Foreword

Water Urbanism

The Urban Design Program at Columbia is investigating climate resilience at multiple scales and collaborating with partners in institutions around the world and within the University from science & engineering, journalism, conflict resolution, economics and social justice. Water is constantly in motion, changing states, crossing borders, nourishing (and destroying) life. How can water and urbanism be considered together as a generative frame for urban design practice, social life, and ecological regeneration? The spring semester 2019 design studio investigated urbanization challenges in the lower Mekong with a focus on the rapidly changing city of Can Tho, Vietnam.

As a Program, we aim to marshal the observations of the world’s best scientists and the agency of design toward action and defined, replicable climate adaptation projects in the world’s most vulnerable regions. We bring synthetic design thinking to this process and a stance of activism and engagement and believe that by building physical, resilient places we engage and educate communities about the risks they face. How we live with - and design for- water will be a central, defining element of the next century relative to climate change and urbanism. Can Tho is experiencing a number of intersecting issues relative to water and habitability with rising sea levels, land subsidence, salinization, and erosion all overlaying onto global capital and NGO activity, and a foreign direct investment boom. These conditions are exacerbated by extensive dam building in the Upper Mekong in China, that traps sediment and fish migration, lowers water levels, and creates conflict with neighbors in Southeast Asia. Our goal was to map these regional water dynamics and develop a comprehensive understanding of resilient urban systems and scales and envision how resilience overlays with a specificity of context, land, water economics, religion rural-urban pattern, decision making and governance. Our approach was both social and ecological. We aimed to visualize the complexity of interrelated risks and to imagine alternative scenarios for resilient people and places prepared to anticipate a range of future shocks and stressors in seven sites in greater Can Tho.

Students explored the dynamics of climate adaptation relative to migration and climate change, alongside the generation of new social infrastructure, public space and urban design in an expanded rural-urban context. The seven projects represented in this E-book operate at multiple scales, linking territorial interdependencies, water flows, operational landscapes, and pilot sites of detailed investigation for design exploration and on-the-ground change in Vietnam.

Columbia UD Faculty: Kate Orff (studio coordinator), Thad Pawlowski, Dilip DaCunha, Geeta Mehta, Julia Watson, Linh K. Pham

Special thanks to Dr. Nguyen Hieu Trung and Hoàng Hoài Thanh of Can Tho.

Introduction

Can Tho and the Mekong Delta

“Cần Thơ gạo trắng nước trong, Ai đi tới đó lòng không muốn về.”

“Cần Thơ, white rice, clear waters, All who come wish never to leave.”

So the saying goes in the Mekong Delta, the “rice basket of Vietnam,” about Can Tho City, its metropolitan center and its famous canal system. The Mekong Delta, a 40,000 square kilometer, low-lying region in southern Vietnam where the Mekong River ends its 4,000 km journey from the Tibetan Plateau, is a young geological formation. Most of it was formed in the last four millennia, as the river fanned back and forth across the area, depositing sediment in its wake, slowly advancing the coastline into the sea. The resultant landscape, paired with the humid, tropical climate, is marvelously fertile and biologically diverse. Since the 19th century, it has become one of the most important and productive agricultural landscapes in the world, enabled by a vast system of man-made canals. 15 million Delta farmers produce more than a ton of rice per person each year—enough to feed 60 million people worldwide. It is also steeped in historical conflict, still bearing the physical and chemical scars of two centuries of colonial conquest and war-time devastation.

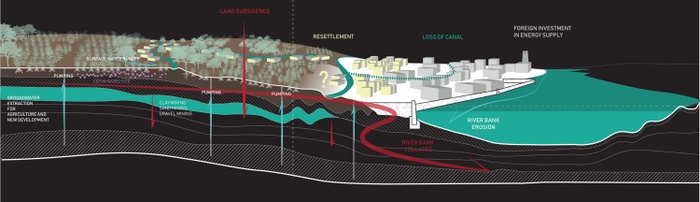

Today, The Delta remains one of the most threatened places in the world, not from war, but rather from climate change and urbanization. Upstream hydropower dams in the Mekong watershed inhibit the natural recharge of river sediment in the Delta, allowing the land to subside. Anthropogenic changes to seasonal weather patterns imperil agricultural fertility. Rising seas compound both of these threats by exacerbating the relative effects of land subsidence, thus making urban areas more prone to flooding, and by contaminating agricultural lands with salt.

Despite the urgency of these looming threats, Can Tho City has followed a model for economic modernization and urban development that closely resembles that of other cities in Southeast Asia. In an effort to transition from an agricultural economy to one based on industrial and service sectors, it has solicited foreign investment to build new factories and peri-urban sprawl. Canals in the urban core are capped or filled to make way for wider roads, or concretized with hard-edges to protect the city against seasonal floods. In peri-urban areas, agricultural lands are paved over to make way for new towns, including resettlement areas for displaced farmers. Growing industries, such as food processing plants, are powered by coal and oil-burning powerplants.

Critics fear that in an effort to modernize its economy, Can Tho is paving the way to disaster, adding pavement, heavy infrastructure and pollution to an environment already threatened by severe flooding, poor air and water quality, and land subsidence. Economic modernization and climate determinism in Can Tho are not mutually exclusive forces; they work together to the detriment of the city. Rather than controlling nature, new dikes and seawalls, resource intensive industries and road-based development exacerbate the most dangerous risks of climate change. They require increased groundwater extraction, which further exacerbates land subsidence. The proliferation of pavement in urban and periurban areas worsens the effects of extreme rain and heat events, even as such events become more common. Urban sprawl destroys fish and waterfowl habitat by way of deforestation, and leaves farmers without necessary land and resources that they need to thrive. Growing automobile usage, as well as oil- and coal-powered industry, pollute the air and water, threatening public health. So do the myriad of petroleum products that are used to protect and package agricultural products for export.

With these challenges in mind, the Can Tho Resilience office has spent the last several years studying ways that nature-based infrastructure could be deployed to address Can Tho’s most pressing challenges, and ameliorate some of the most deleterious effects of economic transition. It has sought out opportunities to protect critical ecoservices and improve community participation in civic planning projects. Columbia’s Spring 2019 Urban Design Studio and the Resilience Accelerator—a partnership between the Center for Resilient Cities and Landscapes and 100 Resilient Cities—teamed up with the Can Tho Resilience office and the Mekong-DRAGON Institute at Can Tho University to explore alternative modes for urban development guided by nature-based infrastructure and resilience principles. While visiting Can Tho, the Urban Design studio developed seven urban design principles that guided their work for the duration of the semester. Upon returning to New York, the studio re-imagined a future for urban growth that takes advantage of the Mekong Delta’s rich ecological and cultural resources by exploring novel spatial configurations and economic and institutional relationships between Can Tho City, residents, investors and other stakeholders. The student work presented here suggests that growth strategies in Can Tho can enhance the regional capacity to adapt to climate change while empowering urban and rural populations as agents of environmental stewardship.

- Gideon Finck, Center for Resilient Cities and Landscapes

Typical canal edge with houses in Can Tho

Aquaculture in Can Tho

Traditional aquaculture in the Hao River

Irrigation canal in a fruit orchard

Picking star apples on the outskirts of Can Tho

Traditional bridge in a Can Tho orchard

Water-based transportation

Commerce in the Cai Rang Floating Market

Fruit commerce in the Cai Rang Floating Market

New construction along the Can Tho River

Concretizing water infrastructure in Can Tho

New Urban Areas on the outskirts of Can Tho

“High-Tech” aquaponics on the outskirts of Can Tho

Stagnant water and fortified edges in central Can Tho

Packing fruit for export

River fortification and concretization

Wastewater treatment facility in Can Tho

Principles

Seven Principles for a Resilient Can Tho

1

[Re]Flow Can Tho

Students: Shivani Agarwal, Hsin Yi Chao, Greg LeMaire, Tanaya Kadam

What if we were to reconnect the movement and flows of the urban hydrological cycle to the city of Can Tho and its people?

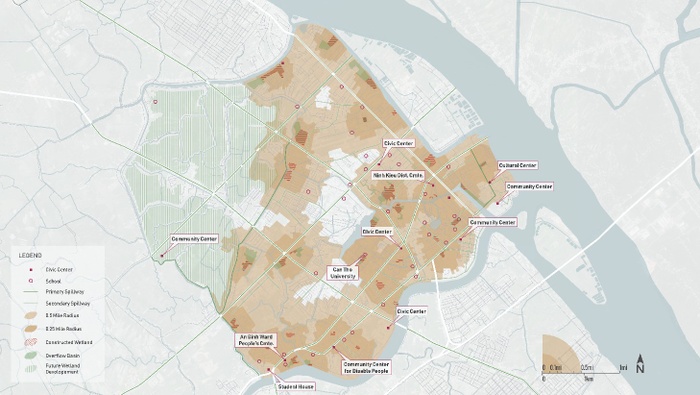

As the largest city in the Mekong delta, Can Tho was built on top of an ever-changing, watery, delta landscape. This delta is sinking as urbanization consumes more groundwater and the sources of groundwater recharge such as wetlands are diminished. This culture that has traditionally lived with water, is being disconnected from it by rapid urbanization and a focus on land and road based development. By introducing a new system of urban water flow over the existing city fabric, [Re]Flow reimagines how Can Tho lives with water. To bring water into and through the urban core, a network of canal-like spillways will be cut through existing overbuilt roads, reviving a lost system of tandem road and canal based development. To allow for safer interaction with the urban waterways, reflow will also completely remove the sewage discharge from the canals through a distributed system of constructed wetlands, built on existing green spaces, which will treat the wastewater and use the treated water to recharge groundwater. With these interventions [Re]Flow increases the city’s ability to live with water and respond to its changing dynamics.

![[Re]Flow is a city wide strategy, reimagining urban flows for a more resilient Can Tho](https://d37vpt3xizf75m.cloudfront.net/api/file/BLfmo45oR92TUYnbuyQ5/convert?fit=max&h=550&w=700&compress=true&fit=max)

[Re]Flow is a city wide strategy, reimagining urban flows for a more resilient Can Tho

Project Introduction Video

Urbanization

In recent years Can Tho city with backing of the World Bank, has dealt with flooding by channelizing canals and creating hard edge holding basins. This combined with a lost network of canals has essentially created a series of disconnected tubs, which disrupt the natural flow of water.

Can Tho’s growth, 1970-Today

In the rush to urbanize, it seems as though Can Tho has given far too much space to cars. Recently built six to eight lane highways criss-cross the city, spreading a blanket of asphalt over the sinking delta landscape. Many more roads are planned, and with them more cars and more parking. These roads might help the city expand economically (and geographically) but they also prevent groundwater recharge, and hasten the subsidence of the ground on which the city sits.

Flooding + Pollution

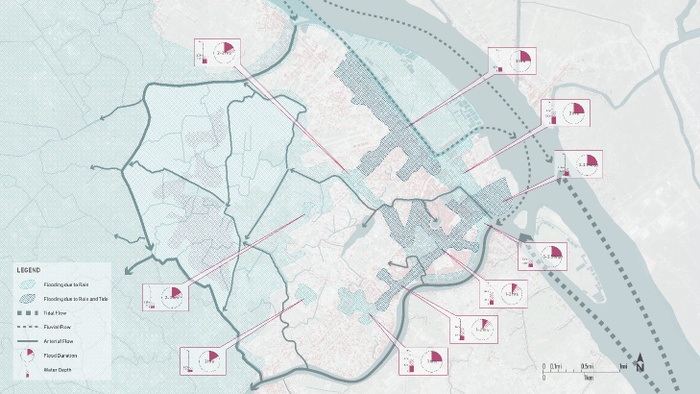

Can Tho City suffers from regular flooding, two times per day during the wet season, and the frequency is only expected to increase. The current solution to this is a 3 foot high embankment around the urban core, which will likely not be effective past 2050 is putting the city into debt.

High tides combined with river discharge and heavy rains regularly flood Can Tho’s urban core

Overbuilt roads stretch across Can Tho, a byproduct of rapid urbanization

Flooding interrupts daily lives and flows in Can Tho

Flooding interrupts daily lives and flows in Can Tho

Flooding interrupts daily lives and flows in Can Tho

High tides combined with river discharge and heavy rains regularly flood Can Tho’s urban core, disrupting traffic flows and daily life.

