Foreword

Mula Mutha: Living River as Next Century Infrastructure

“Water is life. It’s the briny broth of our origins, the pounding circulatory system of the world…” (Barbara Kingsolver “Fresh Water,” 2010)

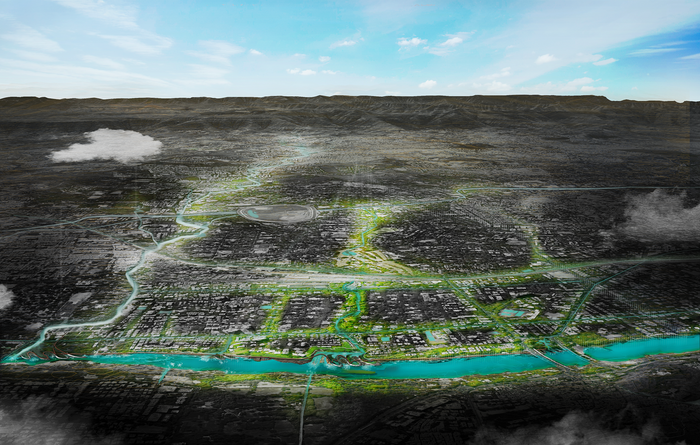

How can water and urbanism be considered together as a generative frame for resilient cities of the future? How can urban design practice emerge from a rich synthesis of social life and ecological regeneration strategies? Water in its many forms underlies the future of Pune. It is constantly in motion, changing states, moving waste, crossing borders, nourishing (and destroying) life. A mega-project titled “Pune Riverfront Development” to straighten its edges, dredge, blast and remove the basalt topography of the Mula-Mutha River and concretize its banks is on the boards for the Pune Municipal Corporation with the aim of flood protection and beautification. Our studio questioned this approach, and aimed to offer an alternative vision to this which does not replicate the mistakes of past decades (in places such as at the Los Angeles River, and the Sabarmati in Ahmedabad) and advance phased approach to transformation that builds from the principle of embracing the Mula Mutha as a living river and leveraging social infrastructure, strategic edge access, ritual and ecosystem restoration to meet its potential as a green-blue center of Pune.

Introduction

Pune and the Mula-Mutha

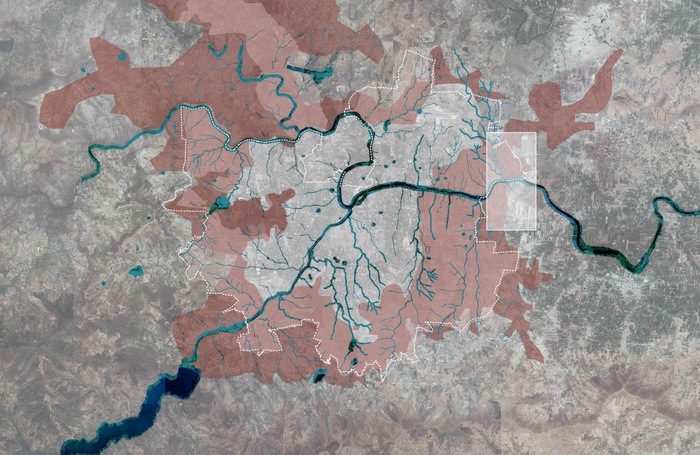

Pune City sits at the confluence of the Mula and Mutha rivers in the foothills of the Western Ghats, one of the most bio-diverse regions in India. Pune was the center of the Maratha empire in the 18th Century, and continued to grow in the 19th and 20th under British colonial rule and later as an educational as a hub central to India’s emerging global leadership in technology and education. One of the largest cities in India, Pune has expanded at a staggering rate since the liberalization of the Indian economy in the last 30 years, from 5,427 hectares in 1991 to 45,944 in 2011. This expansion is only accelerating, even as growing social and environmental instability is emerging due to climate change. Regional droughts, which are becoming more common in Western India, have accelerated the inmigration of farmers seeking seasonal employment in Pune, which has led to a shortage of affordable housing and the proliferation of slums along the Mula-Mutha River. As many as two million people—and rising—live in Pune’s slums, which has in turn put immense pressure on the City’s water resources and civic infrastructure. Water storage and sewage treatment facilities in Pune are limited and aging; they are neither capable of bearing the weight of increased flood risk, nor are they up to the task of serving a growing and expanding population.

To address these stresses, the Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC) has undertaken a comprehensive resilience strategy that aims to guide integrated and equitable growth, mainstreaming climate action and resource management, and strengthening economic and workforce capabilities in Pune. One of the many initiatives proposed in the Resilience Strategy is the Mula-Mutha River Conservation and Riverfront Project. The project aims to address river pollution from solid waste and sewage, mitigate water depletion from upstream dams, and improve public access to the waterfront. Nevertheless, it has been critiqued by community and environmental groups for its drastic concretization and commercialization of the riverbanks, and for the unwanted destruction of native rock formations and wildlife habitat. It is also encountering significant implementation barriers, owing to complex jurisdictional ownership and management framework. Moreover, the project does not currently address informal settlements on the River or coordinate with the construction of six new sewage treatment plants, currently being planned by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). There are also concerns with coordination action between Pune’s planned 3 line metro system, much of which is being built as an elevated structure along the River. This transit project is a national priority and will hasten development under existing laws that mandate upzoning near transit. Mobility and housing affordability are rightly priorities; but coordination of these three mega-initiatives is essential for their mutual success for improving life for Pune’s growing population. And increasing water consumption, rapid development of upstream areas, rural versus urban water needs, and pollution all speak to the larger, more systemic scale of vision and coordination required to implement transformation of the river system.

Columbia’s Spring 2019 Urban Design Studio, in partnership with 100 Resilient Cities and the Center for Resilient Cities and Landscapes, took a second look at the Mula-Mutha River Conservation and Riverfront Project, and proposed alternatives to the current proposal that attempt to address the systemic ecological and social challenges that Pune faces. The team visited Pune in January 2019 to meet with representatives of the PMC and collaborate with students and faculty from the Bharati Vidyapeeth Institute of Environment Education and Research (BVIEER) department of environmental management and the College of Engineering Pune (COEP) department of Urban Planning.

While in Pune, the Columbia studio developed 10 urban design principles, which guided student work throughout the duration of the semester. The projects presented here explore new paradigms for river revitalization, ecological conservation, and community empowerment. They attempt a more expansive long view of riverine health and urban development as interlocking systems best served by nature-based solutions, sustainable and equitable management practices, and programmatic stewardship. Taken as a whole, they promote a vision of Pune’s future as a city guided by principles of environmental responsibility, social equality and public safety—a model of responsible urban growth for cities throughout South Asia.

Principles

Ten Principles for a Resilient Pune

Essay

THE MULA MUTHA OVER TIME

Historic painting of the Mula-Mutha

Basalt outcropping and bird sanctuary

Mixed urban and rural character of the Mula Mutha

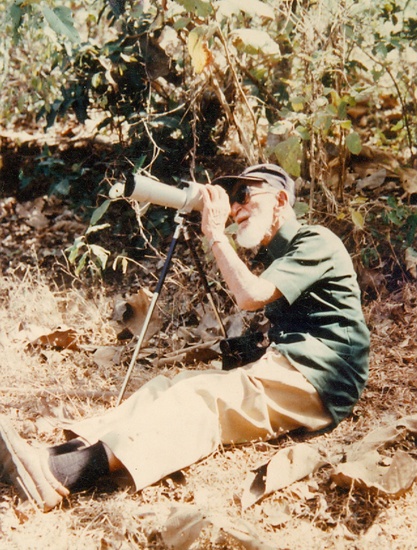

At the Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary with Dr. Barucha

At the Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary with Dr. Barucha

New metro under construction along the riverbanks

New metro under construction along the riverbanks

Ritual along the riverbanks

Water hyacinth invasion at the confluence of the Mula and Mutha

Historic fabric in Pune

Courtyard urbanism in Pune

Gathering along the riverbanks

1

HYPER MAIDAN

Students: PeiJou Shih, Zilu He, Donghanyu An

What if natural and social infrastructure systems are integrated in time and scale?

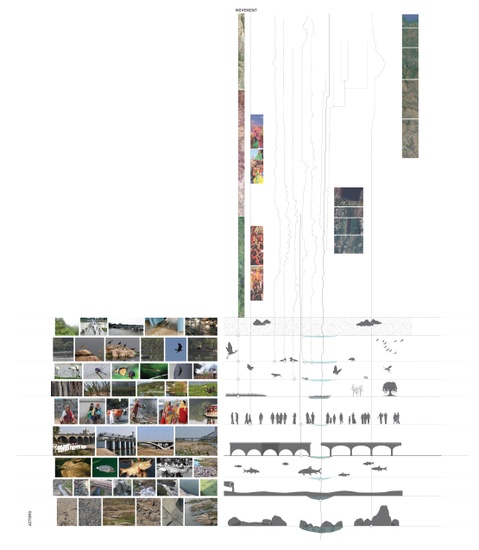

The hyper maidan is a system of interlocking systems and occupancies in space. It builds on the idea of the maidan, a common ground in Indian cities where everyone and everything is welcome. We use the concept of the hyper maidan as a resilient strategy for Pune, a city that is currently implementing a plan for the Mula-Mutha River that promotes fragmentation of land uses, isolated systems, and mono-occupancy of land and river. Our proposal blends land and river in a hyper maidan that interlocks systems, encourages temporal occupancies, promotes multiple uses, and operates at multiple scales toward the equitability of water, people, fauna and flora.

Project Introduction Video

Current Fragmented Systems Sabotage the Fullness of the Maidan

Development in Pune has fragmented land into small pieces for easier control, resulting in the loss of the city’s ability to accommodate the monsoon rains and the increase in population. The consequences can be catastrophic. On July 12, 1961, the Panshet dam built on the upstream of the Mutha river burst and the flood resulted in more than 10,000 families becoming homeless. But the consequences can also have an everyday impact such as on the sewage treatment system that is overwhelmed and underperforms.

It is necessary to learn from history and carefully rethink current infrastructure projects to make them as resilient and multi-functional as possible. We also see the need to consider ecological infrastructure alongside hard infrastructure.

We see ten systems operating in isolated and inefficient ways in Pune—Informal Settlement, River/rain, Ecology, Playground, Sewage Treatment, education, city-level transportation, regional rail, agriculture, and ritual.

Fragmented infrastructure is inefficient.

