National Register, it is also highly effective for survey work at any level. The format clearly defines the structure and content of contexts and establishes a narrative statement of significance applicable to all related property types. The registration requirements detail the physical and associative characteristics and integrity aspects a resource must have to be a good example of a type, making them usable for the National Register as well as local and state registration programs.8 Importantly, the MPD format provides a consistent evaluation framework for use by all field surveyors and eliminates the need for customized narrative significance statements for every property surveyed.

SurveyLA’s HCS is organized into nine broad contexts, listed below, which cover the period from about 1780 to 1980 and are specific to the city of Los Angeles.9

The contexts are further refined into a number of themes, over two hundred in all, associated with the architectural, social, ethnic, and cultural history of Los Angeles; the themes cover a wide range of topics and associated property types, such as Automobile Suburbanization, Water and Power, Labor History, Aviation and Aerospace, Los Angeles and the Automobile, and Women’s Rights. The city has also developed themes relating to the histories of the LGBT, Jewish, Latino, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Thai, Filipino, and African American communities of Los Angeles.

While the narrative historic contexts stand alone, the property types and evaluation components of the HCS have been formatted as drop-down lists during data collection. This format is highly replicable for survey work carried out by any agency at any scale and provides an analytical framework for studying survey results. Since context information is collected electronically, it gives immediate information on the citywide geographic distribution of property types by theme and by frequency, abundance, or rarity of a resource; it streamlines the evaluation of resources in accordance with national, state, and local designation criteria. Los Angeles’s HCS is now being used by city and outside agencies so that all surveyors are using the same evaluation framework. Because the HCS format follows federal standards, it is usable by any US municipality conducting context-based surveys. The concept is even gaining interest worldwide.

Incorporating Community Outreach into Data Collection

Engaging the public in the process of data collection is critical to all survey work. For SurveyLA, the city developed a comprehensive outreach program that included various components.10 Throughout SurveyLA, outreach focused on developing multilingual materials, reaching out to underrepresented communities, and broadening the public’s concept of preservation beyond the protection of architecturally significant buildings. The program evolved over a number of years based on feedback from the public, lessons learned, and available funding. Ultimately, one of the main objectives of outreach was to directly engage the public in helping identify places of significance in communities throughout Los Angeles.11 Particularly important were places whose social, ethnic, and cultural significance were not readily known from field surveys alone. This section focuses on components of the outreach program that directly informed the data-collection process.

Members of a public outreach advisory committee, organized early on for SurveyLA, underscored the need to help the public understand what type of information was valuable to SurveyLA and in what format it should be submitted. From this input, the OHR and a consultant team developed the MyHistoricLA program, which included three components. The MyHistoricLA questionnaire, a form with a series of ten short questions, was widely distributed in hard copy at outreach meetings, public libraries, city council offices, and other places.12 The SurveyLA website also featured a form that could be submitted directly to the OHR.

The associated Guide to Public Participation in SurveyLA went further to collect information at a neighborhood level. A previous version of the guide explained:

There are a million stories in the “City of the Angels,” and MyHistoricLA wants to know yours. Help us reveal the history of the people and places that make Los Angeles unique. Where do you live? What do you know about who lived there before you? How has your neighborhood grown or changed? What is your favorite historic building in your neighborhood or area? MyHistoricLA seeks to uncover the varied and multicultural heritage of the city, engage residents neighborhood by neighborhood, identify traditionally underrepresented groups, and gather information about resources of social and cultural significance.13

Activities in the guide have been divided into themes to collect a wide range of historic information and insight; the guide includes a variety of activities to engage both individuals and groups.

The MyHistoricLA form allowed neighborhoods to take ownership of and manage their own contributions to SurveyLA, and the companion guide offered information up front, to inform surveys before fieldwork started. To make this method possible, the OHR designed a spreadsheet that indicated the type of data collected for SurveyLA and the associated data fields in the survey application. The OHR, primarily working with graduate student interns, undertook a large-scale effort to collect outreach information into GIS data for use during field surveys. For example, standing in front of an otherwise undistinguished single-family residence, a surveyor could quickly access the story of an important person who lived there.