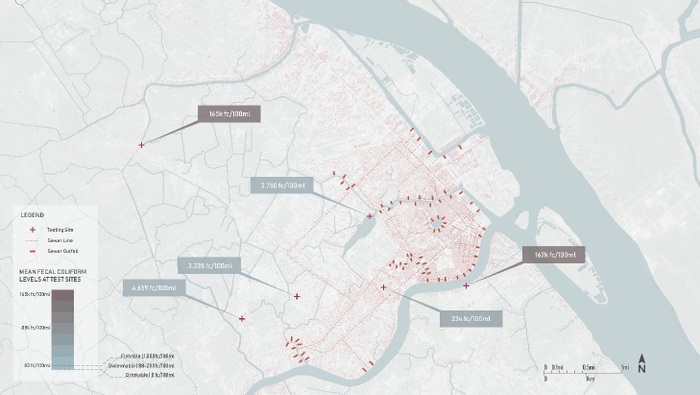

Sewer outfalls + pollution levels in Can Tho

Extreme pollution conditions produce black water and attract invasive species, like the apple snail eggs seen here

Sewer outfalls throughout the city dump sewage directly into urban waterways

Polluted water creates risks for both human and environmental health

Measured levels of fecal contamination in Can Tho regularly show elevated and dangerous levels of pollution. However, residents still regularly interact with the water, swimming, bathing and washing in it.

Constructed Wetlands & Canals

In the existing system, untreated sewage flows directly into the canals. By introducing recharge parks with bio-filtration and rerouting the city sewage network we can not only clean the waste but also recharge depleted aquifers, reducing subsidence. By greening streetscape and canals edges, more of the excess water can be displaced back into the ground and overflow can be taken by low lying basins.

Transformation of the existing city infrastructure to treat wastewater and recharge groundwater

Recharge Parks also serve as cultural gathering spaces, reactivating a connection to water

Road Spillways

To deal with increasingly regular seasonal flooding, [Re]Flow proposes creating a network of spillways through existing overbuilt 6 to 8 lane roads. During the dry season the spillways act as a linear greenway, bringing life and activity to city streets. When the monsoons arrive and the tide rises, the spillways absorb water which would normally flood the surrounding streets. This will allow for water to more easily move through the city and rain water to be held and released.

Existing overbuilt roads are transformed,l holding and moving water through city streets

New linear greenways and spillways will reflow people and water through Can Tho

Neighborhood Scale

At a neighborhood scale local residents and businesses become stewards of the system. These neighborhood stewards activate and maintain both Spillways and Recharge Parks throughout the city. In return they can use the public space for things such as kitchen gardens, market sites, and handicraft spaces and workshops.

![[Re]Charge An Hoa shown after implementation, wet and dry season](https://d37vpt3xizf75m.cloudfront.net/api/file/YwLTIS5MTrCvd5QOIgVJ/convert?fit=max&h=550&w=700&compress=true&fit=max)

[Re]Charge An Hoa shown after implementation, wet and dry season

Steward sheds around the city’s ReCharge parks

Conclusion

By reconnecting Can Tho to its deltaic roots, we can not only reflow hydrological cycles and waste, but also reflow people’s daily lives, reimagining a lost connection to the water and surrounding landscape. [Re]flow can be a model for growth not only for Can Tho but for increasingly urbanized deltaic landscapes around the world.

An activated greenscape through downtown, Can Tho

2

Life Aquatic

Students: Students: Junyu Cao, Zeyi Jiang, Ashley Louie, Dian Yu

What if landscape and cultural conservation could be a driver for adapting water-based livelihoods into resilient growth?

Symbiotic Urban Growth and Cultural Conservation

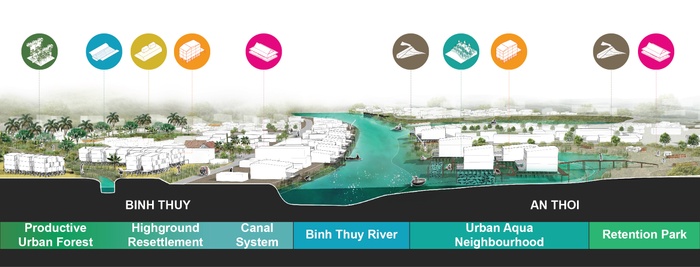

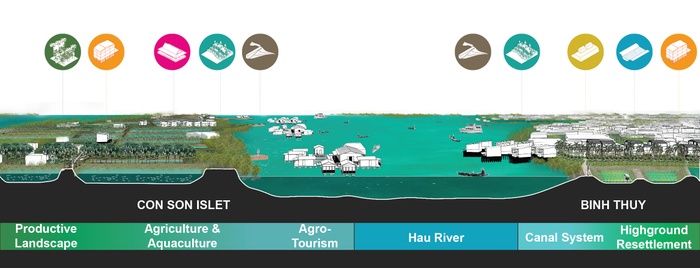

The oldest urban area in Can Tho, Binh Thuy is a site of historic temples and heritage houses adjacent to vernacular stilt houses on the water. As the city rapidly urbanizes, roads are becoming canals, sea walls are replacing stilt houses, and impermeable surfaces are covering green spaces. With the displacement of its people and water landscape, Can Tho risks losing its identity and resilience, becoming more vulnerable to subsidence and sea level rise. Addressing this risk, landscape and cultural conservation becomes a driver for adapting water-based livelihoods into resilient growth. The boundaries of conservation expand beyond preserving historic landmarks; vernacular infrastructures and their systems, such as wetlands, dikes, canals, docks, floating structures, and stilt houses, are identified as culturally and ecologically resilient public assets that protect the city and its people, while promoting development and growth. The co-benefits of this adaptive conservation strategy include biodiversity, food security, job diversity, and public green space.

Project Introduction Video

Vernacular Cultural Elements: Stilt Houses along Binh Thuy River

Vernacular Cultural Elements: Fish Ponds on Con Son Islet

Vernacular Cultural Elements: Infilled Canal in Binh Thuy Historic District

Generations of Vietnamese people have evolved a culture that symbiotically engages water and the fosters aquatic livelihoods throughout the Mekong Delta. The coexistence of aquaculture and agriculture within urban settlements allows Can Tho to retain its productive relationship with the water, while providing resettlement alternatives for farmers to continue their agrarian livelihoods and to steward the resilient landscape.

Passive Preservation of Isolated Existing Structures, Binh Thuy Temple

Active Conservation of Integrated Productive Cultural Landscapes, Floating Aquaculture Farm on Hau River

Many of the vernacular built elements enrich this symbiotic relationship with water, fostering a life aquatic. The cultural landscape deserves re-evaluation and protection, amplifying conditions for existing and proposed settlements to accommodate excess water during the wet season, and retain water during the dry season.

Binh Thuy River Existing Transect

Hau River Existing Transect

Binh Thuy has a rich cultural landscape, but it’s at risk of losing its water identity. The many canals and dikes provide infrastructure for the productive aquaculture and agriculture livelihoods, while floating structures and docks allow people to live directly on the water and to access the water for domestic cleaning. A number of temples and cultural heritage sites are also situated throughout Binh Thuy, visually connecting to the water and establishing a network of social infrastructure for the old urban areas. As the city rapidly urbanizes, canals become roads, embankments displace stilt houses, and impermeable surfaces replace green space. The national highway and the following land-based development threatens to eradicate the water retaining landscape and, by extension, the livelihoods that depend upon it. The World Bank funded embankment, already in construction, will replace stilt houses and access points to the water with a hard impervious edge along An Thoi. Additionally, a proposed cable hanger to enhance tourism on the Con Son Islet will further disconnect people from the boat culture on the water.

Water-Based Cultural Landscape

Cultural Landscape at Risk

Can Tho’s current ambitions to rapidly urbanize and economically grow, with flood protection that neglects the maintenance of canals, depletes the productive landscape, and reduces water access, will exacerbate its vulnerability and the loss of cultural identity. Conservation will strengthen Can Tho’s relationship with water and evolve its resilient culture and landscape, necessary for sustainable city growth. If these same goals of urbanization, economic growth, and flood protection can be achieved through conservation as a growth strategy, how might we envision a different future for Can Tho?

Can Tho Urbanization Goals: Cultural Landscape at Risk

Can Tho Urbanization Goals: Conservation as Growth Strategy

Conserve, Adapt, & Grow - Design Language

In Life Aquatic, conservation goes beyond its present paradigm of preserving historic landmarks by identifying wetlands, dikes, canals, aquaculture, docks, floating structures, stilt houses, and heritage sites as cultural assets to conserve, adapt, and replicate in the landscape. These vernacular elements can be combined and collectively adapted into hybrid systems that are both productive and resilient growth strategies throughout Can Tho.

Conserve and Adapt Typologies to Integrate in Growth Strategy

Conserve Cultural Elements

Adapt Water-based Typologies

Growth Design Strategy

Conservation as Design and Growth Strategy

Expanding the definition of conservation begins with a re-exploration of the physical elements, followed by assessment, identification, and expansion of new built elements which expand the physical conservation grounds of the city. Can Tho’s conservation landscapes are then adapted to let water in and expand water-based developments to create new areas that simultaneously grow while conserving the physical elements connected with water, deployed throughout specific site conditions in An Thoi, Binh Thuy, and Con Son.

Identify and Expand the conservation elements in Binh Thuy

Adapt Elements to Accommodate Urban Growth

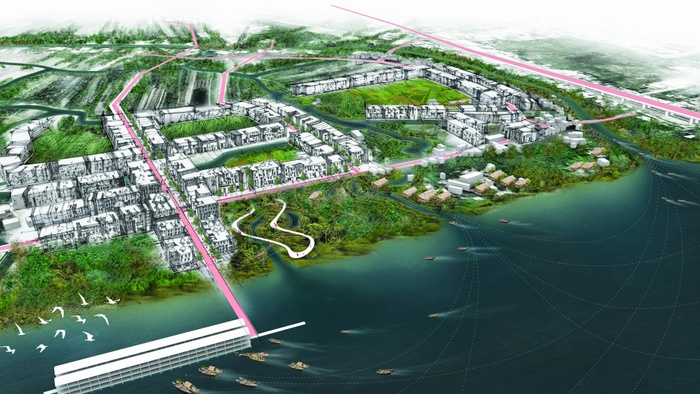

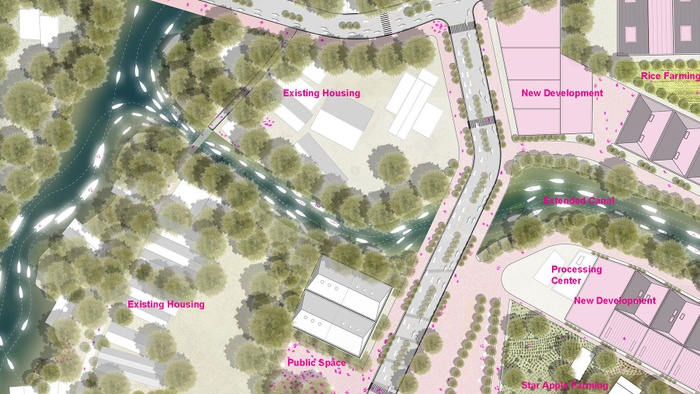

Life Aquatic adapts the existing green spaces and stilt houses to form an absorptive softscape along the An Thoi waterfront. Reintroduced canals throughout Binh Thuy and An Thoi extend the areas that water can flow into the city, while connecting green spaces within an integrated water holding system. Cutting and filling land will allow new developments to grow on high ground along these canals, while stretching dikes to accommodate improved circulation routes throughout the Con Son Islet. A series of groynes along the waterfront edges gradually gather sediment, to build land foundations for new mangrove forests and to provide access points for water ferries. New floating lodges integrated with floating aquaculture and agro-tourism learning centers throughout the Con Son Islet will generate additional revenue while also supporting the local aquaculture and agriculture livelihoods and landscape, and enhancing water-based transit connections.

The conservation and design of Binh Thuy is shown through two transects: Binh Thuy River (connects Binh Thuy and An Thoi) and Hau River (connects Con Son Islet and Binh Thuy)

Reviving Canals and Reconstructing the Edge: Binh Thuy River Transect

The Binh Thuy River connects Binh Thuy with An Thoi, the city center of Can Tho. In lieu of the proposed World Bank embankment in An Thoi, a gradient of softened edges will retain flood water, cleanse greywater, preserve connectivity and accessibility between water and public space, and produce urban aquaculture, agriculture and washing platforms. New and revitalized canals extend inland into Binh Thuy, creating more opportunities for housing developments on higher ground to coexist with pockets of urban agriculture.