Translating the Maidan Concept into the Interlocking Systems Infrastructure - Hyper Maidan

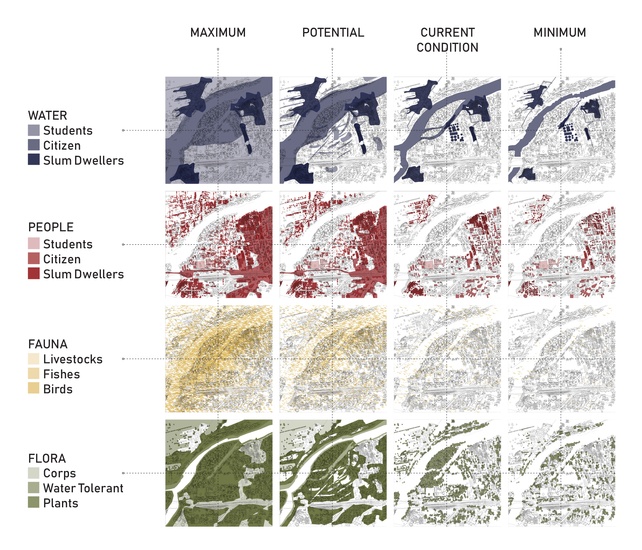

Systems Interlocking in Time and Scale We design for four stakeholders of the city of Pune: water, people, fauna, and flora. Each stakeholder is a seasonal occupier of the hyper maidan. We maximize efficiency by negotiating each of their occupations on a timely basis.

Temporal Occupancy by Four Stakeholders

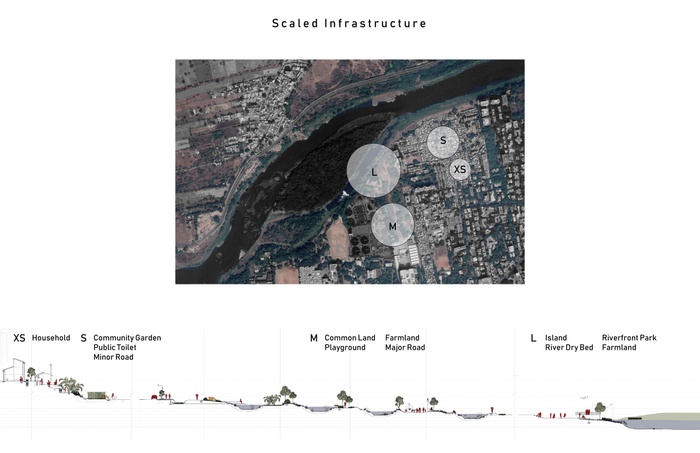

Systems Interlocking in Time and Scale We design at four scales: XS, S, M, L, and XL. Each scale accommodates a system in a different mutually supportive way.

The Design of the Interlocking Systems Infrastructure

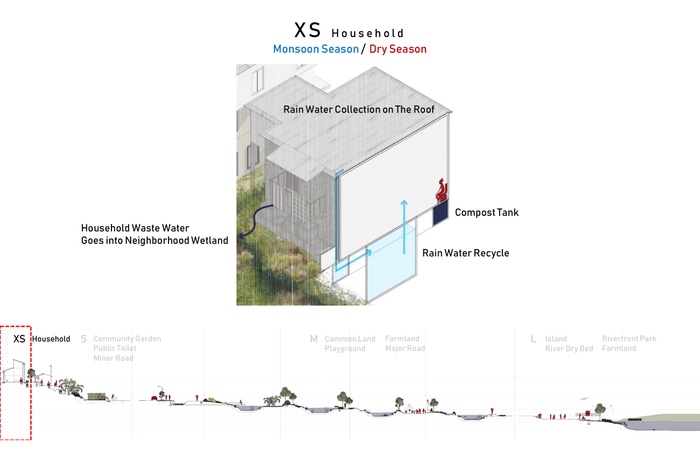

At the extra small and small scale, the household unit separates solid and liquid waste, collects rainwater in the monsoon season, and uses dry land for common activities in the dry season.

At a medium scale, ponds are used to hold rain and prevent flood in the city, treat wastewater, and grow plants including mosquito repellent plants, and animals, especially fish. In the dry season, festival and events can be accommodated.

At a large scale, we design a Bio-Park that gives room to the river, rain, and plants in the monsoon season while giving the room people and animals in the dry season.

Implementing Hyper Maidan in Different Scales on Site

Hyper Maidan Application XS and S scale in the informal settlement, M scale in open common ground. And L in the riverfront.

Site Plan in the Dry and Monsoon Season

Strategy Design in Scale At the small and extra small scale, people collect rainwater from the roof and separate solid waste for composting. They use the community size wetland to hold water in monsoon season and the land to gather in the dry season.

At the medium scale, during the monsoon season, the ground is used for growing crops and the pond is ready for fish when there is enough water. When the water goes down in the dry season, the land can be used for people and animals again.

The elements in a hyper maidan are worked together harmonious and efficient manner. The water full of the ponds and plants flourishing. while in the dry season, human and animal occupied the site.

Master Plan V.S. Space Temporal Occupancy

In the Hyper Maidan, the land is no longer segregated by the land use. Instead, it is redefined by the dynamic occupancy of people, flora, fauna, and water.

Space Temporal Occupancy

Space Temporal Occupancy

Hyper Maidan Network Implementation

The entire city can be a hyper Maidan over time, apply the time and scale strategy based on the analysis of topography and water flow.

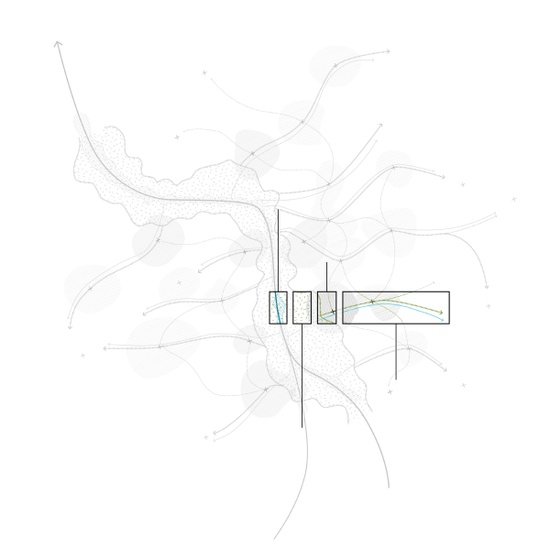

Based on Topography and Water flow

Infrastructure Network on Site

Infrastructure Network Implement to Entire City

Conclusion

The Hyper Maidan integrates systems in time and scale with infrastructure that provides more opportunities for not just people, but also plants, animals and water. We believe that Hyper Maidan is a paradigm for the resilient city of the future.

2

NATURE LED CBD

Students: Yanli Zhao, Yinzhe Zhang, Huiwon Hong

What if ecological and social resilience are the main drivers for developing a new CBD for Pune?

Nature led development during monsoon and dry season

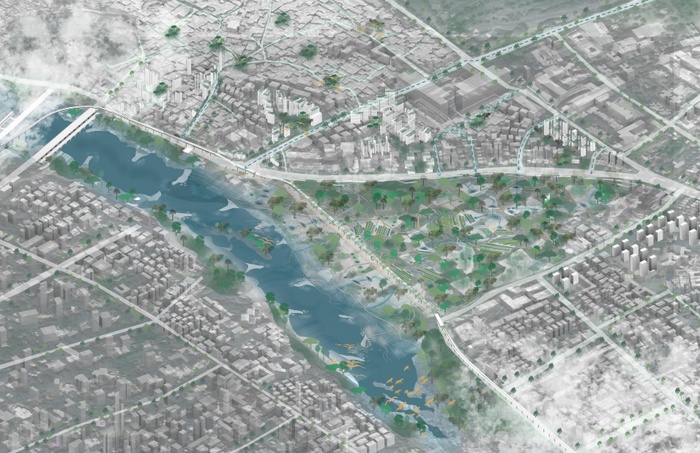

Our site is a peninsular at the confluence of Mula and Mutha River. We suggest a design strategy by which ecology is valued as much as economy. After considering the contours of the site we identify three floodable zones. Here, we propose fields, water tanks, and wooded areas along with a corresponding context for each. By localizing these three major landscape infrastructure strategies through the design of terraces, bunds and contour trenches, we create a new ground for high density development that includes Pune’s natural ecology.

Project Introduction Video

Will CBD be the only option for the island?

While Pune’s periphery has experienced rapid development, our site at the center of Pune has remained as agriculture area for the last 30 years. The Kirkee Cantonment, located to the north of the site, and the river circumscribes it on the west, south and east, have isolated the site from the rest of the city. However, in 2002, a bridge across the river and in 2005, the BRT road were built, bringing the potential of development. With the new metro lines and Pune Junction in the vicinity, the site can be expected to become prime property.

context of Pune city and potential development area

transit network

land value around the site

Our site has a potential role as a connector of dispersed development of Pune as BRT line is going through the site and metro lines are going to be built around the site, also land value is the trend to be more friendly here.

Site photo: Pune IT park

Site photo: Pune BRT route

Site photo: Sangamwadi Bridge

Site photo: Buildings under construction

Based on these trends, this new site can have various possibility.

similar scale development around the world

To see how the new development could look like, we compared the site with other cities with similar physical conditions but different fabrics. We chose Rome, new York, Shanghai.

city’s land use plan and a smart city proposal

One example of the 2040 Pune CBD imagined by an architecture company. Their major assertion was high-density development to stop urban sprawl and protect nature outside of the city. But it did not take into consideration Pune’s flooding and water pollution issue, or its endangered ecosystem. Another thing that was overlooked was the multi-functionality of the river.

flooding

water pollution

endangered ecosystem

multi-functionality of river

What if nature can lead development ?

The typical development approach is to flatten the site and edge it with wide roads. We suggest an alternate ecological approach led by landscape infrastructures, including terraces, bunds and, contour trenches.

Design phases

Starting with the contour lines, we defined the low, middle, and high ground areas. To provide a floodable area for the river during monsoon season, the low ground has been designed to become three eco areas that consist of different water holding strategies.

three major landscape strategies: terrace, bund, contour trench

various strategies applied on sites

We designed each site by carving the ground based on existing topography with the mentioned strategies.

Design Details

The three landscape infrastructures of terraces, bunds, and contour trenches have been localized to preserve and enhance the ecology of this site. Within each of three areas, we combine these infrastructures to increase water holding capacity. The existing BRT line and current context of each of the three areas are considered to develop a localized and eco-friendly design.

eco area one: contour trench

temple, maidans are located here to provide multi-functions for the site

The first eco area is located near the island which has remained as a forest for decades, in order to create a green corridor across the river, we implement wooded area strategies as the major focus for this site.

perspective view from the BRT station toward the riverfront

Eco area two: bund with a water tank

maidan and platform designed to encourage social activities

The second eco area is located near the Pune junction, metro stations, and the only existing bridge in the area. At the same time, it is at the confluence of the two rivers, with more social events engaged here

Eco area three: terrace

A boat loading bay is proposed to provide space for water activities.

perspective view from the terrace

The third eco area is focused on agricultural uses because of its context. Based on the opportunity provided by the topography, we proposed a mini bay area for loading kayaks and other water activities, as well as a public playground designed for social and community activities.