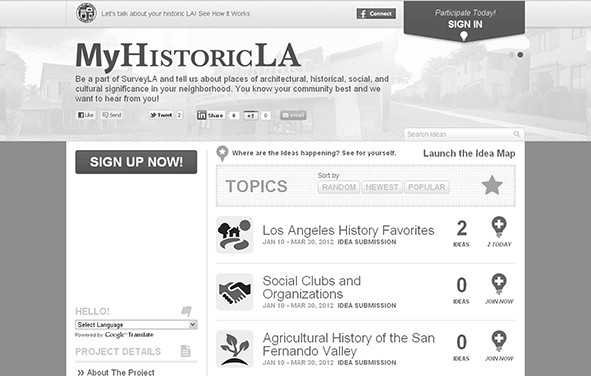

While the form and the guide resulted in useful information, in reality this success was limited. In-person training meetings for the guide were generally not well attended, and the OHR had no dedicated staff and limited funding for outreach. The MyHistoricLA website (MyHistoricLA.org), launched in 2012, grew out of a need for public engagement with a broad-based audience and a desire to initiate online conversations. The OHR implemented MyHistoricLA during field surveys rather than ahead of them. As with the form and the guide, the website allowed a diverse audience of participants to provide information on historic resources. It also allowed the OHR to pose questions about resources in specific geographic areas to fill information gaps. For example, while surveying in the suburbs of the San Fernando Valley, MyHistoricLA asked participants about the now rare agricultural resources that remain, which may not be readily visible from the public right-of-way. FIG. 4.

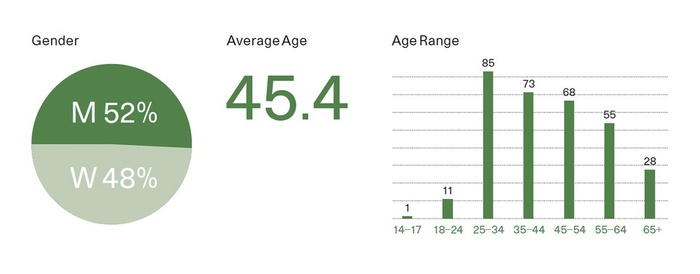

A feature of the system tracked demographic information on participants. FIG 5. The MyHistoricLA website was short-lived because of its limited success in reaching all of its intended audiences. However, it is nevertheless helping to shape future plans to reinstate an online and ongoing forum for public participation.

FIG. 4: The MyHistoricLA web page.

FIG. 5: Gender and age of MyHistoricLA users. Courtesy of the City of Los Angeles, Department of City Planning.

SHIFTING MIND-SETS AND THE RECORDING OF RESOURCES

Local efforts to identify places that matter in Los Angeles mirror national efforts to be more inclusive in the type of resources recorded and to develop programs that reflect the country’s diverse communities. The shift in the way resources are recorded and the reasons resources should be considered important are underscored by SurveyLA’s methodology. Guiding survey work with historic contexts leads to identifying and recording a wider range of property types than had been considered in earlier surveys.14 Information received through outreach efforts greatly informed contexts and surveys associated with social, ethnic, and cultural significance. These associated property types and resources may have gone unnoticed without the community’s input. Sites representing cultural histories and unique property types raise questions about how these places are taken into account in survey work and, more importantly, in the development of planning policies for the communities that value them.

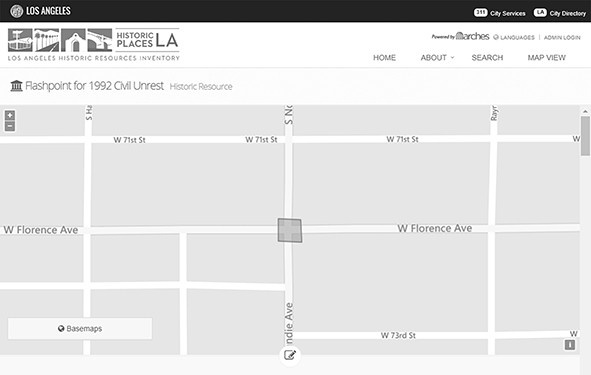

One example is a street intersection significant for its association with the events of Los Angeles’s 1992 uprising. FIG. 6. The intersection is a flashpoint site and the location of the beating of Reginald Denny following the acquittal of police officers tried in the Rodney King case.15 Despite the fact that no more than twenty years had passed, SurveyLA recorded this site based on a context-driven approach, rather than recording only resources that met the fifty-year age requirement established by the National Register.16

FIG. 6: Image of the intersection of Normandie and Florence Avenues, a flashpoint of the 1992 civil unrest in Los Angeles. Image courtesy of the City of Los Angeles, Department of City Planning.