Binh Thuy River Transect

The coexistence of aquaculture and agriculture within urban settlements allows Can Tho to retain its productive relationship with the water, while providing resettlement alternatives for farmers to continue their agrarian livelihoods and to steward the resilient landscape. Creating a productive urban forest interstitched with densified housing areas will foster new communities that continue lasting stewardship of the land, while diversifying job opportunities and connecting people with urban resources.

Introduce Canal in Existing Street

Productive Terrace

Elevate Stilt House and Extend Absorptive Edge

Integrate Urban Aquaculture

In order to conserve and extend the canals, polluted and neglected canals will be restored, and cut and fill strategies can elevate existing roads with water flowing under pedestrian paths. For areas along the Hau River, where the hard edge World Bank embankment has already been constructed, the edge will be transformed into a vegetated terrace for water purification and accessible platforms for passive recreation and fishing. For the immediate short term, existing half-stilt houses along the water edge will be adapted with an additional story for the living spaces, and allow the ground plane to flood while doubling as a water retaining wall. These half-stilt houses will gradually be reconstructed with a grid-system of bamboo supports as full stilt houses that integrate aquaculture farms and stretch the floodplain inland as a water retention park during the dry season.

Multipurpose Aquaculture with Tourism and New Development: Hau River Transect

The Hau River connects multiple economies between the Con Son Islet with Bin Thuy. As a tourist attraction, the floating aquaculture farms and agriculture on the Con Son Islet can be conserved through the strategic adaptation of dikes and addition of learning centers and floating lodges to accommodate visitors. Cut and fill for new fish ponds and high ground development in Binh Thuy extends this productive aquaculture and agriculture network and creates a new community for cultural livelihoods to coexist with urban growth.

Hau River Transect

Integrating agro-tourism, aquaculture, agriculture, and new development supports a diversified economic model for Binh Thuy. New floating villas provide tourists with a place to stay and agro-tourism destinations educate visitors on the active cultural conservation of the landscape while yielding additional income to farmers, creating new hospitality jobs as innkeepers, translators, and tour guides, and maintaining the water-retaining landscape.

Broaden Dikes for Circulation and Programming

Integrate Agro-Tourism with Aquaculture, Agriculture, and Landscape

Develop High Ground

Densify Productive Urban Forest

In addition to retaining water for fish ponds and preventing the island from flooding, widened dikes accommodate circulation throughout the Con Son Islet. A series of groynes are introduced along the waterfront edge to gradually accumulate sediment for the subsiding land and to provide docking access to passenger ferries. Visitors can participate in planting mangrove seeds, which will mature into a naturally protecting forest from erosion. On Binh Thuy, the creation of low ground bioretention swales and high ground platforms for new urban development will create a multi-level ground plane that can adapt to seasonal flooding and provide space for productive fish ponds, rice paddies, and multi-layered fruit tree canopies.

Conclusion

Adaptive Typologies

When these adaptive elements are deployed within one site in Binh Thuy, people conserve a stronger relationship with the water. Elements that facilitate these water connections and enrich productive aquaculture and agriculture livelihoods, accommodate seasonal water flows, enrich existing communities, and provide opportunities for densified growth.

Water-based Social Infrastructure Network

Productive Urban Aquaculture

Symbiotic Urban Growth with Water

Renewable materials, such as wood and bamboo, reinforce the vernacular construction techniques and employ local labor to build these adapted typologies. Incorporating aquaculture and agriculture alongside new developments provides resettlement opportunities for displaced farmers who cannot sustain a livelihood in urban areas, while supporting a way to steward the land. Through the conservation of livelihoods and the landscape, economic investments for agro-tourism can benefit the local people and environment. Letting water into Can Tho proposes an alternative flood protection strategy to the hard edge embankment, while activating social spaces along these added water adjacencies. Landscape and cultural conservation are necessary for Can Tho to retain its relationship to the water and grow resiliently.

Aquatic Life in Binh Thuy, Can Tho

3

The Urban Frame

Students: Aniket Dikshit, Mariam Hattab, Berke Kalemoglu

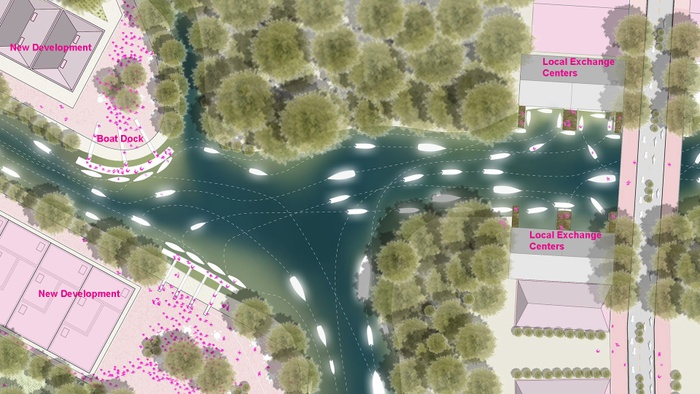

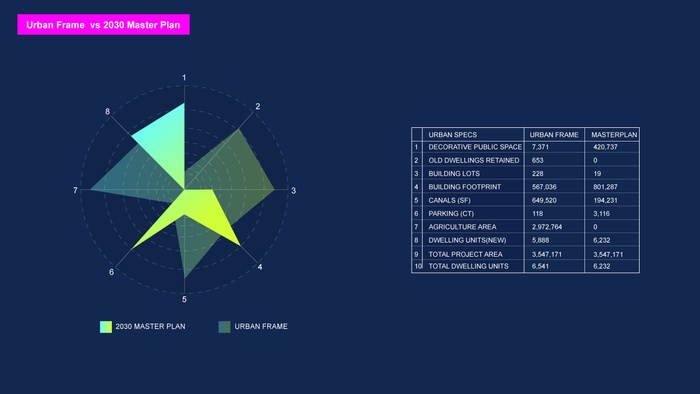

What if the new economic urban development strategy in Cai Rang East is led by water and landscape?

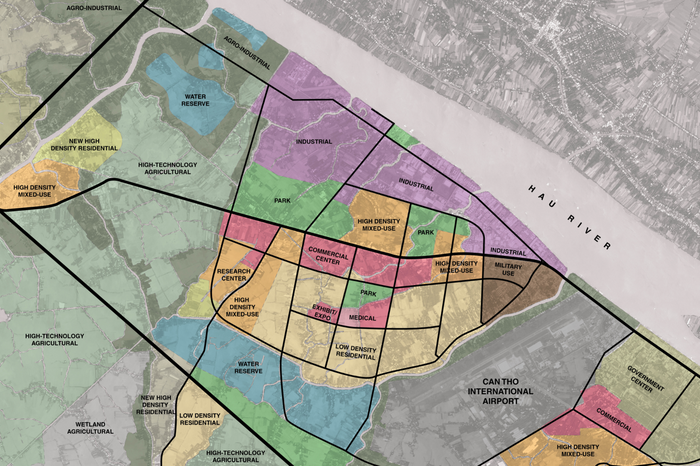

FDI has been a driving force for development in the country of Vietnam, especially in the Mekong Delta. While agriculture contributes to more than a third of the GDP, FDI is concentrated in the Processing and Manufacturing sector for which the local residents are not trained. Allowing for a major shift from an agriculture to a service-based economy. This has entailed an age-old situation of International as well as rural-urban migration. Can Tho has proposed a new masterplan to accommodate these nonresidents, where the city has embraced a development strategy of ERASURE and REPLACE.

The proposed development model is a methodology where the old and new can coexist, allowing for a “BUILD AS YOU GROW,” rather than a “BUILD AND THEY WILL COME” strategy. The Urban Frame addresses the growth of Cai Rang East, Vietnam by challenging an existing masterplan that is destructive to the existing landscape and carries a “tabula rasa” approach, through creating an alternative scenario to a Vietnamese urban model that embraces water edge conditions, focuses on a preservative rhetoric, and expands on the agricultural assets of the landscape. The Urban Frame focuses on populating residences by delineated canal bodies, while maintaining a productive lanscape inwards of the frames, in addition to narrating an economically viable and stimulating network that is created throughout the replication of the frames.

Project Introduction Video

The Expansion of Can Tho

Cai Rang East is a new town where money is being directed to, and real estate development is exponentially increasing, we are positioning ourselves as trying to acknowledge this phenomenon, but we are trying to shift the priorities and shift the spatial practice of this new development to continue to include productive landscapes and connection to the port, to ensure that hydrology is not decorative but is still core to the fabric to resist flooding in Can Tho.

Cai Rang East’s development vision

Incremental Development and Canal Oriented Planning

We propose to address the current and future challenges of urban development through identifying the existing productive landscape, strategically extending the water canals without intruding agricultural parcels, identifying and preserving the existing dwelling units, creating local economic confluence points throughout the city with minimal road infrastructure and framing the existing assets by strategically placing the new developments.This water and landscape led strategy can be implemented incrementally as a build as you grow strategy rather than a build and they will come. By keeping and extending the existing canals through the boundaries of agricultural parcels, at low grounds where drainage infrastructures can be improved, we’re proposing to create a network of water based transportation.

Preserve existing agricultural land

Delineate productive canal network

Maintain and expand on the existing residential districts

Outline essential road network

Aggregate the frame

Proposed development scenario of The Urban Frame

The New Urban

Our development methodology focuses on laying out a mix of building typologies that frame the edges of the existing productive landscape, embrace hydrological corridors, and support a comprehensive pedestrian network.

Strategies such as minimizing the road network, emphasizing canal based transit and a pedestrian network are critical to The Urban Frame model of living, in addition to retaining agricultural fields, and adding a local processing centers, we boost the local economy by connecting these individual parcels to the city wide boat network.

The new housing is an extension of the existing housing, and embraces an economy of agriculture.

The local exchange center placed at the confluences of the canals, allowing for boat traffic, these local exchange centers are connected to the district port.

Activate the Water

We imagine a community that embraces a delicate architectural pallet that reflects the existing housing typologies, and focuses on urban agriculture and density resulting in a diverse socioeconomic living model.

A streetscape that embraces public spaces, resilient parks, a narrow street network, all while maintaining street activities that are important to the people of Can Tho including urban potting in preparation for the lunar year and other festivities. By proposing a new district port, we connect the local market in cai rang east to numerous city wide local markets and the cai cui port.

How can we build from the land patterns that are there and focus density in such a way that these canal networks can be rehabilitated?

Plan of the Can Tho District Port

Urban Frame’s development summary

Regional Frame for Cai Rang East

As the agriculture fields and traditional housing typologies of Can Tho are disappearing today, the proposal for the westernized tabula rasa developments strategies have become critical threats to local residents, agriculture fields, and the canal network, in which the locals heavily depend on.

We’re positioning ourselves in this process of bulldozing and changing by asking “What if the new economic urban development if Cai Rang is led by water and landscape?”

Perspective showing the Cong Vien urban park along with the district port.

4

Reconnect To Biosphere

Student: Alaa Marrawi

What if the social - ecological corridor become the main formation for the resettlement area to influence the resilient strategy for the entire Can Tho City?

The study area is called the resettlement areas , located in the" Peri-Urban" zone, for residents displaced by recent infrastructure projects in Can Tho. The project vision is to reconnect the An Khanh ward citizens to their biosphere (land, water, and the air) by creating social and ecological corridors. These corridors have the potential to recouple the natural capital and the human capital as one integrated system. This system allows the ecosystem to reach its full capacity, improve human wellbeing, and provide a natural buffer from flooding. The project embeds microclimate topography into hybrid social plazas along the corridor and new housing typology, to restore a healthy, resilient, and productive landscape. The social-ecological corridor will be introduced as green arterials in between the housing dwellings to serve as social ecological synergies between inhabitant, nature and the rest of the city.

The future of the resettlement area of An Khanh ward in Can Tho. The design strategies should depend on the social and ecological corridor as the main skeleton of the development strategies to achieve resilient adaptable future of Can Tho.

The future mirror of the existing one of the resettlement area in Can Tho (An khanh Ward), when will be planned in the future based on the productive adaptive social-ecological corridor).