Can urban growth ecologically integrate with nature ?

Pune must consider the ecological, social and financial capital of this site. We interweave the natural assets of the site with high-density development that includes mixed-use, mixed-income, and mixed heights of buildings, making the site accessible to the rich and poor alike, and strengthening Pune’s social capital.

overall strategies + road system + density plan

We suggest a new transit network by considering landscape patterns and topography. Newly added bridges will disperse the traffic and connect the site to the regional pattern. Higher density will be formed on high ground, and get less dense as it gets closer to the low ground to keep the riverfront view visible as much as possible for all locations on site.

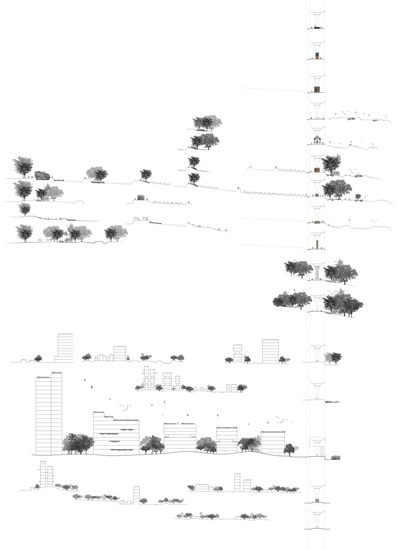

fifteen sections along the riverfront

sections showing the distance between developed area and riverfront

These sections show the amount of green space along the riverfront as well as their capability during monsoon and dry seasons.

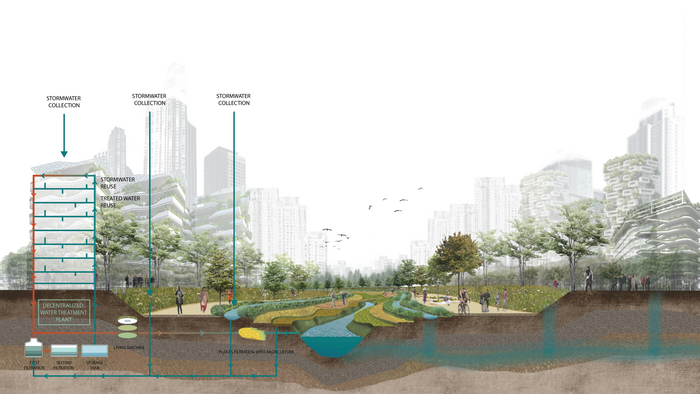

Decentralized water system

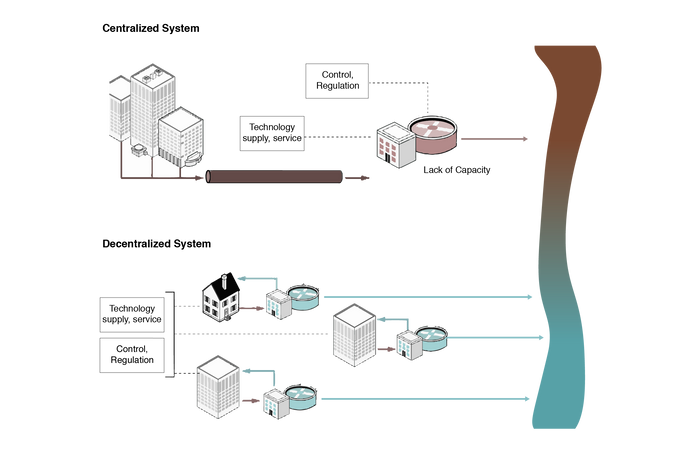

Along with dense development, we suggest a decentralized water treatment system in place of a traditional system of a single treatment plant located at a distance and connected with pipes. Each building has a water treatment system.

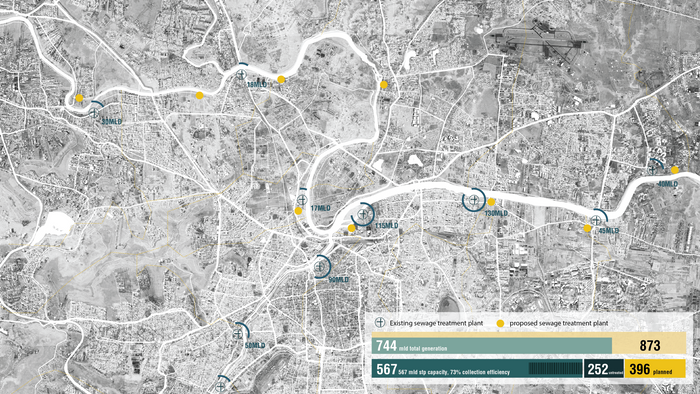

Existing sewage treatment plant

Even combining the existing and proposed sewage treatment plants, the daily demands of Pune city cannot be met.

Centralized water system vs. decentralized water system

With the decentralized water treatment system, diverse water resources are created, conserved and utilized effectively. It will also solve the water inequality issue in this area.

section of how decentralized water system works on site

The three eco-areas with landscape infrastructure will make the development more resilient. It creates a symbiotic relationship between nature and development. In rainy seasons, the eco-areas will hold the water, and decrease the risk of flooding.

We believe nature led CBD with careful consideration of transit connectivity, high-density mixed-use development, and eco area interventions can preserve the environment while still improving the quality of life and well being for all of Pune.

3

THE MIDDLEGROUND URBAN ECO-NETWORK

Students: Richard Chou, Huang Qiu, Tina Pang

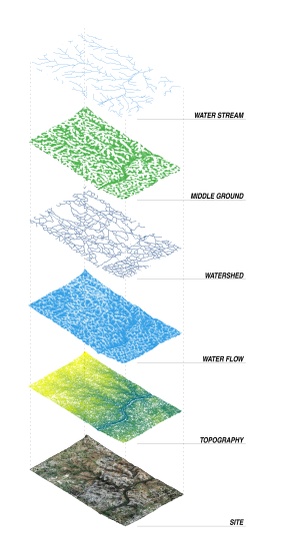

What if Pune’s expansions are grounded in the social and ecological development of the middle ground?

View of the middle-ground toward Mula-Mutha river

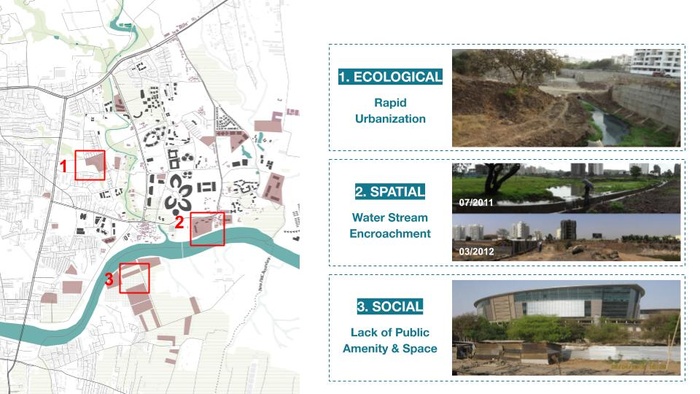

The Middle-ground Urban Ecology Network is a next-century model for balancing urban development with ecological and cultural assets in the city’s periphery. Today, Pune’s rapid urbanization of its agricultural periphery is neglecting important principles of sustainable growth, leading to increased pollution and water scarcity, while also increasing the social divide. Current degradation and the proposed concretization of the Mula-Mutha river and its streams (nallahs) are leading to the loss of typological spectrums. We propose a focus on the “middle-ground” — between built and natural landscapes to enhance the resilience of the natural, built and social fabric of the city. The Middle-ground Ecology Network is the critical buffer zone between urban development on the high ground, and water on the low ground, leveraging the seasonality of the nallah for urban agriculture and public recreation. It will become a blue-green network to provide effective storm-water management, productive wetlands as well as civic spaces that ensure the Right to the City for all Pune’s Citizens.

Project Introduction Video

Site Context

Concretised Nallah at Kharadi, Pune

Concretised Nallah at Kharadi, Pune

Concretised Nallah at Kharadi, Pune

Located in Pune’s Eastern periphery, Kharadi is the city’s fastest-growing area. Home to the booming IT industry, Kharadi has attracted large numbers of investment and new development. But today this rapid urbanization is destroying the natural buffers between development on the high ground and water streams on the low ground.

By 2015, the Kharadi Basin had lost ⅓ of its streams and wetland. Now the city’s sprawling expansion has targeted Mundhwa, the neighboring village across the river from the IT park. It is experiencing a large amount of farmland loss to make way for luxury housing developments catered to new urban dwellers and investment, representing the same kind of urbanization pattern that displaces productive farmland and local people and their livelihood all around Pune’s periphery.

Pune is growing to become India’s fourth largest Metro area but also growing into a sprawling unsustainable city

The newest peripheral urban center is unable to provide a healthy and sustainable environment for its residents

Currently diminishing wetlands in the middle ground around natural water streams (nallahs)

Systems Dynamics

The current development pattern reinforces the continuous encroachment and exploitation of local livelihoods and ecology

We propose to change the current pattern by creating water and ecology-oriented development, and design for social equity

Establishing the Middle-ground

The Middle-ground Urban Ecology Network is a next-century model for balancing urban development with ecological and cultural assets in the city’s periphery. Starting with the government supported protective zoning, the network will leverage new developments to co-develop the middle ground maintained by development policy, corporate contributions, and community stewardship.

Identifying the ‘relative’ middle ground via surface water flow

Identifying the ‘relative’ middle ground via surface water flow

A wholistic blue-green network that stems from the nallahs to the Mula-Mutha

Microscale network connecting urban green spaces as extensions of the network

Design Strategy

By being strategic with where urban density is placed, the Middle ground can become a place of collective green space and the critical buffer for urban resilience. The middle ground will be the blue-green network that provides effective storm-water management through three distinct typologies described here.

Development to convert Mundhwa as a residential hub and TOD displaces local farmland and livelihood

Proposal for Mundhwa as a TOD threatens the natural vegetation, farmland, and local farmers’ livelihood in the area

The design shows how the middle ground can provide space for public amenities and urban agriculture

A comprehensive stormwater management system can protect settlements on the high ground

Detailed Components

A comprehensive stormwater management system can protect settlements on the high ground, and replenish natural wetland and the low ground. At the same time, the middle ground can provide space for public amenities and urban agriculture, giving Pune a much needed healthy common ground that benefits the water system, ecology, and people from all walks of life ensuring the Right to the City for all Pune’s citizens.

