1

Extended Stay: i.e. “The More Things Change, the More Things Stay the Same”

Behind the Houston Processing Center, there is a motel, a prison farm, a plantation, a Supreme Court case, a tax exemption, a landlord, and a developer. To echo Stephen Dillon in this book, it could go “on and on and on and on and on and on and on.” (269–291)

About $25 a night can get you a single room, a bathroom down the hall, and three meals in a Houston hostelry, which seems pretty reasonable at today’s prices. In fact, it isn’t even the “guests” who pay. But there’s a drawback. They can’t check out at will… —Marjorie Anders, describing the Houston Processing Center in Clovis News Journal, August 4, 19851 1

In November 1983, the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) received its first federal contract from the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) to build an immigrant detention center in Houston, Texas. The following April, it opened the Houston Processing Center, designed to accommodate roughly 350 individuals. It took just five months for the CCA to finance, design, build, and open the Houston center—though still not fast enough for the INS, which had already begun to enforce the more punitive policies of the early Reagan administration and to carry out a mode of governance that conflated criminal and immigration procedures.2 These policies had spatial consequences, taking shape in new architectural devices meant to support a broader and enduring carceral system that instrumen- talizes and weaponizes the built environment.

On January 22, 1984, with the construction for the Houston Processing Center underway, the CCA opened an interim facility at the Olympic Motel along Interstate 45. The motel’s short-lived role as detainer is preserved only in a horrifyingly hokey video of CCA cofounders T. Don Hutto and Tom Beasley recounting the early days of their company.3 The INS had “very unrealistic expectations,” says Hutto. “They gave us ninety days.” The two arrived in Houston on New Year’s Eve to begin searching for their surrogate detention site: “We were both getting pretty weary. We had found a lot of places, but nothing seemed quite to work, nothing you could secure in a short period of time. Then we saw this big ‘ole sign: the ‘Olympic Motel.’”4 They made an offer to lease the place.

Once rented, the CCA installed a 12-foot cyclone fence around the perimeter of the motel, “laced with bamboo to thwart the curious” and topped with coiled barbed wire.5 The pool was drained and filled in with sand. The rooms were secured, windows outfitted with iron bars, and doors with exterior locks. Promising to return the motel in “three times as good a condition” and to leave all the “improve- ments in place,” not much else was done to the existing building. Signs were left untouched: “Olympic Motel,” “Color TV, Radio, Telephone,” and “Day Rates Available” were still advertised to the highway. The renovation was an exercise in DIY securitization that included Hutto, American Express card in hand, running to a Houston hardware store for supplies and a Walmart for toiletries; the CCA hiring the landlord’s family as staff; and the motel employing additional guards from ABM Security Services. On Super Bowl Sunday of 1984, Hutto produced ad-hoc photo ID cards and fingerprinted individuals himself while other company leaders “distributed sandwiches and helped security staff escort detainees to their living quar- ters.”6 The architectural sleights of hand carried out at the Olympic Motel modeled the ease with which motel slipped into detention site, living quarters into cells, and hostelry into (site of ) captivity.

This slippage is at the heart of the CCA’s founding. Describing the company’s premise, co-founder Tom Beasley once said you could “sell prisons ‘just like you were selling cars, real estate, or hamburgers.’”7 Or, considering that CCA obtained its initial funding from serial entrepreneur Jack Massey—famed eventual owner of Kentucky Fried Chicken and founder of the Hospital Corporation of America (HCA)—it was just like selling fried chicken or hospitals. The forced equivalence underwriting CCA’s corporate model prefigured its speculative and opportunis- tic development model, which registered the built environ- ment through spatial analogs.

An intertitle from the CCA video of co-founders T. Don Hutto and Tom Beasley discussing how they secured the first of many contracts for housing detained undocumented immigrants. Courtesy of The Nation and posted to YouTube, February 27, 2013, link.