Project Introduction Video

The resettlement area “ Peri-Urban” zone of Can Tho current situation

The Peri-Urban zone is located outside the dense urban core. An Khanh ward is one of the resettlement area which is the project focused on. Displaced residents from infrastructure and development projects, who were largely farmers lost their productive land, are typically allocated land, which is transferred by lease. Although the city provided the farmers within the land parcels and the utility services in the resettlement areas, residents are financially responsible to build their houses (with two or more stories). Residents who cannot afford the construction cost often opt to sell their land leases to more affluent individuals or developers and move to agriculture areas farther from the city center. This displacement process had direct impact on the livelihood, the public health, the ecosystem and the community bonds. Along a canal within An Khanh ward, the City of Can THo has made some preliminary designs for a neighborhood park and has asked for guidance in considering how ‘green infrastructure’ can play a role in the development of this park.

The impact of the climate change has been gradually affecting Can Tho city with more flooding and heavy rain events.

This urgent situation leads the city to have the Can Tho Urban Development and Resilient Project (CTUDRP) to protect the community from flooding by increasing the embankment and the hard infrastructure along the river. Towards this project, the city published a resettlement action plan to allocated the citizens who live in the area that needs national purposes.

City map that shows the location of the resilient project, the resettlement areas and how the increasing urbanization has been impacting the agriculture fields

An Khanh Ward site is the study area which is one of the resettlement areas of Can Tho.

The map shows the main features of the productive landscape within the agriculture, aquaculture, and fruit fields in 2003 before the resettlement process start and how the urbanization has erased this system of values.

Some of the site photos that represent the huge scale of impervious surfaces, the productive canal edge, the community activities, and the skinny houses which are very narrow and close together.

The site, while technically unprogrammed, is actively used by community members for small-scale crop cultivation, including banana trees, as well as staging for construction materials. There is also a large shade canopy fronting the street, with a palm-thatched roof covering about a dozen hammocks and half a dozen tables.

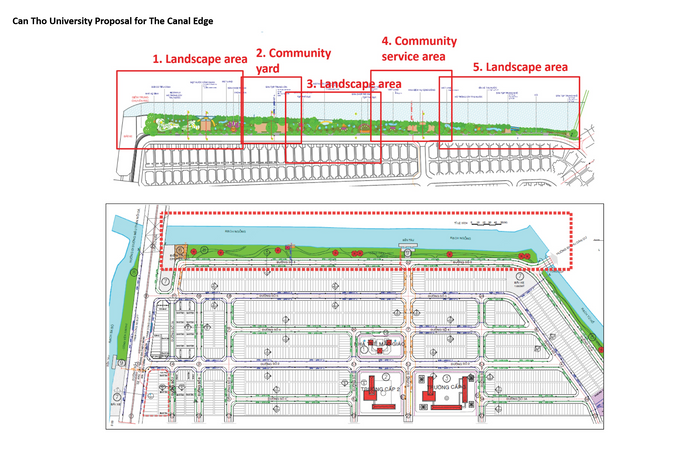

Can Tho University Proposal for The Canal Edge

The site has been proposed for future development as a neighborhood park at the water edge. The Can Tho University has a proposal depend on creating a recreational park and integrated it with water management systems.

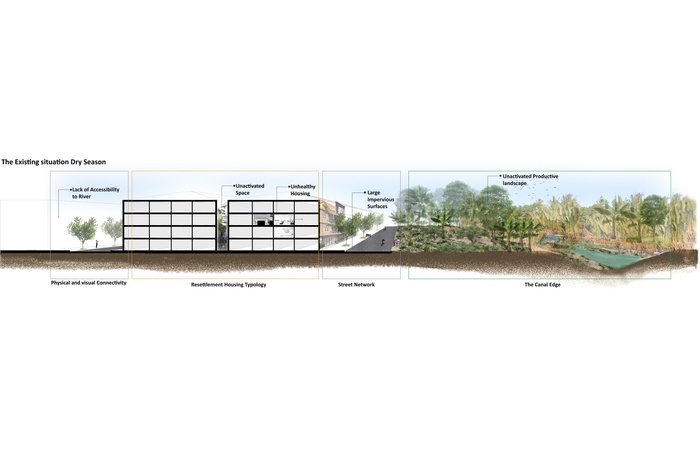

Xray of the current issues

The An Khanh Ward was built recently, with many houses today rushing through construction. Most of the houses are single-family, two to four stories, on narrow lots (3 meters), but some houses are up to six stories, with large garages on the ground floors. The zoning only requires two meters (?) of setback from one building to another and the spaces in between tend not to be a cared for. The streets are very wide for a residential neighborhood and there is no commercial activity evident at all, unlike most other residential neighborhoods in Can THo. In the recent years most of the streets are flooded during the rainy season due to Increasing the impervious surfaces impacted in increasing the urban runoff.

An Khan Ward Existing Resettlement Urban Fabric

This image is showing the site parcels and the disconnectivity to the canal edge. The impact of the urbanization process through the years in the landscape. In 2002 the building was just 11% and The Vegetation was around 65%. However according to the resettlement process through the years the site now has occupied by high dense housing and the road network.

Xray Drawing of The Existing Resettlment Housing Typology

New housing typology has created which is called Liner Tube house. The houses attached to each other. The main feature of the urban fabric is the narrow closed houses,fragmented patterns of the agriculture and a wide road network. These new resettlement cluster has directly impacted the public health, the ecosystem and the livelihood.

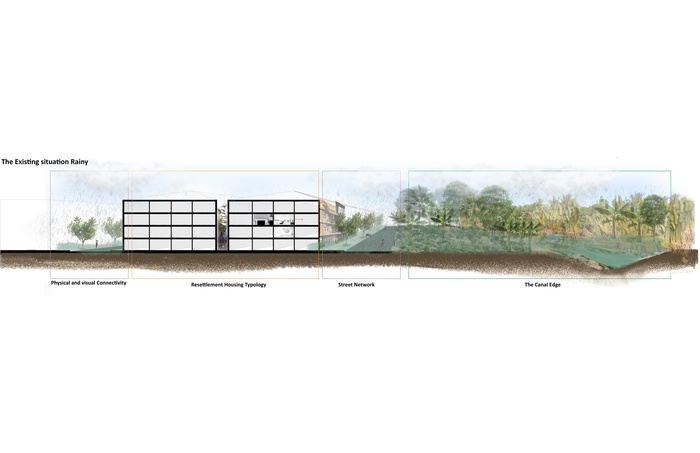

An Khan Ward Existing Resettlement Urban Fabric

The section shows the disconnectivity between the canal edge with lots of coconut trees, banana trees, jackfruit and the urban fabric with the new housing typologies with limited opportunity for natural ventilation, physical and visual access to the river.

The impact of the urban runoff during the rainy season.

** Project vision**

The project vision is to reconnect the site and the residents to their biosphere (land, water, and the air). The main methodology is creating a sustainable, healthy and productive liner landscape across the site. The objectives of the final intervention is improving the public health mentally and physically, enhancing sustainable agriculture practices and providing ecological corridors that will integrated with multipurpose civic infrastructure for a future resilient Can Tho.

The Social - Ecological Corridor Vision

Looking to achieve SDGs Goals (3,11,13,15,17), the social - ecological corridor vision is targeting to create system of social_ecological values and value sharing between the human capital and natural capital. Eventually this integrated system will enhance a synergic relationship between residents and their biosphere.

The proposed design framework functions like the human body.

Different activities will take place in this park like the muscles in the human body that keep the An Khnah ward citizens active. The greenery network will have green infrastructure that will absorb the rainwater and keep the whole area functions as the veins in the human body. The new housing typologies will integrated with a Co Op farm that will function as lungs in the human body to keep the An Khnah ward citizens alive.

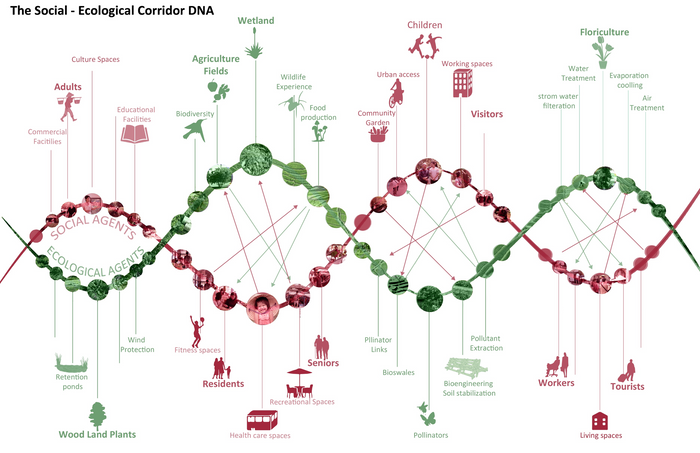

The Social - Ecological Corridor DNA

The DNA of the corridor identified by the social agents and the ecological agents to recouple the social actors and their services with the ecological actors and their services.

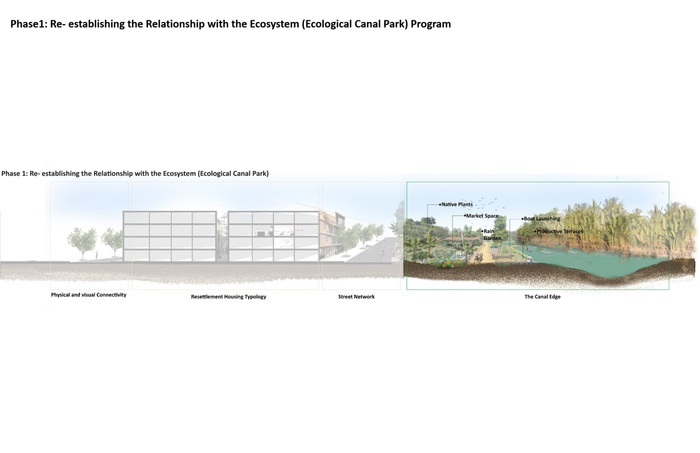

Phase 1: Re- establishing the Relationship with the Ecosystem (Ecological Canal Park)

The linearity of the corridor in the three project phases will maintain a sense of openness to nature, encourage human traffic flow, minimize urban runoff, stay close to nature and green spaces and enhance the biodiversity by naturalized the canals. The social - ecological corridor will be integrated with hybrid social places along the corridor for having different community activities. At the same time, using the strategy of the micro topography will work as a holding system for the rainwater during the rainy seasons. Enabling theses socio ecological spaces to function as an significant component of the green corridor and to provide shared flexible spaces for the community where work,play, and social activities can occur.

Ecological Canal Park part of the activities based on community needs that are integrated with a rain garden as a main strategy of the green infrastructure.

Ecological Canal Park along the canal edge as a multipurpose civic infrastructure.

Different moments of the park that shows the entrance with the food market, the hamak, Bamboo footpath, Banana trees, native species, floriculture, playground, boat launching.

Activated canal edge with different social activities

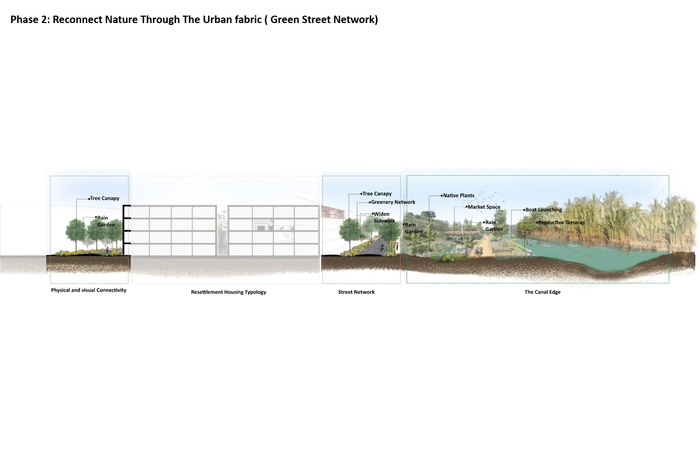

Phase 2: Reconnect Nature Through The Urban fabric ( Green Street Network)

Stretching out the park to the urban fabric to extend the greenery network and enhance the sustainability and resilience in the entire site.

Street strategies based on shrinking the roads, widden the sidewalk, increasing the vegetative cover, apply rain garden strategies and create a pleasant environment to walk through.

The green street view with native plants and increase the accessibility from the housing toward the park.