Connections Between Different Ground Levels

Seasonal stream-bed with agriculture & water filtration

Seasonal stream-bed with agriculture & water filtration

Public amenities & water holding systems

Functional (permeable) infrastructure that direct water

A functional (permeable) infrastructure that holds and directs water

Eco-Smart City

Proposed here is a next century model that shifts from land-use based urbanism to water-based urbanism. With the urban ecology network in place, Pune can become the first “eco-smart” city of India.

The program can be designed responding to Seasonality

Pune as the First Eco-Smart City of India

Turning From High Ground Centric planning to Middle Ground Centric planning

4

Metro, Myna and the Mula-Mutha

Students: Alexandra Burkhardt, Lorena Galvao, Maria Palomares

What if Pune’s Metro could initiate ecological restoration, improve livelihood and expand habitat?

![01_1a_[Metro].jpg](https://d37vpt3xizf75m.cloudfront.net/api/file/UYGgNlBhRUSjVPOx0jjn/convert?fit=max&h=550&w=700&compress=true&fit=max)

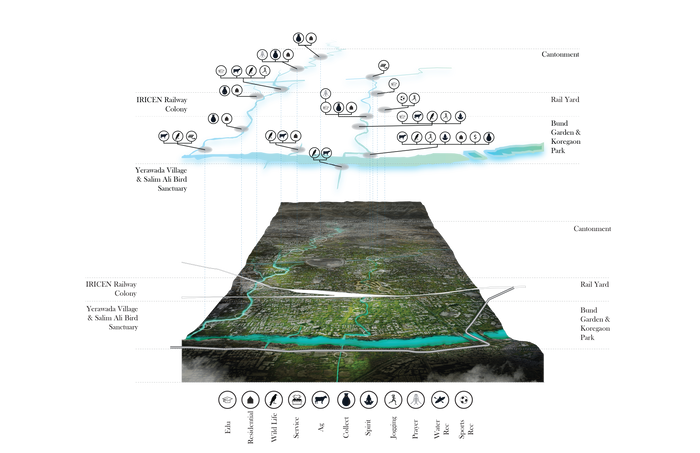

Multi-Use Armature: Our Vision for a 21st Century Pune

Might the disappearing birds of Pune be a warning sign that Pune will no longer be “the most livable city in India”. Today, the proposals for three large, divergent and mono-use development projects are imminent threats to humans, flora and fauna that will disrupt the last remaining hotspot of biodiversity in Pune, the Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary. We propose to address the current and future city-wide challenges of development, ecology and waste by reimagining the Metro, currently under construction, as a multi-use armature anchoring an integrated water and waste systems shed.

This nature-based infrastructure can initiate opportunities for transformative micro-infrastructure to trigger habitat expansion and livelihood across Pune. Addressing challenges of sanitation, sewage overflow and waste, community toilets can help seed micro-forests, holding tanks can generate productive landscapes, and filtration ponds can restore the ecology of the Mula-Mutha, allowing Pune to become a truly resilient and livable city. Through micro-infrastructural units, our project harnesses the agency of local stewards while leveraging the corporate social responsibility of Maha-Metro. Together, the field of interventions can have a large impact on shaping the Pune for the 21st-century.

Project Introduction Video

Will Pune remain the most livable city in India?

Pune is currently pursuing three new city-wide initiatives: a 27-kilometer Pune Metro extension, a Riverfront Development Plan and the construction of eleven Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) under the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA) plan. The three projects, separately conceived, lack integration and will not only exacerbate depletion of flora and fauna, but also bring a host of challenges inconsistent with the vision of a “smart, livable city.” We see the potential to reverse the current trajectory by rethinking mono-use development projects as opportunities for integrated, multipurpose infrastructures that not only address the challenges of livelihood, mobility and waste but also help with biodiversity and quality of life in Pune.

Our Observations of Pune

Projects, such as the Metro, do not consider the surrounding context. Unless designed to enhance the urban ecology of Pune, Metro-initiated developments pose a tremendous threat to the livability of Pune

Pune’s Metro Proposal by PMC

Not long ago, one of Pune’s greatest assets was its tremendous biodiversity. Our project focuses on the Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary, the last standing hotspot of biodiversity in Pune City.

![01_3_[MapMoment].jpg](https://d37vpt3xizf75m.cloudfront.net/api/file/TL1NGuogS7692EMi13HX/convert?fit=max&h=550&w=700&compress=true&fit=max)

Impending Development will Jeopardizes Pune’s Greatest Assets

Over the past few decades, the population increase has brought challenges of solid and liquid waste management. The city’s existing sewage and waste infrastructure is already at capacity. Infrastructure upgrades beyond the planned STPs must accompany the Metro project so that sewage overflow does not continue to spill into the Mula-Mutha, harming human and species’ habitats.

Current vs Proposed Projections - Reverting the Risk

The Consequences of The Metro on The Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary and Yerwada Settlement

Our site presents a duality of landscapes including Pune’s oldest informal settlement, Yerwada, to the west and the Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary to the east. The Metro and the 4-FAR intensive real estate development will isolate the Bird Sanctuary from the river and is predicted to cause the loss of 100+ species that regularly visit Pune. It will also wipe-out homes of people in Yerwada, a settlement of over 300,000 people that faces tremendous issues of sanitation.

The Tale of Two Cities - Yerwada Settlement and Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary

Species diversity is plummeting across all of India and our site is a microcosm of this issue. Our site is part of several corridors of movements that presents complex layers of actors

Our site is named after Salim Ali, an internationally renowned ornithologist, often referred to as, “The Birdman of India.” His life’s work centered around advocating for birds and this sanctuary is a place he strongly urged younger people to help preserve saying, “I suppose I’ve done my bit, it’s now up to you younger people”.Just as he recognized the importance of this site to the overall ecosystem of Pune, it is now more important than ever for younger generations to advocate for this site before it’s destroyed.

Salim Ali’s Call for Action

Current - Rethinking Current Site Conditions

Proposed - Rethinking Current Site Conditions

Instead of conceiving the 500-meter buffer as solely an increased FAR building zone, we have reimagined what Metro-initiated development should be. We propose the Metro as an armature that can initiate micro-infrastructures that trigger ecological restoration, improve livelihood and expand habitat across our site and Pune.

Current - Can the Metro initiate an improved landscape along the Mula-Mutha Riverfront?

Proposed - Can the Metro initiate an improved landscape along the Mula-Mutha Riverfront?

Metro Armature and System Shed

We question the continued implementation of mono-use infrastructures that threaten the liveability of Pune for humans, flora and fauna.

Rethinking Mono-use Infrastructure as Multi-purpose

Our design proposes improvements to the existing form of the Metro currently under construction.

Using the Metro as a framework, we propose:

An Expanded Landscape that filters water, cultivates agriculture and provides opportunities for human and species interaction at the riverfront

A Vegetated Canopy that lessens the ecological impact of the Metro, helps to reduce noise and air pollution, and expands bird habitat at multiple levels

A Sewage Line that forms the last line of sewage collection along the Metro, carrying waste from existing and new developments and treating waste through filtration ponds to prevent STP overflow

Community Programmed Metro Columns that support public spaces responsive to the surrounding urban fabric, including pedestrian and bike paths, rainwater collection and filtration for drinking water, public toilets, Wi-Fi, community centers, health clinics, job centers serving people in the informal sector, and small-business markets and eateries.

The Metro armature and the transformative micro-infrastructural units will create a field of opportunities and a landscape responsive to site-specific context.

Field of Opportunities

Through a connected, systemic approach, micro-infrastructural nodes and the Metro as the supporting, city-scale armature, seed new opportunities for Pune benefitting both humans, flora and fauna. Designs for three, transformative units working together to improve ecology, livelihood, and liveability across Salim Ali and Yerwada are presented here.

Transformative Micro-Infrastructural Units to Trigger an Integrated Landscape

Units of Micro-Infrastructures

The Metro armature will initiate a systems-shed that provides opportunities to filter and collect water. Using a cut and fill technique, by sticking, ponding, trenching and tanking the ground plane, water is filtered through different flows and the landscape connected so that the Metro can become an integral part of the systems-shed.

Holding Tanks: These will be strategically located within deforested, low grounds of the Bird Park. Bunds, constructed of natural materials, will form holding tanks that capture sewage flowing from nallahs of Yerwada and filter waste through anaerobic and aerobic digestion. The infrastructural fingers of the filtration network will expand wetland habitat and provide opportunities for urban agriculture and aquaculture. These tanks will bring back food production and jobs to the community, supporting the livelihood of people and species. Tanks are designed to be responsive to seasonality, holding water in times of dryness and releasing water to the Mula-Mutha in times of wetness.

Holding Tanks Can Generate a Productive Landscape

Filtration Ponds: A natural filtration landscape will be carved into the basalt between the Metro and riverfront in strategic locations. Wastewater will be released as needed into the filtration ponds, creating a protective buffer before the water meets the Mula-Mutha.

The basaltic riverfront provides an opportunity to engage humans and species. A series of paths will guide people across the basalt, providing spaces to sit, observe birds and enjoy a restored riverfront. A second Metro Station on site, the Salim Ali Station, is proposed to connect to an ecological education center to sensitize Punekars about the importance of ecological preservation, restoration and stewardship.

Filtration Ponds Create a Restorative Riverfront

Community Toilets: With the aim of expanding the Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary habitat into Yerwada and Pune City, the third unit, Community Toilets, will seed micro-forests throughout the settlement while addressing issues of sanitation, waste sorting and habitat expansion. Utilizing a cut and fill technique, the community can dig an opening for the structure and construct a lightweight bamboo platform with bamboo and corrugated metal structures over top. Units will be erected until sufficient compost is produced to seed the forest, after which the toilets will be deconstructed to other sites, the pits filled, and trees planted s on top to create micro forests and public spaces. While the toilet structure will move to the next location, individual families’ access to toilets will also increase using the government subsidies currently available for this use.

Community Toilets to Seed Micro-Forests

City Scalability

In time, instead of a tale of two cities, we envision an integrated systems-shed, building on the importance of multi-purpose infrastructures as a catalyst for livability. Instead of seeing intense building development proposed along the Metro, we envision allocation of FSI in layers that respond to the context and the flight patterns of birds.