DEVELOPMENT OF HISTORICPLACESLA

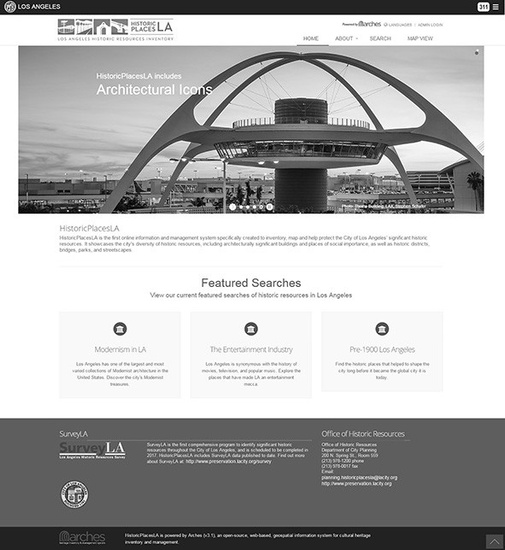

To accomplish the goal of improving access to historic resources data in Los Angeles, the city and the GCI further built upon the SurveyLA partnership. As SurveyLA field surveys progressed, the GCI and World Monuments Fund (WMF) had separately been developing Arches, an open-source, geospatial, and web-based software, to document and inventory cultural heritage sites worldwide.17 The GCI chose Los Angeles as the first large-scale US implementation site for Arches. This customized system, named HistoricPlacesLA, premiered in 2015.18

FIG. 7: Home page for HistoricPlacesLA.

The Arches software was created in response to the substantial challenges in data management faced by heritage organizations globally. Recognizing the lack of software systems to address these challenges, the GCI and WMF set out to provide a user-friendly, low-cost, and accessible solution. The collection of heritage data often involves many different digital and nondigital formats, and datasets vary widely in both scale and complexity. Many organizations and communities that are engaged in protecting some of the world’s most threatened heritage resources do not have access to sophisticated technology or substantial funding. Nevertheless, as in the case of Los Angeles and most heritage-based organizations, making relevant data easily accessible is a high priority.

First released for public use in 2013, Arches is a web-based inventory and management platform with GIS capabilities created specifically for cultural heritage data. Because Arches is open-source, heritage organizations worldwide can independently deploy and customize the system to fit the resources they manage while also meeting widely adopted international standards for heritage-resource inventories. FIG. 7.

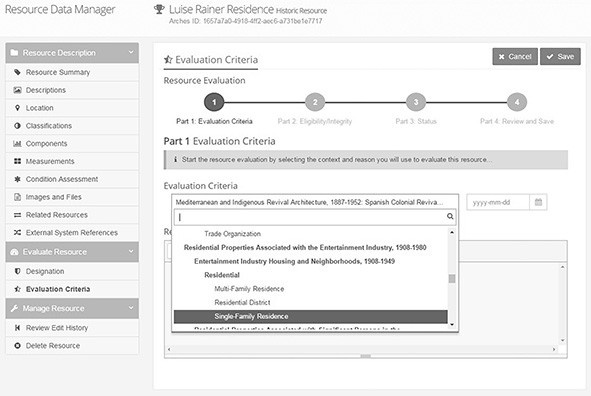

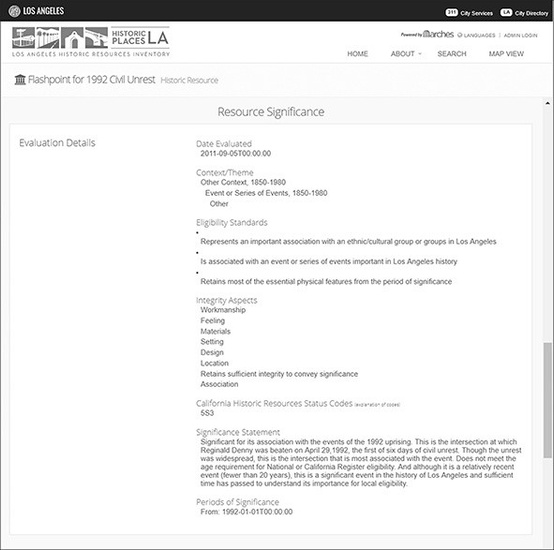

The use of international standards for information technology, heritage inventories, and heritage data management by Arches promotes data sharing; meanwhile, the format in which the data is stored safeguards its longevity.19 For HistoricPlacesLA, Arches’s carefully developed structure is merged with the federal- and state-standards framework of SurveyLA to support the data for surveyed and designated historic resources within the boundaries of the city. FIG. 8.20 As an online searchable database, HistoricPlacesLA is a valuable resource for the city and the public to conduct advanced queries using mapping, geographical buffers, time frames, and even combined searches. FIG. 9.