The new green street strategy section

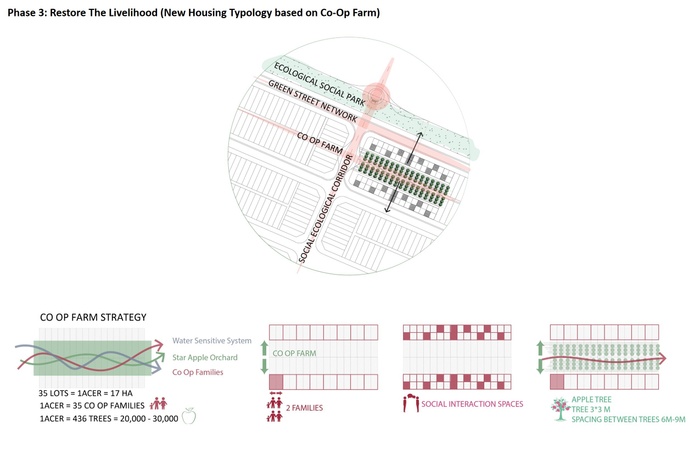

Phase 3: Restore The Livelihood (New Housing Typology based on Co-Op Farm)

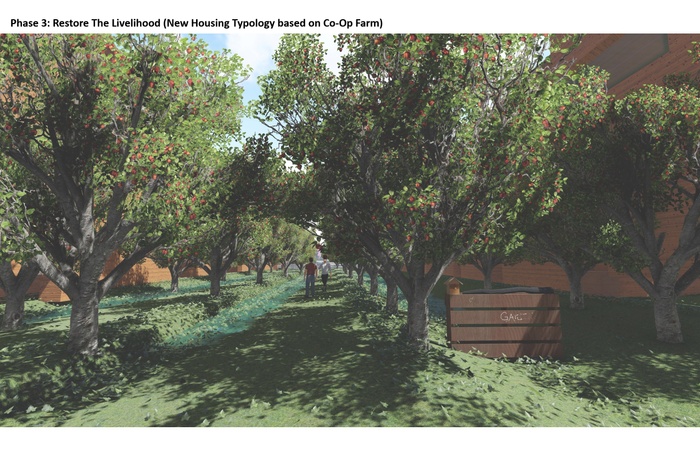

The new housing typology will optimize the ecological function of a housing block through different methods. The design of the house will help to exposure to the sunlight and enable natural ventilation. The roof of the house will harvest the rainwater for storage and use for irrigation. Integrated apple orchards between the houses will restore the livelihood of the residents, create a sense of community activity where families go and pick food and eat together and connect the housing fabric with the larger green network.

Approaching the same existing density with a resilient approach by having apple orchards between the housing.

The green network that is stretched out from the park to the street and the new housing typology.

The network from the park to the new housing cluster with vegetative cover for shading and cooling the spaces.

The apple orchards between the housing typologies and the micro topography system.

Dry Season. The social ecological corridor applied in the canal edge, the street and the housing typology.

Rainy Season. The social ecological corridor applied in the canal edge, the street and the housing typology.

Resilient Future

Enhancing the resilient thinking in the built environment is one of the most important approaches towards disaster risk reduction. Integrated social ecological corridor in the planning strategy to create a productive adaptive landscape that is create healthy environment for people to live in, provide them the livelihood and protect the ecosystem to flourish and maximize it services. These components will work together to better function the resettlement area, provide educational and job opportunities and allow people to enjoy the nature.

Between today and the future of An Khanh ward if it depend on the social ecological strategy. This resilient model should influence the future resettlement areas of Can Tho.

5

Leveraging Linear Landscapes

Students: Shuyuan Li, Sharvi Jain, Jianqi Li, Devaki Handa

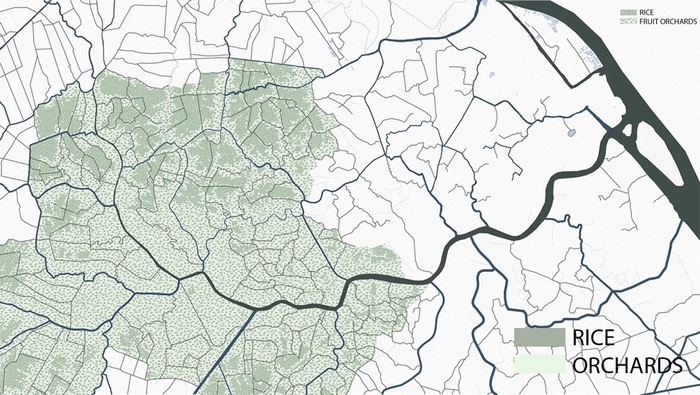

What if canal-based urbanization is embraced such that it minimizes encroachment on agriculture fields?

Project Introduction Video

Can Tho has begun to grow/urbanize along new roads that erase an agrarian economy by clearing land, fragmenting once-productive rice paddies and orchards. This urbanization pattern leads to the displacement of hundreds of farmers, and increases impervious surfaces in flood-prone areas. Our project proposes incentivizing dense urbanization along canals and the consequent preservation of farmland by leveraging the existing landscape. By revisiting the traditional patterns of building on levees along waterways, we emphasize agriculture’s economic, ecological, and social co-benefits.

Urban densification along Can Tho River/primary canal, incentivized by water based transportation.

Land Construct and Regional Economics

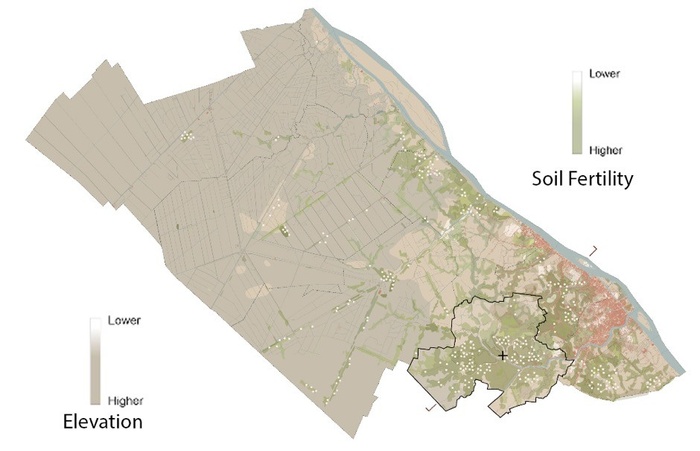

Rivers and canals deposit sediment on their banks creating natural levees. Our site, Phong Dien, lies in the upper alluvial plain where the fertile soil and the topographical construct of land makes it ideal for growing fruit.

Sediment Accumulation along Can Tho River

Sediment Accumulation Process

Phong Dien lies within the municipality of Can Tho and is a peripheral district of Can Tho City.

Soil Fertility in Can Tho Municipality

Agricultural Trade on Water

Cut and Fill Agriculture

Unsustainable Agricultural Export Practices

Pollution of Canals due to Pesticides and Unsustainable Packaging for Agricultural Export

Low-Tech Manually-Operated Sluice Gates

Monkey Bridge over an Aquaculture Pond as an Element of Eco-Tourism

60% of Phong Dien’s agricultural yield is fruit, and the rest is rice. One of the issues today is that rice paddies are being replaced by specialty fruit orchards, which make more money and decreases the soil quality. Reduction of rice fields decreases the water holding capacity of the soil in an already flood-prone area.

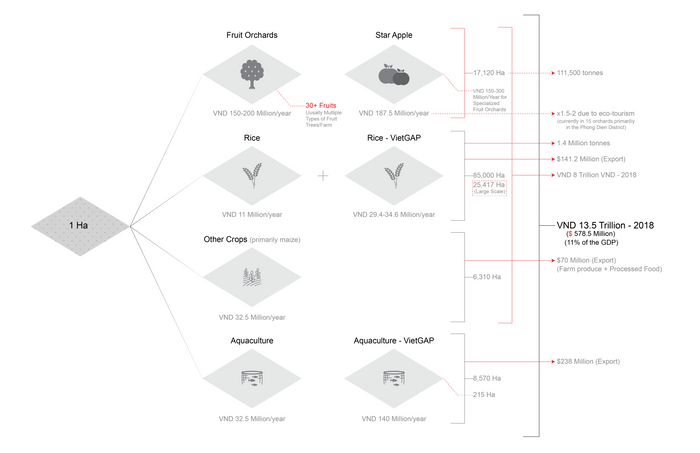

Agriculture in Phong Dien

From a purely economic perspective, agriculture has limited value, especially in the context of Vietnam’s growing industrial and service economy. The production and export of rice from the Mekong was once central to Vietnam’s economy. However, today, agriculture only accounts for 11% of Vietnam’s GDP.

Existing Agricultural Economy of Can Tho

But, it’s not fair to dismiss the other co-benefits agriculture offers. We need to start recognizing the ecologically, and socially resilient aspects of agriculture. Despite limited short-term economic value in the current moment, agriculture has long-lasting social, ecological and economic benefits.

Agriculture workers build deep social networks that sustain culture and help communities grow and adapt to change. Traditional practices in rice farming and aquaculture also effectively manage flood waters by using fields as holding basins. A naturally draining field also can help to recharge the aquifer and contribute to countering the gradual subsidence of the delta. Sustainable agriculture can also store carbon, purify water, regulate climate and provide essential habitat for birds, fish, insects and other wildlife. Finally, agriculture in or near cities has long term economic and social benefits because it can ensure food security in a globalized economy that will be facing greater disruptions with climate change.

Road Based Urbanization

Construction of new roads and road based urbanization poses an urgent challenge to farmers in the periphery of Can Tho. Roads like “Nguyễn Văn Cừ” are being extended outwards from Can Tho City to peripheral agricultural areas such as Phong Dien. This leads to the displacement of hundreds of farmers to remote parts of the district, and in many cases the loss of their livelihoods.

Erasure of Farmland

Nguyen Van Cu Extension

Nguyen Van Cu Extension

The Proposal

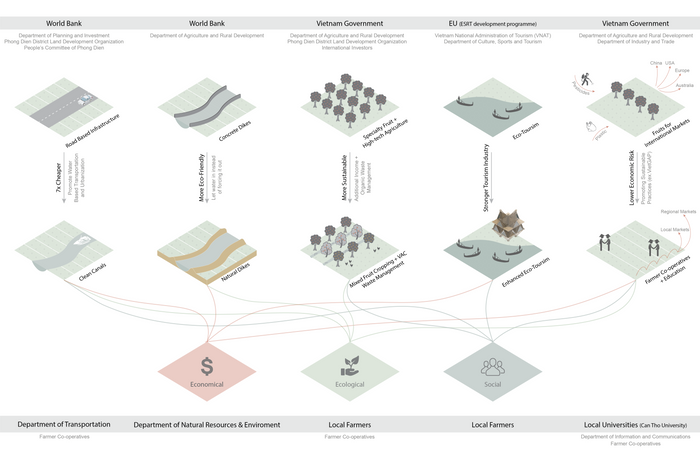

Redirecting Investments

This diagram explains possible stakeholders who would need to come together to re-think the future of Can Tho’s peripheral farmland.

Unsustainable land based to sustainable water based initiatives

The formation of cell-based farmer cooperatives is imperative as it would strengthen the argument against the construction of roads and the subsequent urbanization that follows. A cohesive organization would help to collectively push for an alternative canal-based growth pattern and coordinate better with Can Tho city officials.

Stages of New Urbanization

The intervention would start by creating service nodes at the confluence of rivers and canals. These would provide services for existing farmers, and act as an incentive for urban growth along canals. By reinforcing the idea of returning to canals, we incentivize the densification of urbanization along the canals to a limited extent, in a linear fashion. This would also help in the preservation of agriculture fields. What currently looks like patchy urban areas, becomes a full-fledged linear development zone that leverages the cell-like patterned landscape.

Creation of Service Nodes - Increase Urban Density along Canals - Collective Transport of Agricultural Produce

These nodes would first become community hubs for adjacent farmers’ cooperatives. They would eventually grow and harbor functions like manufacturing units, offices, piers, educational centers and community spaces to cater to the growing density of people.

Agricultural Cell Based Interventions

We propose the formation of cell-based farmer co-ops, to better the collective management of farms and the produce that would be transported to collection points at the service nodes mentioned above. By the introduction of multi-cropping and VAC systems (integrated agriculture, aquaculture and animal husbandry), we create a more economically, ecologically resilient agricultural system. This would be followed by the introduction of wetlands at the core of the larger cells, connected by linear wetlands. These linear wetlands would be created by taking up to 10% of adjacent plots so that all the farmer co-op cells are responsible for its maintenance.