Metro development should be designed to respond to the urban fabric specific to each station and utilize an ecological flora and fauna preservation driven approach to new construction. To protect and extend the bird habitat, building heights will be greatest farthest from the Metro and step down to the Metro height, to improve the flight path of birds into the bird sanctuary. New buildings will be required to incorporate green roofs and facades, intermediary floors for species habitat and ground-level wetland landscapes, increasing green surface area and integrating a thriving forest into the city.

A Bird Landing City

FAR Guidelines

Conclusion

Our project questions the implementation of mono-use infrastructures and large scale projects unresponsive to nature and the site context. We believe employing small scale transformative micro-infrastructure units can leverage knowledge from local stewards, working independently and cohesively to create large scale impact.

We see birds as an indicator of the quality of an ecosystem and also of the interconnectedness of city sites. Birds in Pune migrate from as far as Siberia and Europe, highlighting the importance of broader systems thinking to create an integrative, restorative landscape. In doing so, ecology, livelihood and habitat for a liveable, 21st century model for Pune can be addressed.

5

NALLAH-HOOD

Students: Noah Shaye, Ryan Pryandana, Shouta Kanehira

What if the waterways and built environs could become an interconnected water system that not only holds, filters and distributes water but also provides a social and cultural benefit as well?

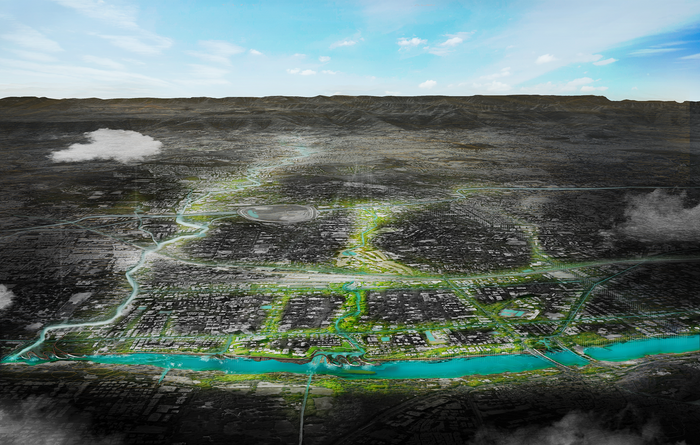

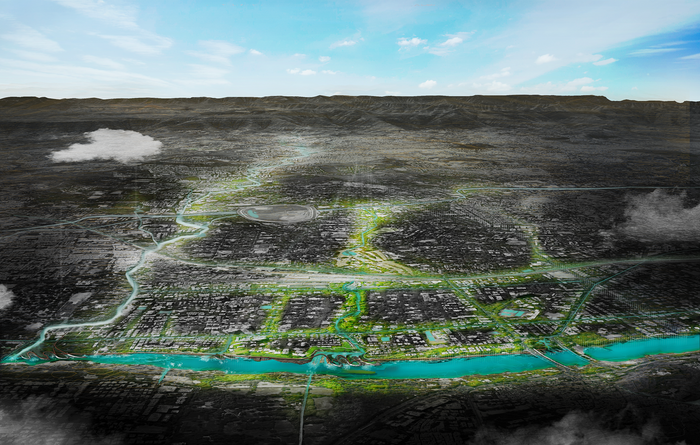

The interconnected waterways and infrastructures of the Nallah-Hood water holding network

In order for Pune, India, to harness the full potential of its watersheds it must see its waters as one unified system of a river, rain and its nallahs. Nallahs are inherently decentralized, demarcate the low ground and have great potential to hold water. Pune’s watersheds or Nallah-Hoods could significantly help to mitigate issues related to flooding, water scarcity, pollution, and habitat loss. A water holding system cannot be realized without first taking an in-depth look at the pollution issues that surround the cities waterways. Our proposal is three-pronged. The first and most important system is the water holding network of Nallahs and interconnected infrastructures. The second and third system work in parallel. One system implements a web of physical waste collection and waste harvesting points that incentivizes communities to collaborate in the waste management of their neighborhood. The other system filters and treats polluted nallah water before its eventual release into the Mula Mutha.

Project Introduction Video

Pune and The Mula Mutha River

Pune, India, sits in the midst of the Western Ghats and their natural pattern of water flows, but the city has failed to harness the potential of this pattern. Currently, an array of water infrastructures such as reservoirs, dams and barrages control the water that flows down from the Western Ghats and across the city. The Pune Municipal Corporation’s intention is to create a perennial but artificial waterfront by building an additional three barrages. This approach may serve the wealthier residents and tourists, but ignores larger issues of urban ecosystems and water scarcity in the city and should be avoided. Our proposal challenges the PMCs megaproject approach and provides a more socially and ecologically resilient alternatives to it.

Khup Varshan Purvi, Once Upon a Time

Once upon a time, the monsoons would soak the densely forested Western Ghats and the waters would flow down to low grounds of the Deccan Plateau.

The current state of Pune with its reservoirs, dams and existing barrages

he city-wide nallah network

Pune is ripe with opportunities for sustainable development, and the existing network of waterways might just be key to the cities holistic transformation. In order to fully harness the potential of the nallah network, the city must change its negative perception of the Nallah. This will not be a simple task but one that our project takes direct aim at. The city could jumpstart this process by defining itself based on the Nallahs watersheds rather than ambiguous political wards.

Findings and Analysis

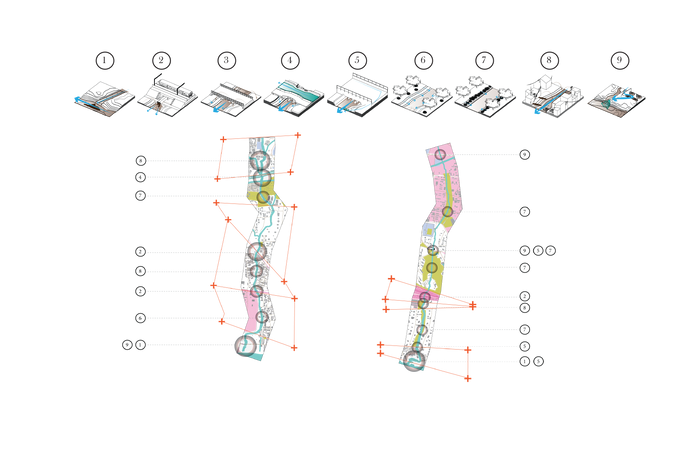

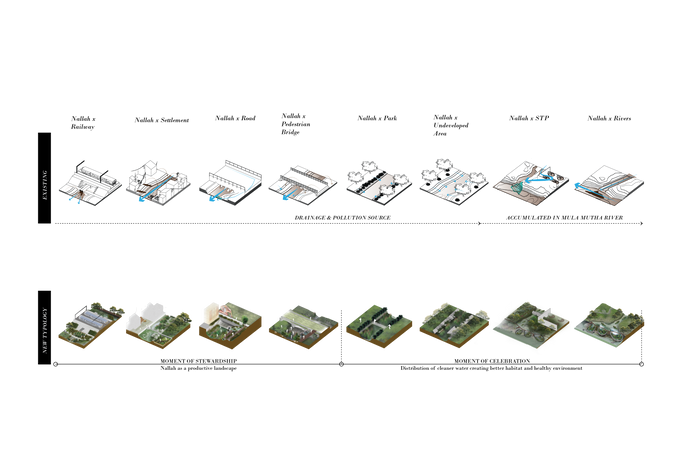

Today, Pune sees nallahs as drainage gutters for dumping and effluent release. They also face issues relating to encroaching of informal settlements, water pollution and concretization of many of the waterways. The areas we studied include the Bund Garden, the Koregaon Park neighborhood, the Iricen Railway Colony and nallah that weaves its way through this landscape.

Nallah Intersection Analysis

This diagram evaluates two nallahs, one from our site, and one from the adjacent nallah to show how the intersection of these typologies can be applied to determine the specific design moves can be made in specific locations based upon the context.

Nallah Intersections Transect Analysis

We evaluated the typical intersection typologies where the nallahs meet the urban fabric. We also see clear potential in areas where the nallah meet existing infrastructures and greenspace.

Transect Analysis: The Bund Garden, the Koregaon Park neighborhood and the Iricen Railway Colony

The logos resemble the variety of programs that exist along these corridors, some of which include residential neighborhoods, dumping sites, shopping districts, and areas for passive and active recreation.

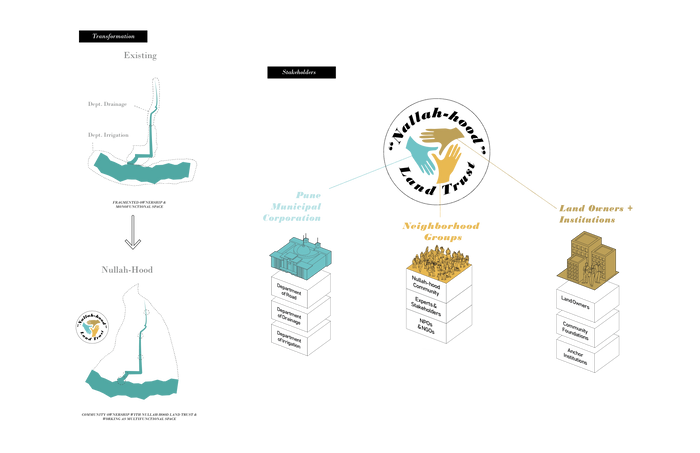

The Nallah-Hood Model

The holding system is the centerpiece of our proposal. This graphic shows the interconnected water holding network. De-channelized Nallahs, streetscapes, and other green spaces can serve as holding grounds that will feed into the low grounds and eventually into the Mula Mutha, mitigating the danger of flash floods.

Interconnected water holding network, de- channelized Nallahs, streetscapes, and other green spaces can serve as holding grounds

We propose creating a land trust of combined ownership between the PMC, neighborhood groups, local stakeholders, landowners and neighboring institutions to jointly own, maintain and benefit from the nallah.

Intersection Transformation: Each intersection provides an opportunity to begin transforming the nallah

Instead of intersections that are currently monofunctional spaces, we propose transforming each intersection into a catalytic landscape that holds and filters water, harvests waste and transforms the nallahs into a productive environment.

The Nallah-hood is defined by the Nallahs topographical watershed, social context and related infrastructures

The Plan highlights the possibilities where the nallah intersects with the Railway Colony

The intersections serve as nodes for water holding, filtering and waste collection. Our site design shows how the Nallah stitches together a network of intersections to create a landscape that empowers members of the Nallah-Hood Trust to transform their communities’ Nallah.