FIG. 8: Adding or editing a resource in HistoricPlacesLA is steered by the Multiple Property Documentation approach.

FIG. 9: Map of the intersection of Normandie and Florence Avenues. The resource was recorded as a polygon, encompassing the site.

BIG DATA: WHAT’S IT FOR?

With big data comes big responsibility. Los Angeles now has the largest and most advanced dataset on historic resources of any municipality in the United States. This puts the city at the forefront of a new era in digital historic resources data, which can serve a range of purposes both within and outside urban planning. While on its own the dataset is impressive, it becomes more powerful when integrated into HistoricPlacesLA. At the most basic level, HistoricPlacesLA serves as a system to manage information on historic resources over time. FIG. 10. But this information has broader uses: it can both inform and influence the shifting practice of historic preservation in Los Angeles and in the United States more widely.

The city’s responsibilities lie not only in managing and maintaining the data but also in promoting its use. As the first step in this process, the Department of City Planning hired a data manager, signaling its long-term commitment to HistoricPlacesLA and making historic resources data available. The ultimate goal is to have HistoricPlacesLA serve as the one-stop source of information for the city’s significant historic resources.21 With SurveyLA now complete, work is underway in the OHR to fully integrate the data into HistoricPlacesLA. As well, data integration includes adding further survey data, revising and expanding the historic context statement, and providing up-to-date and complete records of the city’s designated historic resources.22 While this data integration continues, new features for Arches are in development. Most notable is the forthcoming mobile data-collection, which allows for the remote addition of new survey records, both small and large, directly into the system, eliminating the need for data conversion. When this feature is implemented, HistoricPlacesLA will be a single system to collect, manage, use, and query data.

FIG. 10: Evaluation and significance of the site associated with the 1992 civil unrest in Los Angeles, as seen in HistoricPlacesLA.

The OHR also plans to add capabilities that facilitate administration of the city’s historic preservation programs, in parallel with the development of the casework/workflow module in development for Arches. For the city, this feature could provide a much-needed system to track processes associated with formal historic designation and financial incentive programs. In addition, because it is an open-source platform, improvements to the Arches software will become available to other heritage organizations as they implement and customize Arches for their use. The city will benefit from contributions made by other organizations in the Arches open-source community.

Opportunities for the dataset are still evolving and will accelerate as data integration into HistoricPlacesLA is completed. Consistent with the earlier goals and objectives of SurveyLA, uses of the data now focus largely on shaping preservation planning in Los Angeles. The Department of City Planning is, in fact, the primary user of the data. Most often, the data informs day-to-day case processing and decision-making regarding development projects affecting historic resources. In this era of rapid growth and change, tracking development activities in specific areas helps assess cumulative impacts to resources geographically. The data is also informing updates to the city’s community plan program. These local-use plans guide future growth and development in neighborhoods throughout Los Angeles. Comprehensive historic resources information helps planners and community members work together to develop goals and policies that recognize and protect important historic and cultural resources.

While HistoricPlacesLA serves as the city’s internal historic resources inventory and management system, it is also the public portal for the data. This means that other departments and agencies, both within and outside of the city can and are using HistoricPlacesLA, oftentimes to obtain information regarding properties under their management. Property types include city parks, fire stations, libraries, schools, hospitals, and bridges, and knowing which properties are significant helps in the development of long-range plans regarding properties that may need updating as well as those that may be decommissioned. Recently, the Office of the Mayor, the OHR, and Mount Saint Mary’s University collaborated in planning and hosting a community research event for Women’s History Month to establish a list of influential women connected to the history of Los Angeles. Volunteers searched through SurveyLA data for notable women, ultimately aiding in the development of the Los Angeles Women’s Rights theme, underway at the time, and launching a Los Angeles–based “Put Her on the Map” initiative that aims to increase the number of streets, landmarks, and monuments named after women.23

As we look forward, perhaps one of the greatest opportunities for HistoricPlacesLA is as a tool to promote greater inclusivity in historic preservation. Using data for analytical purposes, particularly through mapping, can indicate where the city’s important ethnic and cultural resources are located and can serve both as an indicator of changing demographics and an identifier of places that are largely unrecognized in designation programs. The data can also help expand public perceptions of historic preservation to include a wide range of historical themes and types of cultural resources.