Introduction of Multi-Cropping and VAC (middle ground), Wetlands (low ground) and Linear Wetlands

Section through the Intervention

To better understand the relationship of these interventions with the topography, we cut a section from Can Tho River to the innermost cell. The cells are formed by primary, secondary and tertiary canals. Within each cell – the center forms the lowest basin, which we convert to rice fields that act as water holding systems. The region along the canal forms the higher basin, which becomes the development zone. The highest density of urbanization is close to the primary canal, and it decreases as you go closer to the tertiary ones. The in-between zones continue to be orchards. A similar topographical pattern can be seen on the larger scale, where the ground is higher close to the primary canals, and lowest close to tertiary ones. In this case, the lower basin forms wetlands that add to the water holding system.

Section through the Intervention

Together, these interventions help to manage the water during floods and droughts.

Low-Tech Strategies Employed throughout the Agrarian Landscape

Linear Wetland

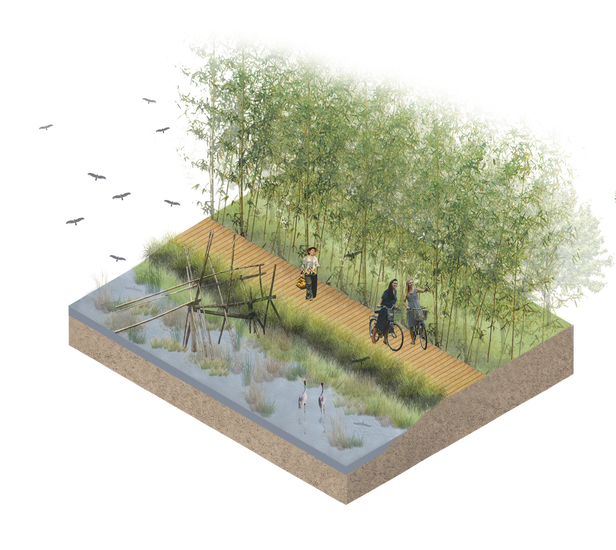

Bamboo plantations line linear wetlands that have boardwalks and monkey bridges to promote eco-tourism along with introduction of biodiversity.

Sluice Gates through Linear Wetlands - Dry Season

Sluice Gates through Linear Wetlands - Wet Season

Sluice Gates through Linear Wetlands

The sluice gates help manage the water during floods and droughts, while also purifying polluted water.

Multi-Cropping and VAC

This constructed ecosystem allows soil to be more fertile, while reducing farm waste that can be fed to poultry and fish in the ponds. Additionally, the ponds act as water holding systems.

Collection and Transfer Point

This service node is an important junction where agricultural produce is collected and transferred. Additionally, it is a food processing and storage point that also has a biomass plant to deal with waste.

Service Node Intervention

Road based urbanization along the “Nguyễn Văn Cừ” road stops at this junction, and creates an opportunity to transition from road to water based transportation, and urbanization. The buildings and linear wetlands both follow the existing agriculture plot lines. (Linear wetland/agriculture intervention, formulate a pattern based on agricultural plots.) The edges get transformed into a combination of wetlands and mangroves systems to create a natural buffer to prevent the construction of concrete dikes.

Intervention at Transition Point between Road and Water based Transport

Transporation Network

Commercial Zones

Bamboo Architectural Typologies of New Development

The bamboo grown along the linear wetlands is harvested, transferred to a mill at service nodes, and eventually used as a building material for the new buildings. Bamboo is used as the primary material as it is environmentally friendly and a flood-tolerant construction material.

Agricultural Produce Processing,Packaging and Storage Facility

Multi-Story Residential

Commercial/Hotel

Mixed-Use (Residential + Commercial)

Homestay

Education Institution

Observation Tower

Phasing

Phase 1

Phase 2

Phase 3

The new urban areas being built today may well be under water for much of the year by the middle of this century. There is an urgent need for new patterns of development. Those patterns that have best chance at successful adoption will be built on learning from the past and protecting what has worked over time.

We propose a new kind of city, where we invite urban growth within the agricultural landscape in a controlled manner. By blurring the lines between what is thought to be rural and urban, we form a city that protects the existing landscape which will become instrumental in adapting to climate change. This pilot concept is one attempt to show what such a future could be while also simultaneously considering the ecological, social, and economic consequences of development.

View from Agriculture Fields towards the new canal based development

6

New Energy Landscape

Students: Angela Crisostomo, Peiqing Wang, Bohong Zhang, Wenjun Zhang

What if a new energy landscape can form socio-ecological exchange systems in Can Tho?

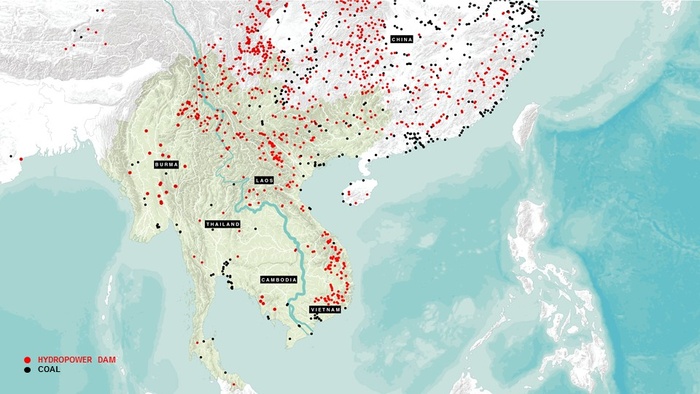

Existing and Proposed Dams and Coal Power plants across the Mekong Delta up to Year 2050.

The Mekong Delta is in crisis. As of today, there are 364 Hydropower Dams and 30 Coal Plants, existing and planned along the Mekong River and its tributaries. Vietnam’s energy landscape today is mostly supplied by hydropower and coal relying heavily on foreign investment and imports.

These energy infrastructures, planned at regional scales to supply the growth of industrial and urban centers, have significant environmental and social impacts at local resolutions – especially in the city of Can Tho where the upstream consequences of hydropower dams have a direct impact on the lives, livelihoods, and culture of communities dependent on the health of the Mekong River and its tributaries.

Lower Sesan Dam in Stung Treng Province, Cambodia.

Together with the Sambor Dam, the Stung Treng Dam has the Mekong River Basin’s highest sediment trapping efficiencies in the Lower Mekong Basin. The dam has displaced 1,500 households; negatively impacted agricultural productivity and livelihoods downstream; and wholly impeded fish and river dolphin migration routes.

Local Fish Market in Stung Treng Province, Cambodia.

Fisheries and agricultural productivity in the Mekong Delta are dependent on the delivery of sediment from the Mekong River, which upstream hydro power projects disrupt.

River side Market in Cai Rang District, Can Tho, Vietnam.

At risk are the extremely fertile landscapes of the Lower Mekong Delta. In Can tho, farmers can harvest up to seven rice crops every two years. Cassava, sugar cane, soybean, and maize can also be planted in abundance. Veggies and fruits earn the best profits per hectare for local farmers.

Floating Market at Cai Rang District, Can Tho, Vietnam.

In Can Tho, commerce at the floating market start as early as 5 am. Water is still very much a part of the culture, and still acts as vital infrastructure both at the waterfront and in inland rural areas.

Sluice Gate in Phong Dien District, Can Tho, Vietnam.

In Can Tho, canals and tributaries are appropriated by communities and families for various domestic, industrial, and agricultural uses.

Our project explores how Can Tho’s energy landscape can shift – from a dependence on hydropower dams and coal power – to localized, low-carbon industries of waste-to-energy and solar power, phyto-remediation, and water treatment; preserving the health and livelihood of local residents and leapfrogging decades of environmental degradation.

Project Introduction Video

Impacts of Centralized Energy Infrastructure

Can Tho’s Binh Thuy District, is an area being primed for development as a gateway for the proposed Ho Chi Minh - Can Tho Expressway based on the City’s 2030 Masterplan. The proposal expands industrial development along the Hau River - South of the O Mon Coal Power Plant, and creates a commercial center in former agri-residential areas.

Proposed 2030 Landuse Plan for Binh Thuy District, Can Tho.

Existing conditions along the Hau River, Can Tho, Vietnam.

The strict Euclidean zoning of this road-based plan places greater demands on the social and ecological systems of the district – as large swaths of land along the waterfront become privatized for single-use industrial, commercial, and residential developments; existing communities and livelihoods are displaced; and along with them, cultures of living and working with water and natural systems.

Energy Exchange Sheds: A New Pattern of Development

Our project is a critique of fossil fuel-based energy infrastructure which follow grid like patterns of development. Centralized models of privatized extraction, production, and distribution spread across the landscape – overwriting existing urban, cultural, and ecological fabrics. But what if we can break this system into its components and develop a new pattern of inclusive urban rural development from the nexus of energy, waste, and water?

Energy Exchange Shed Development Strategy.

Energy exchange sheds are sites where localized energy is produced and distributed at a neighborhood scale. The infrastructure of these energy exchange sheds incorporate water treatment and storage, waste management, and energy production systems designed based on traditional knowledge and natural systems.

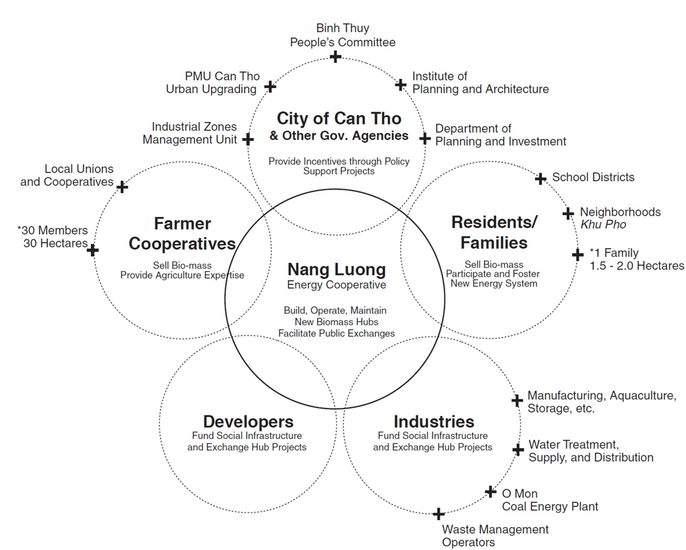

Our strategy is to develop energy exchange sheds around existing sites of social exchange - what we call anchor institutions. It begins with the formation of energy cooperatives (called “Nang Luong” Cooperatives) joined by local residents and families, farmer cooperatives, local industries, local government, and private developers that act together to build, operate, and maintain new energy infrastructure.

We envision that these energy exchange sheds would multiply, serving smaller areas, but expanding across the landscape to form networks of public spaces that foster a stronger relationship with existing water systems (rivers, tributaries, canals).

Nang Luong Energy Exchange Cooperative Stakeholder Diagram.

The boundaries of energy exchange sheds are determined by the reach of anchor institutions. As opposed to a centralized approach, this model fosters an incremental transition to self-sufficiency by easing the burden on centralized systems while improving existing social infrastructure - promoting systems of cooperation, public exchange, and political empowerment.

Thru this model, water treatment and storage, waste management, and energy production systems integrate to support a given population density that develop gradually to match the needs of its shed building social and ecological capital.