Applying the Nallah-Hood

Details of the nallah-hood concept will be localized depending on the issues and needs of specific neighborhoods. The representative sites we have proposed designs to show the variety of potential interventions both physical and administrative. Each intervention introduced in our scheme is intended to have multiple functionalities and impact. The resulting landscape would boost the city’s water holding capacity while creating healthier environments for people, animals, and plants.

Interventions Highlighted: Contour trenches, waste and sludge harvesting area, and Bund Bridge Filters

Interventions Highlighted: Waste Collection Points, Fishing Area, Sluice-scape for adjacent Agriculture

Easy to access activated nallah edge

De-channelized nallah with gabion filter structures

Nallah-Hood Trust Planting Campaigns and Community Nallah Engagement Opportunities

There are several unique design opportunities proposed at the Iricen Railway Colony. The transformation brought about by our design will be most evident during the Monsoon season. By de-channelizing the edges of the Nallah we can significantly increase its water holding capacity. Waste collection points and bioremediation plantings are essential elements that can begin the Nallahs transformation immediately.

Interventions Highlighted: Heavy duty, waste harvest access, connection of streetscape bioswales to nallah, and community access points

Estuary Bunds, Multifunctional Green Spaces, community access, and increased habitat for flora and fauna.

Interventions Highlighted: Community access via network of paths or boardwalk, connection between adjacent Nallah estuaries along the banks of the Mula Mutha

Interventions Highlighted: Estuary bunds designed to increase holding capacity during the monsoon season

The Nallah estuary is designed to hold and filter water with the estuary bund and terraces. During the monsoon scenario, the estuary bund will hold and slow the water from the Nallah reducing the volume of water in the Mula Mutha and minimizing flood risk. In dry season, the water will be held and utilized as habitat for flora and fauna, and human activities. The terraces will filter and hold the Nallah overflows, and at the same time create room for the River to rise. he Nallah estuary concept can be replicated across Pune.

Community Lead City Transformation

Now is the time for Pune to begin their transformation. The Pune Municipal Corporation and local stakeholders need to get organized immediately to fully realize a nallah network. The joint ownership model of the Nallah-Hood Land Trust can provide a framework for this transformation but the initiative must be driven by the people. The Nallah-Hoods purpose is to provide structure for the communities transformation.

Interconnected water holding network, de-channelized Nallahs, streetscapes, and other green spaces can serve as holding grounds

Conclusion

The city is facing a multitude of pressures and the Nallah-hood concept provides the design direction necessary to solve many of Pune’s most pressing issues like seasonal flooding, water scarcity, and pollution. If Pune wants to harness the potential of their waterways they must change their relationship with their nallahs. The Nallah-hood can empower the city to harness this potential and the result will be a healthier more resilient Pune. So Pune, Begin with the Nallah-Hood.

The city-wide nallah network

6

EX-PAUSING PUNE

Students: Carolina Godinho, Alexandros Hadjistyllis, Adi Laho

What if we enhanced cultural pauses and natural flows to restore and revalue the ecology of the Mula Mutha?

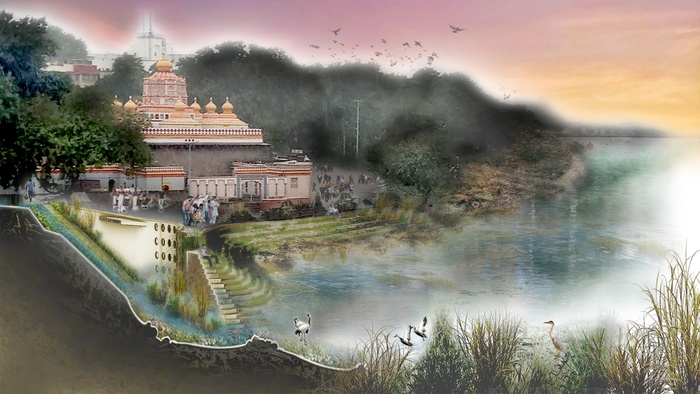

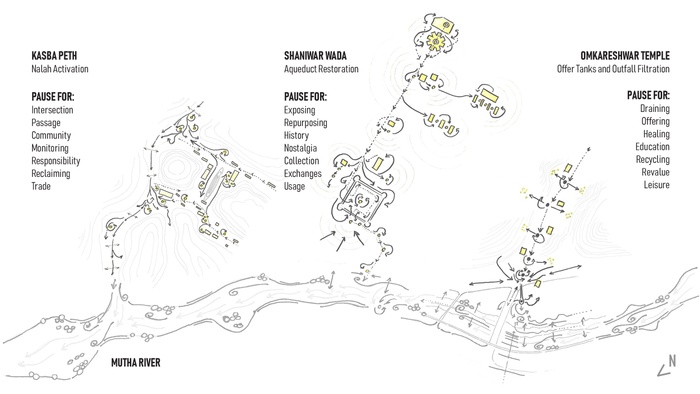

Identifying cultural points in the Old City, and linking them to the Mutha river

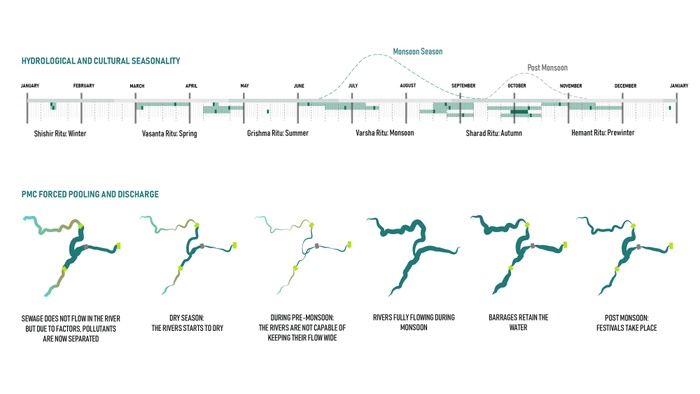

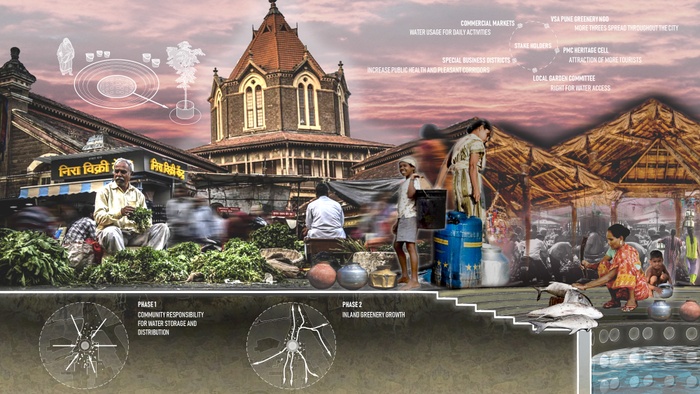

Pune is a city forced to rush at a terrible cost to ecology and the quality of life of people. The proposed developments by PMC are focused on increasing the pace of flows. Their engineered and hyper-efficient infrastructure reinforces the disconnect between the Mula Mutha and the neglected ecology of the city. As an alternative to this engineered pace, we propose to enhance and exploit cultural pauses and introduce natural flows.

In three very distinct sites of the Old City, we explore the positive and cumulative effects of water networks that connect to the Mutha River. Using the unique opportunities these sites already possess we highlight the qualitative benefits of flows and pauses of these water networks for the benefit of the Old City and the river.

Restoring the ecological character of the river: PMC versus “Ex-Pausing” proposal

Project Introduction Video

What is a pause?

A Pause is a moment in rush. It is an opportunity to breathe, create, generate, mold, or simply break from forced movements. It is an opportunity to produce an enhanced quality of life in a rapid urban fabric through interacting and embracing the benefits of water, flora, and fauna.

Expanding pause from the city down-contour; allowing water to craft spaces of hold and eddy

Linking Mutha edge design through cultural and ecological opportunities

Shaniwar Wada and the Reactivation of a Water Network

In Shaniwar Wada we reactivate an old buried aqueduct system that runs seven kilometers from the Katraj Lake to the Mutha River. We reveal this system at specific sites through stepwells that work as social spaces as well as moments of pause along Heritage Walks and ritual processions that connect religious institutions and markets. At Shaniwar Wada and at the confluence of aqueduct with the Mutha River, the opportunities afforded by these social spaces as places of pause for people participation and vegetative growth are particularly enhanced.

Partial exposure of the old aqueduct and strategic placement of connections within existing crosspoints

Partial exposure of the old aqueduct and strategic placement of connections within existing crosspoints

At Shaniwar Wada, the old aqueduct repowers the fountains of these historic gardens, aerating the water as it flows around the interior of this ‘phytoremediation pause’.

Giving purpose and function back to a site that once wholly encompassed the nature of pause

Linking back together a disconnected landscape through the transformation of the edge

Beyond the historic fortress of Shaniwar Wada, we revive a maidan that once gathered people around the aqueduct in a ‘historic pause’. Here, the water is not only cleaned before reaching the Mutha River; it becomes an integral part of Old City’s pride through a new outfall filtration strategy that builds sediment and reforms the river edge. Platforms based on sediment plateaus provide accessibility for residents and visitors to the river and metro while also serving as sites of filtration.

Stakeholders

We imagine a stakeholder network where the local community has the right and accessibility to water in their daily use. They take responsibility for this new enhanced green commercial corridor that reconnects them to a source of cleaner water and provides them with sites for community engagement.

Cleaner water & utilities begin to change the level of positive community engagement

Assembling layers of the proposed filtration tank

Suggested Guide for Ex-Pausing Citywide Implementation: Starting with the Old City as a Site Specific Pilot

1. Raise Awareness, Educate and Engage Actors

Form a stewardship based model to create a new river/land responsibility approach.

2. Value and Conserve

Historical, natural and ecological systems to define a biodiverse landscape unique to Pune.

3. Implement and Construct

Design of new and existing water networks that starts upstream; not only at the Mutha River.

4. Integrate Community though Linking Landscapes

Embracing the urban fabric at the water edge, beyond the red-line. Connect neighborhoods with informal settlements through the creation of blue-green filtration networks. Spawn more opportunities for public access and a commons for all.

5. Citywide Generation and Green Growth through the Concept of Pause and Water

6. Recycle and Repeat Throughout

Replicability of the Strategy - Nak Zari Nallah

We restore the Nak Zari Nallah as a critical water network that gathers waters from upstream and intersects with the Mutha River downstream. We see opportunities of pause along this Nallah that work to transform the polluting practices of informal settlement of the Bhavani Peth. And at Kasba Peth, we make the Nallah a new waterfront, filtered by phytoremediation before reaching the Mutha River.