In the coming years, as both HistoricPlacesLA and Arches mature, uses of the data will grow. From the city’s perspective, promoting full use of historic preservation data requires a greater level of interdepartmental and intradepartmental collaboration and information sharing. And to accomplish the goal of reaching a wider preservation audience in a more advanced digital age, a crowdsourcing feature to enhance public outreach can draw upon the successes and failures of the MyHistoricPlacesLA program implemented for SurveyLA. The city’s big and growing heritage dataset brings with it challenges, responsibilities, and opportunities. As Los Angeles moves forward, and as big data continues to inform the city’s preservation practices, the lessons learned can influence the heritage field internationally.

The $2.5 million grant agreement called for a dollar-for-dollar match from the city.

Interestingly, the 1962 ordinance predates the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act and the establishment of the National Register of Historic Places.

City correspondence files are available in the OHR.

In general, SurveyLA considered resources constructed up to 1980. Surveyors had the discretion to record more recent resources, guided by historic contexts.

The GCI provided some funding for the application as part of its technical support for the project, but the customized application was not designed for longevity. The software is now outdated, and there are no plans to upgrade it as the field surveys are complete.

Pilot surveys were completed to test survey tools and methods before the official surveys began.

“Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Preservation Planning” (National Park Service, 2001).

Los Angeles’s city historic context uses the term “eligibility standards” instead of “registration requirements.”

Designing a citywide HCS from the ground up has the advantage of providing a structure that is both flexible and expandable over time. As new surveys are conducted, new themes can be added for topics not previously addressed or recognized. See a list of contexts currently in use at “Historic Contexts,” SurveyLA.

The GCI grant did not include funding for outreach. The city used Certified Local Government grants to fund production and translation costs of most of the materials used to inform and request input from the public.

Public outreach involved organizing a SurveyLA advisory committee, developing a website, and producing an Emmy award-winning video for the city’s cable television channel. It also included programs designed to directly involve the public in various aspects of the project. This outreach helped build support and also supplemented the project budget in much-needed areas.

The questionnaire can be accessed at “Contribute Information to SurveyLA!,” SurveyLA.

The MyHistoricLA webpage on the SurveyLA website has been updated, and content has changed.

In many cases, resources identified—regardless of age or property type—are the only tangible connection to the story or history they represent and with which they are associated.

Though the unrest spread throughout Los Angeles, this intersection and the location of the beating of King are the two locations most associated with the 1992 uprising.

Even though state and local designation programs may not have a fifty-year rule for significance, this National Register rule still guides most survey work in the United States.

See the Arches website.

See the HistoricPlacesLA website.

“Standards & Interoperability,” Arches Project.

HistoricPlacesLA currently holds about 40 percent of SurveyLA data and also includes partial data for the city’s designated resources.

The Department of City Planning manages an online GIS-based database that is currently incompatible with HistoricPlacesLA. This parcel-based database does not support more than minimal information on historic resources. As it remains well used, the ultimate goal is to have the definitive records in HistoricPlacesLA connect to the city’s parcel-based database in real time.

The Community Redevelopment Agency of Los Angeles completed surveys in some parts of the city concurrent with SurveyLA. Data from these surveys needs to be reformatted before being merged into HistoricPlacesLA.

2

Heritage Data Collection

ERICA AVRAMI

From the 1980s to the present, through positions at the International Foundation for Art Research and the Samuel H. Kress Foundation and now as the acting CEO of World Monuments Fund, you have had a privileged view of the role of data collection in the conservation of heritage, both movable (objects) and immovable (such as the built environment). Can you share some insight into how the field has evolved in the last thirty years?

LISA ACKERMAN

The impetus to categorize information is clearly something that evolved early in the history of scholarship. Whether it is the desire to map the world, document species, or identify genetic material, human resilience is linked to a quest for knowledge and the ability to organize and retrieve it. In the humanities, this is clear in the formation of encyclopedic collections of art, the creation of catalogues, and the many other examples of inventories related to the arts and cultural activity.