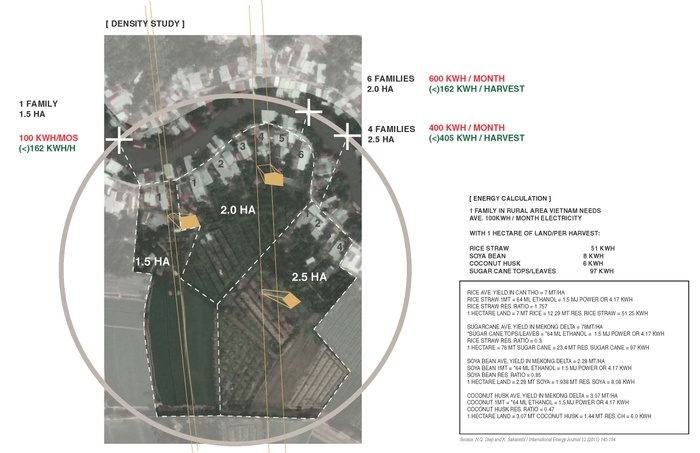

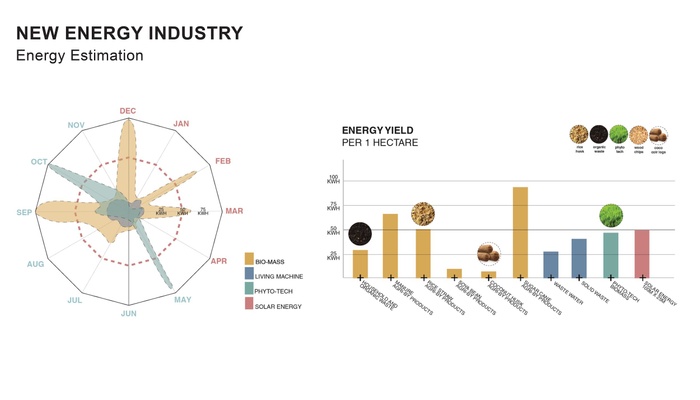

Biomass Energy Calculations and Density Strategy.

Energy exchange sheds utilize the potential of waste and agricultural byproducts within a given area, supplementing the remaining demand with solar power. Balancing the demand for energy and the supply of biomass entails creating productive landscapes which the Nang Luong Cooperative would undertake. Residents and farmer cooperatives sell waste and agriculture byproducts of rice, soya bean, coconuts, and sugar cane; finding new ways to make more productive landscapes and balance their energy usage.

Developers and industries who wish to create new land-uses within the energy shed would be incentivized to invest in waste-to-energy, water treatment and supply, and phytoremediation infrastructure - working with anchor institutions to upgrade existing social infrastructure.

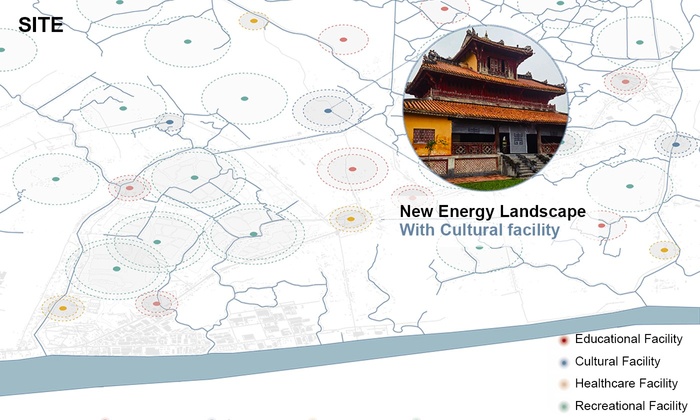

Cultural Energy Exchange Sheds

Anchor institutions (whether private or public) often provide local employment, essential public services, and often already have support networks that can be better engaged in changing the surrounding urban fabric. We identified four types of anchor institutions that would work well as Energy exchange sheds: Educational, Cultural, Healthcare, and Recreational.

The Van Thoi Tu Pagoda as a Cultural Anchor Institution.

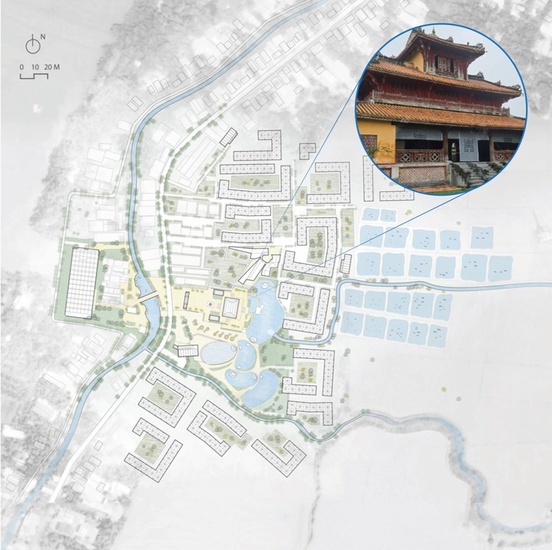

As a prototype, we focused our design on a Cultural anchor institution – the Van Thoi Tu Pagoda in South Tra-An located at the confluence of a river and a canal. Here, new residential development around the Pagoda (former agricultural land-uses) develop hand in hand with water supply and treatment infrastructure (Living Machines), Phyto-technologies which clean the water, land, and air; and New Energy Infrastructure (Biomass + Solar).

Proposed Site Development.

Ritual Processes

Vietnamese Pagoda’s are sites of ritual processes related to culture, history, and spiritual transformation. In Vietnam, the pagoda is not only a place of worship for the Buddha, but also legends, heroes, and ancestors. Present in many neighborhoods and often situated near canals or waterbodies – people gather inside the pagoda to meditate on the past, present, and future, wishing good health and fortune on family, friends, and community; outside the pagoda, plazas host traditional village festivals; and markets (which emerge from rivers) cater to pagoda-goers.

Neighborhood Courtyards and Community Center.

We imagine expanding these ritual processes on a neighborhood scale - incorporating new development and energy infrastructure within the Pagoda and its surrounds, creating new ritual processes for water treatment, phyto-remediation, and waste management.

New public spaces and infrastructure across the Pagoda include a biomass processing facility, fish market, floating market, and boat charging stations.

Around the pagoda, biomass from waste, agricultural products, and phyto-remediation technology can be utilized at both a domestic and neighborhood scale. Organic waste drop-off sites can be integrated in new community centers supplemented with solar panels that assist in both collecting materials and generating energy. These community centers located at the heart of new neighborhoods can provide spaces for local residents to organize and manage community projects.

Three Integrated Systems

Three integrated systems of the energy exchange shed include Living Machines, Phyto-remediation Technology, and New Energy Industries.

Living Machines

Living machines are water treatment and supply systems integrated in recreational areas and public spaces. They begin at existing rivers and tributaries, connecting these to new surface water wetlands and pools which act as basic filtering. Once treated, water is then stored in water tanks as water supply for both domestic and agricultural use. All organic waste collected in this process can also be used as biomass fuel.

Living Machine Systems Diagram.

Three filteration ponds retain and treat surface water with phyto-technology, allowing slow recharge of aquifers.

Living Machine Systems Diagram.

Behind the Pagoda, clean water can be utilized for recreation and ritual.

Living Machine Systems Diagram.

Anaerobic, anoxic, and aerobic reactors are scattered throughout the landscape to ensure potable water for domestic use.

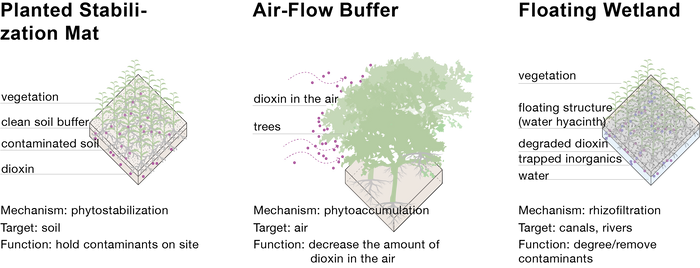

Phyto-remediation Technology

Planted Stabilization Mats, Air-Flow Buffers and Floating Wetlands are three approaches of Phytoremediation Technology which are aimed at the absorption of dioxin in the soil, air, and waterbodies of the neighborhood.

Phyto-technology toolkit.

Phyto technologies are employed all year round with different kinds of plants to ensure a continuous purifying process. Once the plants become mature and have maximized their capacity for dioxin absorption, local residents can transport the plants to the nearby energy boiler by electric motorbike or electric boat via canals to for power generation.

Phyto-technology as biomass for New Energy Industries.

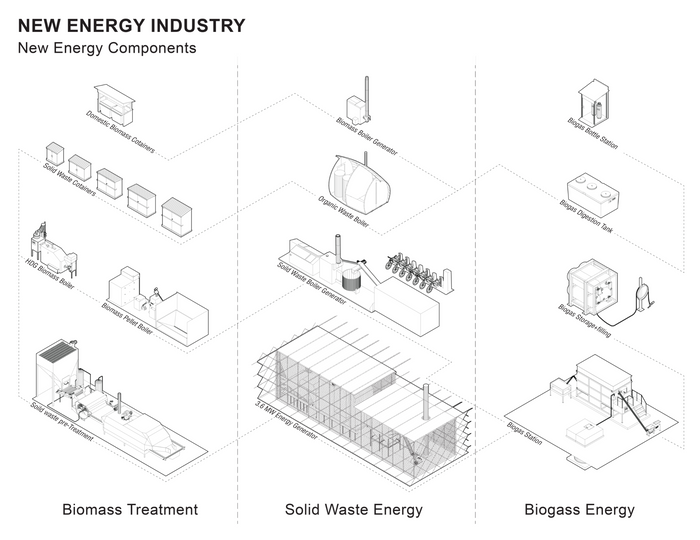

New Energy Industries

New energy industries utilize waste to energy and solar technologies. Components of waste to energy consist of solid waste treatment, biomass processing, and biogas energy.

Used plants from living machines, as well as by products from community and domestic phyto-technology programs are harvested and sent to our biomass energy plant to process contamination and generate energy.

Decentralized New Energy Infrastructure Components.

The system incorporates an internal feedstock exchange loop in which waste is treated and processed in domestic and community facilities before being processed for energy in biomass plants. Components of the system have different sizes to satisfy different scenarios from small biomass boilers for households to a biomass energy plants for whole neighborhoods.

Energy Potential Calculations per crop and by season.

Because there are up and down times for the supply of feedstock, solar panels are adapted into the system to fill gaps during low feedstock supplies in order to maintain year-round operations.

Conclusion

In a landscape where entire communities, traditional livelihoods, and local industries are being displaced, we re-think the nexus of energy, water, and waste infrastructure to propose a new pattern of development centered on building traditional knowledge and natural systems. Working with existing land-uses and cultural fabric; we see energy exchange as a powerful design strategy to create new patterns of vernacular development in a transitional landscape.

Aerial Perspective at Van Thoi Tu Pagoda, Can Tho.

7

Amphibious Can Tho

Students: Amanpreet Duggal, David Mauricio, Gabriel Vergara

What if the edges of rivers and canals in Can Tho are reimagined as territories of transition between land and water that can adapt to the seasonal flux of the Mekong?

From a hard edge to a territory harboring an amphibious community

Project Introduction Video

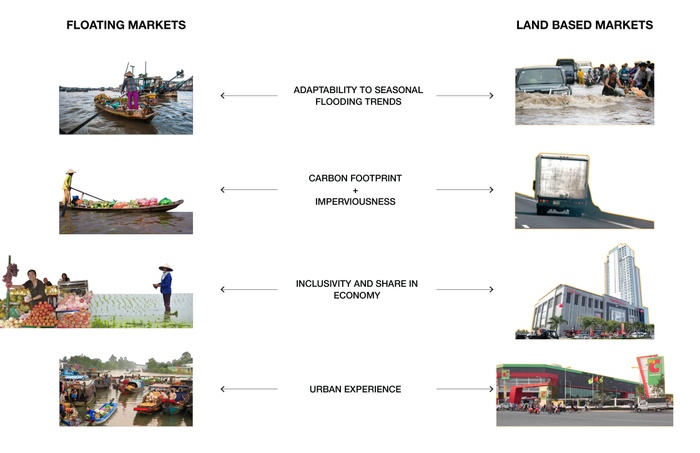

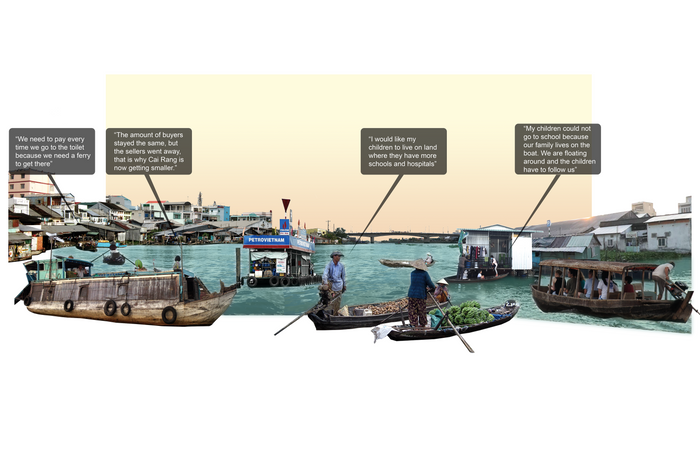

The lower Mekong region of Vietnam is vulnerable to economic disruptions due to flooding. According to World Bank Report in 2014, Can Tho city of lower Mekong floods on an average of twice a day during the wet season. This figure is expected to increase greatly as the inundation of main roads is projected to rise to a staggering 270 days per year by 2030, leading to severe losses for land-based markets. The floating markets, on the other hand, continue to function during floods and have evolved various ways to adapt to fluctuations in water levels. What can be learned from floating markets and their adaptable social and economic models, to re-imagine a resilient future for Can Tho and the entire Mekong Delta?