Phytoremediation occurs repeatedly as a secondary and tertiary layer of filtration along the Nallah, so it prevents any pollutants from transferring from one water body to the other

The Nallah is seen as a microcosm of the former glory of the Mutha edge and sets a new paradigm for future edge conditions; in time and in space

Replicability of the Strategy - Sambhaji Park

Sambhaji park is one of the few green spaces in Pune. In this corridor, we design pauses that exploit the high concentration of schools and temples as well as waste collection and recycling, and religious processions. As a first step in implementing this plan, we propose the installation of a new drainage network that revalues “waste” and religious sites through filtration.

This network and strains out organic offerings before they clog the waterways. We use these strainers to create a field of pauses with composting tanks that spawn ecologies and revalue daily cultural practices. These pauses lie in the courtyards, schools, and offering tanks, spreading awareness of recycling waste from festivals and beyond.

The use and education of this drainage and offering network revalues the concept of waste

How design and a new multi-purpose outfall strategy can trigger a pause for connection

Conclusion

Wrapping moments of pause around the holding of water has the power to change Pune. These moments prompt and enhance green growth, public gathering, and participatory engagement while also providing accessibility and introducing possibilities for filtration.

We believe that Pune has immense potential for such moments of pause in the existing fabric of the city, a city that should not be in a rush…

7

MULA MUTHA SANGAM

Students: Shuo Yang, Keju Liu, Jinsook Lee

What if the Mula Mutha Sangam could recover its position as a sacred place through celebrating the confluence of ritual and ecology?

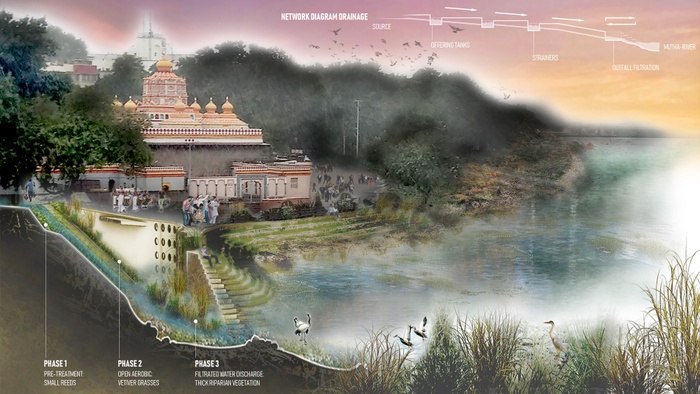

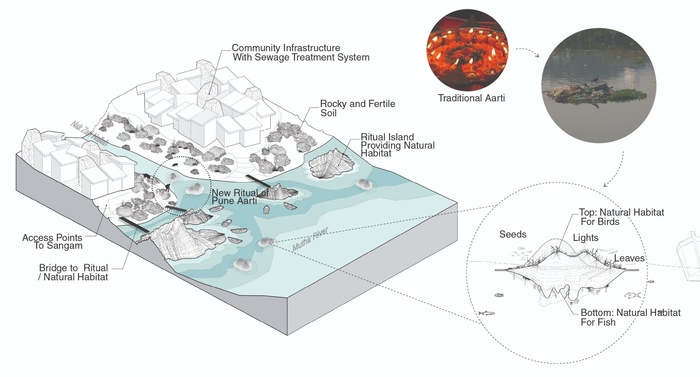

Reimagined Sangam as a confluence of ritual and ecology

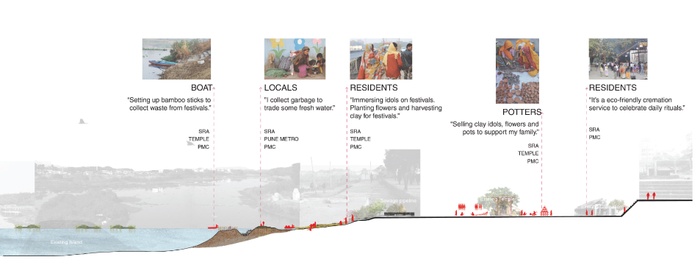

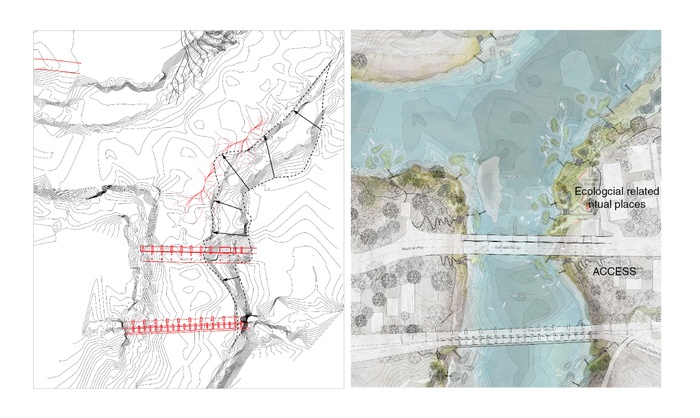

Sangam is a traditional sacred place in India where rivers meet. In Pune, it is the confluence of Mula and Mutha Rivers, located in the geographic center in Pune. However, today, this Sangam has been degraded with untreated sewage and debris from daily and festival rituals, damaging Pune’s eco-systems. We want to leverage and re-interpret rituals to heal and enhance Pune’s ecology and resilience. Since many Pune rituals were once rooted in ecology, we want to introduce new rituals for restorative eco-building by residents of Pune.

Project Introduction Video

We believe that part of the current neglect stems from the Sangam becoming increasingly inaccessible, so we propose improved access to the River, connected to public spaces and markets. This is different than the hard-edged concrete wall approach currently being considered by Pune, which will destroy Pune’s ecology and turn stakeholders into mere consumers of the Riverside public parks. We propose a multi-scaler system for this regeneration including micro-scale sewage and waste infrastructure, macro-scale ecological healing and, finally, the process of social engagement that will include schools, temples, and NGOs. We believe that it is only such cooperative effort that can bring the Sangam back to the position as a ritual and an ecological asset of Pune.

Ritual Asset & Ecology Asset

What is Sangam? Sangam is a traditional sacred place in India where rivers meet. In Pune, it is the confluence of Mula and Mutha Rivers, located in the geographic center in Pune. It is an ecological asset and a sacred place where lots of ritual and social activities happen. While many rituals were once rooted in ecology, rapid urbanization and population growth of the city have resulted in the Sangam also becoming a destination for untreated sewage and debris from daily and festival activities, damaging Pune’s eco-systems.

Geographic Location of Sangam

Ecology & Ritual Asset

The Sangam in Pune is being choked with waste and ritual debris

Lack of sanitary facilities, adequate sewage infrastructure in informal communities, and a very large increase in population making ritual offerings at temples is the cause of water pollution.

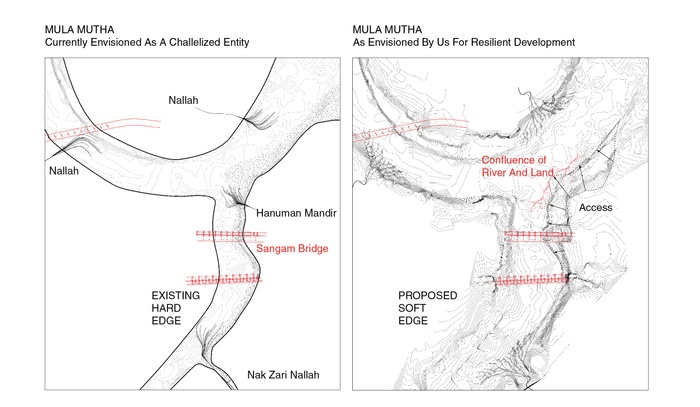

Design Language Generation

Current Mula Mutha plans envision a channelized entity restricted by concrete embankments. This will further deteriorate the relationship of people to the River, as has been the case where Nallahs have been channelized, and are now seen as places to dump waste. However, in our project, Mula Mutha is envisioned as an opportunity to advance rituals and ecological resilience by creating soft edges. Multiple access points to the water with eco-islands in the river can maximize the confluence of people, land and water. The constructed islands and wetlands will help decentralize rituals and purify water in a multi-scalar systems.

Transforming hard edges to soft edges

Rather than decreasing accessibility of people and river, multi-access of soft edges will provide opportunities to engage people and enhance the ecology

Maximizing access points using constructed eco-islands will create multi-scalar waterfront programs and purifying systems

Access points will include public spaces, markets, community gardens, and other proposed infrastructure. Islands of various scales and combinations planted with plants for phytoremediation will form the water purifying and holding systems.

Leveraging Ritual to Build Eco-Islands

In our project, the market or urban agriculture-based access points will connect people, communities, water and land. To leverage ritual and for healthier ecology, we encourage people to help build Eco-Islands with waste and phytoremediation plants rather than throwing waste and plastic idols into the River. We propose upcycling of festival debris through Eco-Island landscapes to reduce pollution and clean the River water. Meanwhile, constructed Eco-Islands will also become access points for decentralized rituals spots in the future.

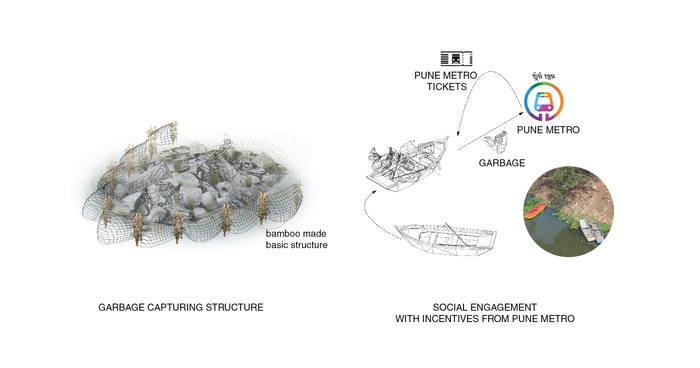

Proposed community based on garbage collection system is the first step for constructing Eco-Islands

Bamboo fences will be set up to capture waste from the water. Boats can act as movable garbage stations to collect inorganic waste and transport to the metro stations for recycling. We propose to add value to trash so people bringing sorted waste can earn social credits, and redeem them for metro tickets, freshwater or eco-friendly detergent.

Clay captured from immersed Ganesha idols will be re-used to form new idols in idol making workshops, for making Eco-Islands and also ritual ponds away from the water for dispersed idol immersion

Various islands constructed by ritual behavior will enhance the ecology of the Sangam

Bamboo fences will be set up to capture waste from the water. Boats can act as moveable garbage stations to collect inorganic waste and transport to the metro stations for recycling. We propose to add value to trash so people bringing sorted waste can earn social credits, and redeem them for metro tickets, freshwater or eco-friendly detergent.