At the International Foundation for Art Research, one of our main projects in the late 1970s and early 1980s was the publication of a monthly newsletter, Stolen Art Alert. This was an attempt to alert museums, art dealers, auction houses, and collectors to works of art that might appear illegally on the art market. It was a valiant effort to use a printed newsletter to circulate critical information. Today, such information can be made public nearly simultaneously with the report of a theft, looting, or other criminal act.

At the same time, museums were beginning to create digital resources documenting their collections. After writing about the virtues of digitizing collections and the unparalleled new access to information that would be available because of this resource for Art Research News, in 1984 I had the privilege of attending the Second International Conference on Automatic Processing of Art History Data and Documents in Pisa, hosted by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Scuola Normale Superiore.1 This was truly a groundbreaking event, dedicated to developing standards by which museums, art historians, and research centers would agree upon methodologies, lexicons, and iconography to advance the idea of universal access to collection catalogues, archival information, and resources in the field.2 Today, it is hard to imagine there was life before the Internet and global searches. In those early days of the 1980s, however, this conference opened a new world to many of those assembled.

The Samuel H. Kress Foundation is the former owner of a renowned art collection and a significant supporter of heritage conservation projects. In what ways did the foundation’s history of managing an actual collection influence its early funding for systematic heritage documentation?

Since its founding in 1929, the work of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation in many ways established a history of caring about academic resources and access to that data. When the foundation amassed the Samuel H. Kress Collection, one of the first acts was to create a catalogue and assemble a dossier for each work of art. A number was assigned to each work acquired, quaintly called “K” numbers by staff members. But the process was far from quaint or ad hoc. Each work was photographed, described, its conditions noted, and later an X-ray was taken of each work of art. Even later, when the collection was well over two thousand objects, the foundation hired Fern Rusk Shapley to create a nine-volume catalogue of the collection. Each work was thoroughly researched, and the publication offered a brief biography of the artist, a description of the work of art, and then a thorough explanation of every instance in which the work had been publicly displayed and published. Assembling data of this nature from 1929 until 1968, the date of the Phaidon catalogues, was painstaking research—especially without the help of rapid Internet searches or indexed online reference libraries. It remains a remarkable addition to our knowledge of European old master paintings, particularly those in US public collections.

Similarly, for decades the foundation’s grant giving sought to develop scholarly resources and improve access to that information. These initiatives ranged from requiring grant recipients that produced new images of works of art or historic architecture to provide copies to the National Gallery of Art photographic archives or to make those images available in ways that benefit the field or contribute to the research of other scholars—for example, creating a database on historic stained glass in America, or contributing to the work of Corpus Vitrearum. For every area of specialization in art historical study, there is undoubtedly an inventory that has been carefully crafted. The foundation sought to encourage the growth of such databases and make them available to a wider audience. It was also an early supporter of the Index of Christian Art and paid for the digitization of the Cicognara Library of the Vatican’s collection so that scholars could remotely access its more than five thousand volumes, which are considered an important foundation for art historical study.

Most importantly, it provided access to scholars and students who might not have access to rare book collections or specialized archives, which might contain only a selection of the volumes in the Cicognara Library. These projects may seem unremarkable today, but in the predigital age, and even in the early days of digitization, these were extraordinary undertakings in democratizing access to scholarly resources.

In addition to artworks, you mentioned documenting stained glass and historic architecture. Do you see connections between the fields of movable and immovable heritage growing stronger as data collection and digitization have progressed?

Architectural preservation has been closely allied with art and art history for centuries. Raphael was charged with cataloguing Roman ruins; Palladio wrote what is considered the first modern guidebook to the architecture of Rome; Thomas Ashby of the British School at Rome created an incredible collection of guidebooks to Rome, chronicling the evolution of the city through the sites visitors were encouraged to see.

It is no surprise, then, that many of the early tools for preservation were inspired by the ideas of art historians: encyclopedic inventories of the built environment, portfolios of works by particular architects, the categorization of building types, and physical descriptions that were very similar to descriptions of art. Before long, there were calls for national inventories of heritage sites and all manner of lists and itineraries were created.

As the field of historic preservation progressed, it began to inventory threats and risks to heritage sites—problems that ranged from the physical, such as typologies of deterioration, to the more philosophical, such as rapid urbanization, climate change, shifts in population, and natural or man-made disaster. As the notion of heritage evolved, so did the desire to create databases that could help identify important places, changes to them, their risks, and in many cases the opportunity for sustainable solutions to a mounting range of challenges in the field.

At World Monuments Fund, you deal almost exclusively with immovable heritage. What have been some of the biggest challenges for systematic data collection about the historic built environment and its management?