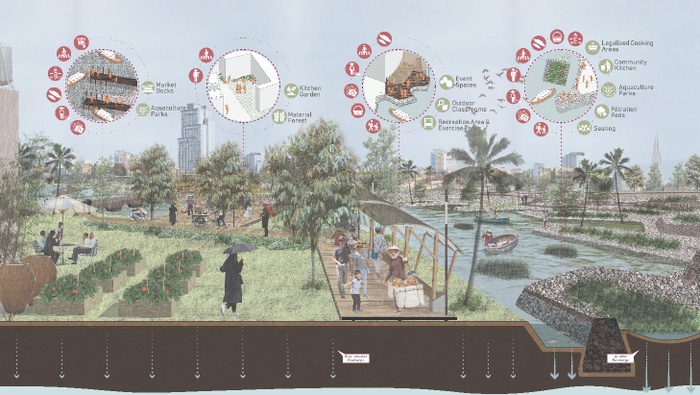

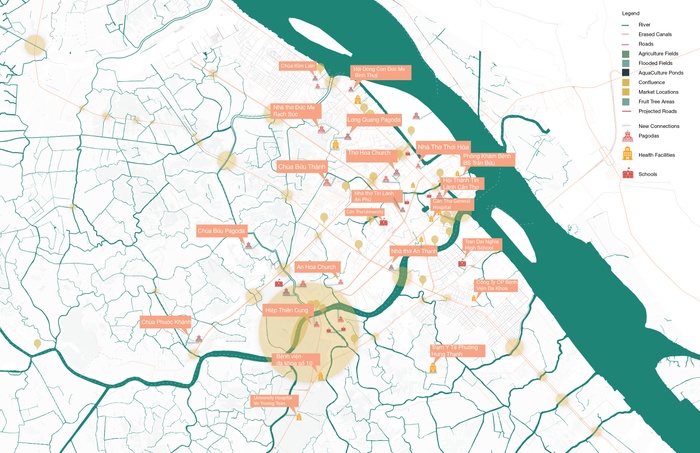

The project proposes reimagining the edges of the floating market in Can Tho as territories of transition between land and water where the two synthesize to create an adaptable settlement for an amphibious community. These transition zones will be anchored around important riverine confluences and social institutions of the city that will be connected to waterways. Through the creation of inlets, social services will become more accessible to the floating communities.

As an amphibious community both socially and economically resilient to flooding and the cascading impacts of climate change, the floating market communities will hold the key to the resilient future of the city. The implementation of this amphibious and dynamic edge adaptation will begin by empowering a marginalized population that possesses the invaluable traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) of ‘living with water’.

Amphibious living: Floating houseboat in the Cai Rang floating market

Amphibious living: A vendor in the floating market

Amphibious living: Early morning activity in the floating market

Amphibious living: Floating restaurant

Amphibious living: A student leaving for school from his floating house

Amphibious living: Le Binh market adjacent to the Cai Rang floating market

Floating Economies in the Mekong Delta

For centuries, floating markets have served as the local condensers of social and commercial activity in the Mekong Delta region. In the past, the Mekong Delta had dozens of floating markets supporting daily life. Presently, there are only 11 functioning floating markets in the region. These functioning markets face the constant threat of losing their local significance and being reduced to tourist attractions due to the preference for a land-based lifestyle.

Floating markets in the Mekong Delta region

The current governmental policies favor land-based development as opposed to the traditional water-based way of life. This is apparent in the proliferation of the road network and the depletion of the water transportation network.

From water-based to land-based infrastructure: Increase in the road network

From water-based to land-based infrastructure: Erasure of canals

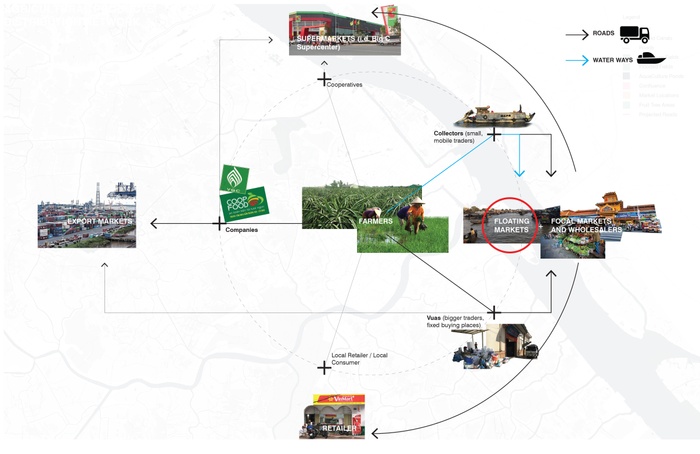

The population served by the floating markets is also reducing due to their diminishing importance in the food distribution cycle and their inability to compete with the efficiency of chain stores and land-based markets. The markets only serve a small base of local wholesale buyers and have no link to the export industry.

Position of floating markets in the food distribution cycle

It is therefore essential to realize that with the loss of floating markets, Vietnam stands to lose the several functional benefits these markets can serve in term of social, economic and environmental resilience. They offer significant benefits when compared to land-based markets that will become imperative as the number of inundated days continues to grow.

Learning from floating markets

The Cai Rang Floating Market of Can Tho

The Cai Rang floating market of Can Tho faces similar threats and has decreased from 550 boats in 2005 to 300 in 2017(source: Hindustan Times,2017). Lack of access to educational institutions, healthcare, and sanitation facilities forces the sellers to move to land in search of a more comfortable lifestyle.

Issues on the ground

Physical inaccessibility to the water edge and government policies of building embankments and dikes is further destroying the relationship between land and water and leading to a smaller customer base.

Images of threats to the Cai Rang floating market: One Way Transfer of Goods-Warehouses

Images of threats to the Cai Rang floating market: One Way Transfer of Goods-Road System

Images of threats to the Cai Rang floating market: Lack of Water Access-Narrow Passages

Images of threats to the Cai Rang floating market: Lack of Water Access-Small Pedestrian Bridges

Images of threats to the Cai Rang floating market: Flood Protection Walls

Images of threats to the Cai Rang floating market: Land-Based Market and Solid Embankment

Maps of threats: One-way transfer of goods from water to land

Maps of threats: Lack of physical access to social services

Maps of threats: Embankments and seasonal flooding

Bringing ‘Value’ Back to the River

The design strategy aims to counter these threats by reimagining the river and its edges as areas for concentration of social, commercial and cultural activity making it the major spine of the city. To achieve this, we make strategic connections from the river to the important institutions of the city making them accessible by water and the anchors for densification. Establishing a water-based energy production system will promote a sustainable alternative to land-based non-renewable sources. Reimagining these edges as socio-ecological places for exchange that adapt and shift with rising water levels will help make the city environmentally resilient and create places for the floating market to replicate enabling a shared and inclusive economy.

Strategies for bringing ‘value’ back to the rivers

Strategies for bringing ‘value’ back to the rivers

Strategies for bringing ‘value’ back to the rivers

The existing bridges that lie at the confluence of road and water transportation system can be re-imagined as energy hubs that serve vehicles on both land and water making them the amphibious ‘gas stations’ of the future.

Bridges as amphibious energy infrastructures

*From Anchor to Floating

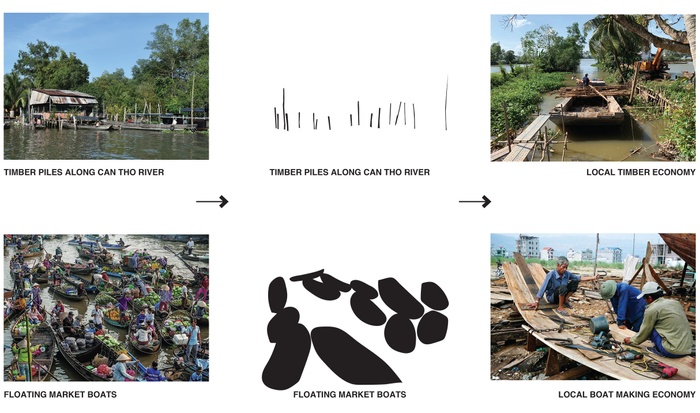

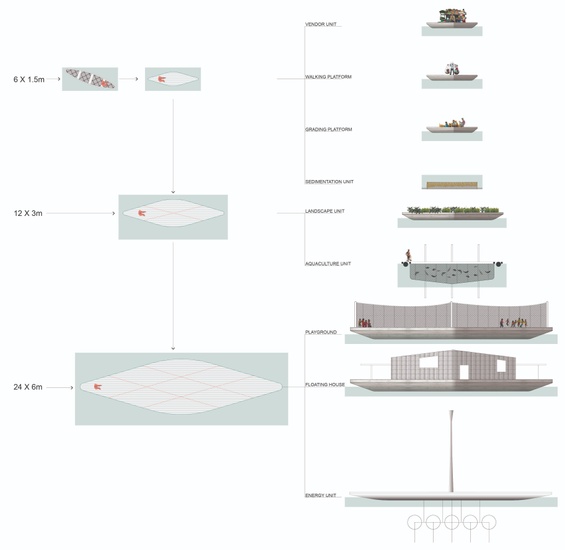

To implement these strategies, we looked at the existing material systems at play in the market that range from elements that are fixed such as timber piles to elements that are floating such as boats and floating houses. These systems are supported by the use of local resources and the indigenous boat making industry.

From ‘Anchor’ to ‘Floating’

Learning from these systems, we evolved a ‘buoyant unit’ that is derived from the size of a regular boat in the market. This unit can be scaled up to allow for multiple functions on the floating market site and are specific strategies for this particular site.

Taxonomy of ‘Buoyant Units’

These ‘buoyant units’ can help transition the edge from a hard line to a more adaptable territory that shifts with the temporal flux of the river.

Evolving the edge to an adaptable region. Transition Moment 0: Soft Edges Before 2012

Evolving the edge to an adaptable region. Transition Moment 1: Solid Embankments and Flood Walls

Evolving the edge to an adaptable region. Transition Moment 2: Flood Events

Evolving the edge to an adaptable region. Transition Moment 3: Timber Piles and Regrading Embankments

Evolving the edge to an adaptable region. Transition Moment 4: ‘Bouyant’ Units

Evolving the edge to an adaptable region. Transition Moment 5: Social Performance

Creating an Amphibious System

The design is the generation of a system that is essentially incremental and self-built. For the pilot implementation of this system, we looked at the site adjacent to the floating market where the building of an embankment has disrupted the relationship between land and water. The gradual transition of this site in phases aims to re-establish this relationship and create an inlet to the educational institution inland. The site will eventually evolve to a node in the robust water transportation network and will act as an anchor for this mobile infrastructure.

Transitional edge connecting social services with waterways

Transitional edge connecting social services with waterways

Transitional edge connecting social services with waterways

The inlet or ‘Xanh’scape will involve a number of stakeholders that will gain value by becoming adaptable to shifting water levels.

Stakeholders through the ‘Xanh’scape (linkage from water to inland institution)

Stakeholders through the ‘Xanh’scape (linkage from water to inland institution)

The amphibious zone will be perennially vibrant, environmentally sustainable and will cater to local practices and way of life.

A moment in the amphibious zone

The amphibious system can eventually be replicated around the city and region at important confluences and civic institutions to form a network of amphibious communities.

Replicability along rivers and canals in Can Tho

Aerial View of the site

In the future, as inundation becomes increasingly frequent due to land subsidence and sea level rise, the Mekong Delta will need solutions that operate in both regular and flooded conditions. By adopting this system, we can create a network of amphibious communities that help the city develop social, economic and environmental resilience and create a local model of adaptation that addresses the global threat of climate change.

Afterword

Changing Perceptions: Resilience in Practice