Nallah Purifying System

Regenerating and restoring the ecology and biodiversity at nallah scale is our second goal, which can be achieved by creating a water purifying system and changing residents daily behavior. We propose identifying public land along the nallah including informal settlement area. We then propose modular units for the treatment of sewage. Once the nallahs are clean, people can perform their rituals at the nallahs also. The floating island of phytoremediation material including algae on the river are also proposed, which can provide habitats to birds and fish. Turbulence caused by these islands would help in water purification.

Current nallahs drain into the River without any water purification or garbage collection system

Proposed Waste Collecting and Sewage System

Creating a garbage collection system in nallahs and changing nallahs from hard edge to soft edge will help purify water and maximize access for social engagement and amenities like a playground, community gardens, markets, toilets, and new ritual places. When the nallah meets the river, it will then discharge purified water rather than pollute the River.

New ecological ritual in nallah

Daily ritual behavior of Aarti, the act of floating an offering lamp in a plate made of leaves can be changed to floating a small scale bioremediation offering, which can be combined to form small floating islands that will also form floating habitats for birds.

Engagement

Social engagement including residents and institutions like schools, temples and Metro Authority can cooperate to form this multiscalar waste infrastructure and improve ecological habitats to bring the Sangam back to its position as a ritual and an ecological asset of Pune.

Conclusion

Social engagement including the cooperation of residents, schools, temple, and Metro in these multi-scales sewage systems, waste infrastructure, and ecological habitats brings the Sangam back to the position as a ritual and an ecological asset of Pune.

Three moments: Seasonal wetland and ritual land, riverfront, market and temple

Afterword

Afterword

Author: Geeta Mehta.

Why Pune should heed the urgent call of this Studio?

With an open-minded bureaucracy looking for innovative solutions for improving their city, Pune would be smart to “hear” the call of this Studio and make the bold changes necessary in its current development trajectory towards becoming a truly eco-smart city. This is a call to listen to the sound of falling forests, worsening flash floods, the drying wells, and the people in informal settlements aspiring for a dignified life, and the last cry of species becoming extinct. It is a call to ensure that large infrastructure projects benefit rather than hurt the city in the long run. Because other cities in India follow Pune’s example, Pune’s leadership at this time is important.

While the projects in this document are the work of just one semester, it is the work of post-professional students from around the world. It is also Columbia University’s seventh urban design studio in India, so the faculty, many of whom have life long experience in India and other countries, are well versed in the complexities of urbanism. The passion to contribute to a resilient Pune was palpable in the Studio. While the proposals were never expected to be shovel ready, all projects point to the need for course correction that PMC should consider. They are a collective call for alternative ways of thinking about Mula Mutha and mono-use infrastructure, which are different than the intentions underlying the current plans for Mula Mutha created by Mr. Bimal Patel that PMC is considering.

Following the ten design principles articulated in this document the Studio has built upon, here are seven ideas that Pune can embrace now:

1. Think bigger than the current Mula Mutha plan

While the current proposal of concretizing/beautifying few areas along the River into amusement parks and promenades are OK, such plans should be considered only after a larger plan to clean and revive the entire Mula Mutha ecology has been prepared and launched. This holistic plan would include not just the River, but also its nallahs and other water holding spaces, bio-swales and productive landscapes along all water ways and in all low lying areas. The projects proposed in this publication have shown how this does not need to be a massively expensive mega plan, but a smart incremental plan where micro-projects will add up to a much more resilient and sustainable Pune over the next decade and beyond. However, this strategic plan is important and must be made now.

2. Think smaller

Waste is a design problem that should be solved at the source, rather than accumulated and solved with mega engineering solutions. While the current plans for Mula Mutha are being seen by PMC as a one-time project/product, river cleaning and ecological restoration is an ongoing process. As such, it is critical to engage all stakeholders, including the developers, businesses, institutions, residents and religious rituals in a systematic, transparent and accountable manner. While behavior change is difficult to bring about, once it happens, it will be powerful, making the Mula Mutha eco-system increasingly cleaner and more robust. Mechanisms such as Social Capital Credits, proposed in some of the projects in this publication, can be developed so that the communities along the waterways become responsible for maintaining and benefitting from this living infrastructure. Micro sewage treatment plants in every community would lessen the burden on the larger sewage treatment plants (STPs) currently being built with the help of JICA, since even the newer STPs are predicted to prove insufficient in the future.

3. Re-envision Pune Metro as a socio-economic Lifeline

The Metro in Pune, as also in other Indian Cities, can be re-imagined as a socio-economic development corridor for all, including the people in informal settlements and the rural-urban migrants, who are predicted to increase in number for at least the next two decades. This migration is desirable from the national development point of view, since people make more money, have fewer children, and improve their health and skills once they move to cities. The Metro Lifeline could become a beacon of hope and support for the people at the all levels of the social and economic pyramid, with welcome centers giving them information about jobs, housing, health insurance, and education for their children. The Lifeline could include Internet cafes, toilets and bathrooms, banks, community centers, libraries, markets and night shelters that offer affordable safe sleeping spaces on temporary basis. Since Metro columns are numbered, migrants could register with a welcome centers located at specific columns, which could become their temporary address for availing of social services till they find homes that they can afford. The amenities and social spaces in this spine could also become places where the rich and poor rub shoulders with each other, contributing to the unity in community”. The traditional methods of environmental custodianship practiced in India were deeply holistic, and are being seen as critical innovations in cities like New York. It is clear that no government in the world, no matter how wealthy, can care for the environment and face increasing climate risks on its own, so public participation is an important part of any progressive resilience plan today.

4. Social equity is critical for a Smart City

A smart city must be designed to empower all, including the poor, and the women. Harnessing the social capital that every human being brings to the city is important for realizing India’s demographic dividend within its short window of time remaining. All new property developments should be mandated to include affordable housing. Gated communities that interrupt the urban fabric and result in social segregation eventually lead to loss of safety and social capital in cities. This has proved to be the root of problems in Brazil, Colombia and indeed in the newer parts of Indian cities like Delhi. Residential or commercial communities, which are serviced by the poor but do not provide housing and amenities for them, should not be permitted. Street-based urbanism adds to the safety in a city, while car centric gated communities of towers hurt the poor as well as the rich. Mixed use and mixed income areas that are walkable bring vitality to the city, while shortening the travel time for residents. Public transport, public spaces and pedestrian paths must be gender sensitive with good lighting, visibility and access.

5. The expanding periphery

Pune needs tight controls on urban sprawl. Peripheral development, where allowed after careful review, should be of high density, which is easier to serve with infrastructure and reduces travel times, while protecting the farmlands and forested areas. Increasing property values in urbanizing areas do not make agriculture and forests unaffordable. The “highest and best use” of land argument holds only if the value considered in the financial value alone, at the expense of ecological and social values. PMC has the responsibility to consider future-facing “values” for Pune, and to safeguard these values with legislations. To protect long term welfare of the people and broader values is indeed the main responsibility of any government. Preservation of the nallahs and ponds on the low grounds, and preserving the middle-ground as the place for ground water recharge, flood risk mitigation, agriculture and natural assets should be part of every development plan.

6. Triple Bottom Line accounting for corporations

Pune can lead the way in harnessing for urban development the Indian legislation that requires large companies to commit 2% of their revenues for Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Accountable and transparent systems such as Social Capital Credits can be designed so that CSR funds go towards improving the nature based infrastructure, hard infrastructure, inclusive public spaces, and protection of the farmland and forests. Pune can also lead the way in legally requiring that companies above a certain size include in their annual reporting the triple bottom lines of financial capital, social capital, and ecological capital. Along with Environment Impact Statements required of every new property development project, Social Impact Statements should also be required. This will enhance rather than hurt Pune’s popularity as the destination for high tech industries, since the employees at such companies are demanding a higher quality of life and environment than the more polluted and ill planned cities in India can offer.

7. Urban policies are only as good as their implementation

Regulatory frameworks to enable and execute holistic solutions will be the key to Pune’s resilient future. Good urban policies will have no impact unless their implementation is strengthened. Making stakeholders, corporations, institutions, NGOs, and Resident Welfare Associations (RWAs) responsible for specific activities and areas that are transparent and accountable can enhance such implementation. The current public discourse on urban issues, mostly centered around the NGOs in Pune should not be discouraged, but expanded to include education institutions, businesses and citizen groups, with specific responsibilities.

Some innovations proposed in this document may sound not “modern” or “photo op” enough. However, they are more far reaching and necessary for the long-term resilience of Pune than the last century mega projects currently on the table. We hope that they will be carefully considered.

End

Acknowledgments

Columbia University Faculty:

Kate Orff (studio coordinator), Dilip da Cunha, Geeta Mehta, Thaddeus Pawlowski, Julia Watson, Linh K. Pham

Columbia University Students:

Donghanyu An, Zilu He, Pei-Jou Shih / Yanli Zhao, Yinzhe Zhang & Huiwon Hong / Richard Chou, Huang Qiu , Tina Pang/ Alexandra Burkhardt, Lorena Galvao, Maria Palomares / Noah Shaye, Ryan Pryandana, Shouta Kanehira / Carolina Godinho, Alexandros Hadjistyllis Adi Laho / Shuo Yang, Keju Liu Jinsook Lee

Academic Partners:

College of Engineering Pune (Dr. Arati Petkar & students)

BVIEER: Institute of Environment Education and Research, Bharati Vidyapeeth University, Pune (Dr. Shamita Kumar & students)

Partners and Collaborators:

100 Resilient Cities, Mahesh Harhare (Chief Resilience Officer (CRO), Michael Berkowitz, Samuel Carter, Gemma Kyle, Saurabh Gaidhani, Michelle Mueller; Columbia Center for Resilient Cities and Landscapes Linda Schilling , Research Scholar

Pune Municipal Corporation: Mr. Mangesh Digeh & team

Published By:

Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation Urban Design Program 411 Avery Hall, 1172 Amsterdam Avenue New York, NY 10027 United States of America

![01_1a_[Metro].jpg](https://d37vpt3xizf75m.cloudfront.net/api/file/k31gCUfnTe2QmS8q4PP3/convert?fit=max&h=550&w=700&compress=true&fit=max)

![01_1b_[River].jpg](https://d37vpt3xizf75m.cloudfront.net/api/file/UtpXvUR6RRu2n0jR3VDh/convert?fit=max&h=550&w=700&compress=true&fit=max)

![01_1c_[Waste].jpg](https://d37vpt3xizf75m.cloudfront.net/api/file/qwG4aTTLT9HlXppiiGCQ/convert?fit=max&h=550&w=700&compress=true&fit=max)