Looking at this challenge through the lens of World Monuments Fund’s work has been illuminating and frustrating in equal measure. There is an astonishing array of information collected through site-based conservation projects, national heritage inventories, university collections, and field research. At the same time, there is the difficulty of accessing the information, fear of what ills might befall some sites if data were readily available, and the reality that much of the work is driven by limited budgets. Thus data is regularly trapped on outdated hardware and software.

In 1989, World Monuments Fund issued a report, The Razing of Romania’s Past, written by Dinu Giurescu, a Romanian scholar who chronicled the systematic destruction of historic architecture and towns throughout the country. This was followed in the 1990s by a series of publications with titles such as Survey of Jewish Monuments in Poland and Inventory and Survey of America’s Heritage Abroad: Sites of Jewish Heritage in Czechoslovakia. This collection of information was groundbreaking in that decade of discovery of what remained of Jewish heritage in former East Bloc countries after the fall of Communist rule. By the time I arrived at World Monuments Fund at the end of 2007, these publications were nearly forgotten—and yet they contained a wealth of interesting data about heritage sites. More powerful tools had been developed in the ensuing decade, and new datasets were being collected and were available in ever more practical ways on the Internet. But there was still a sense that information was not reaching a wide audience. You still needed to be involved in these projects to know the datasets were available.

Similar to the Automatic Processing of Art History Data and Documents conferences and the efforts to develop standards for and universal access to collections data, how has the architectural heritage field attempted to standardize its digital inventory data, and what challenges does it face?

As news reports of the US-led invasion of Iraq covered the looting of archaeological sites and museums, in the cultural heritage sector there was a call to do more to protect vulnerable heritage. In the aftermath of the invasion, as war and sectarian violence continued to rage, World Monuments Fund and the Getty Conservation Institute began the development of an open-access software program known as MEGA, Middle Eastern Geodatabase for Antiquities. The idea was to develop a model for creating a digital, national inventory that would improve knowledge of and access to sites in any country. As it was not possible to mount such an effort in Iraq as conflict raged, the program was implemented in Jordan, which had developed an inventory system a decade earlier known as JADIS. MEGA then transformed into Arches, an open-source heritage management tool.3 Thanks to the work of the Getty Conservation Institute, it has become a compelling digital tool driven by the needs of the field and augmented by contributions from an active online community.

Yet it is those early years and the transformation from MEGA into Arches that are most interesting when trying to understand the challenges in the field of historic preservation. The biggest breakthrough was recognizing that heritage sites are not dots on a map but polygons that need to be drawn correctly to understand the boundaries of a site. This may or may not concern the average person looking for a site, but it has vast implications for those managing a site. Qusayr ‘Amra in Jordan provides a prime example of what happens when you see a dot on a map. It can result in a road being created through the middle of an archaeological site. A polygon illustrating boundaries makes clear where a site is actually located, pushing the road around the edges of the site. From a planning perspective, understanding shape and dimensions can make a dramatic difference in decisions that affect the well-being of a heritage asset. There are many technological advancements in the software, but at the most basic level, simply moving toward a more integrated approach to mapping sites advances the management dialogue and integrates heritage into larger planning objectives.

JADIS and MEGA also demonstrated that an investment in software and hardware was not sufficient. Leaders in the field also needed to invest more substantially in training for those charged with maintaining digital inventories. Information on cards may become outdated, ink may fade, and cards are vulnerable in times of crisis. Transferring data to digital technology eliminates one set of problems but can also create new challenges, like ensuring enough people are trained to maintain the systems, to migrate the data to the next iteration of hardware and software, and to understand how and when to upgrade systems. The learning curve was substantial, which explains why some of the problems persist and why, indeed, integrated national heritage inventories are still being developed. There is no question that heritage inventories are essential tools for monitoring heritage. What we are lacking as a field is cohesive, integrated access to that data. The way in which JSTOR bundles access to scholarly texts and Artstor provides access to millions of images demonstrates that it is possible to find ways to standardize access to materials for the benefit of the scholarly community. Many universities now regularly provide open access to significant archival and library resources.

Arches is closing the gap for the heritage field in terms of easing the collection of data and the migration of information from older systems. There of course remain other obstacles, such as knowledge of the software, funds to maintain systems, and, in some countries, access to reliable Internet connections. Time, hopefully, will provide the means to overcome these challenges.