That the Olympic Motel came to house 140 asylum seekers and undocumented immigrants awaiting deportation over the course of four months ultimately faded into obscurity once the official Houston Processing Center opened. Hutto and Beasley’s use of the motel is now a self-professed scrappy origin of one of today’s largest for-profit prison corporations—CCA “was a start-up before start-ups were fashionable. We met the dead- line, the detainees arrived, and a new relationship was forged between government and the private sector.”8 This privately run detention facility speaks to a particular spatial tendency within the larger neoliberal project: “enterprise zones” that privatize the usual functions of the state. The company found an untapped site of possibility in the space behind bars, a space cleared by the social engineering, deregulation, and financialization of the 1970s and 80s, which converted government, corporations, and citizens into opportunities for investment and capitalization.9

The CCA positioned itself as the answer to two interrelated problems: corrections bureaucracies—“the most entrenched bureaucracies of all”—and the growing demand for detention space.10 The company sold a more “efficient” and “economical” delivery system of detention from construction to operation. Its ability to open the Houston Processing Center in roughly five months and at a cost of $14,000 per bed—opposed to the two years and $26,000 per bed it would have taken the INS—was celebrated by proponents of privatization.11 Today, the company claims that it delivers cost savings up to 25 percent and cuts the construction time of new facilities by 40 percent. Unencumbered by red-tape (like public approval), the company could “act faster than public agencies in everything from [attaining funding to choosing a site] to construction to buying shampoo.”12

In 1967, Jack Massey, then owner of KFC, wrote a letter to persuade family friend Tommy Frist Jr., who was struggling to decide whether to pursue a career in business or medicine, to join the company: “Chicken, beef, or medicine. Make your decision soon.” The note inspired Frist Jr. to choose a hybrid of the three. In 1968, Massey and Frist Jr. founded HCA, a “new kind of hospital company.” Courtesy of HCA.

The Olympic Motel modeled the private-prison product CCA would ultimately become known for. It gave built form to the fiscal conservatism and tough-on-crime policies of the time that also recast asylum seekers and refugees, primarily from Latin America, as criminals. On the heels of the Mariel boatlift and in the midst of a raging civil war in El Salvador, the INS saw detaining large numbers of asylum seekers and refugees as a form of deterrence. By 1982 “all aliens without proper travel documents [were to be] detained pending a determination of their status.”13 Not only did the INS’s budget for detention grow exponentially throughout the 80s (from $15.7 million to over $149 million) but so did its capacity to hold individuals and the average length of detention (from approximately 7 days in 1984 to 23 days in 1990).14 As the INS intensified its policing and detaining efforts in the border region, US senator Lloyd Bentsen aired that it seemed the entirety of South Texas had become a “massive detention camp.”15

In the context of this hostile territory and to the desperate eye of the CCA, the Olympic Motel offered 12,466 square feet of latent detention space. While this particular narrative of corporate annexation fell in line with a longer history of recycling and reusing sites of internment, it also marked the beginnings of an increasingly pervasive model that propagates the need it intends to fulfill. It is a model in which architecture is both the promise and the guarantor of carceral expansion. The fast and cheap delivery of beds at the Olympic Motel satisfied the current demand and also incentivized a future demand. It was proof for the CCA that they had not only devised an iterable scheme for the privatized service of carceral detention, which presupposed its continuance on a new market, but also that they had innovated a system of delivery through the built environment.

Between Use and Misuse

Olympic Motel at 5714 Werner Street, along the North Freeway, Houston, TX 77079, pictured here with a billboard advertisement from Texas Christian University that reads “Opportunity is Waiting.” © Google Street View 2015.

The case of the Olympic Motel shows how the late-capitalist carceral system might be less about producing new architectural forms than constructing new uses out of an otherwise familiar spatial environment. It is a story that recounts both the situated origins of a particular model of carceral production and the pervasive workings of neoliberalism. Sara Ahmed writes that “use offers a way of tell- ing stories about things,” that “what has been used in the past can just as easily point us toward the future,” and that “if use records where we have been, use can also direct us along certain paths.”16 That the Olympic Motel was taken up, put to use, or misused by the CCA on behalf of the INS is not intended to overly “direct” attention to the prominence of private corporations in the prison-industrial complex, nor is it intended to perpetuate the misconception that private prisons are the “corrupt heart” of this system of incarceration.17 Rather, it is a story of urban-carceral transformation that evidences how the state—in this case through its corporate appendages—moves, restructures, and expands itself across the built environment accord- ing to its coercive functions. This is a narrative, then, that traces the sites of production, buildings, legal proceedings, rhetorical arguments, and financial instruments it uses to do so. The path that emerges from the Olympic Motel offers a way to describe contemporary carcerality, which entangles the devouring tendencies of privatization and the sanctioned punitive policies of the racial state. In other words, the short-lived fate of the Olympic Motel helps to tell the story of the status quo. “What is the status quo?” asks and answers Ruth Wilson Gilmore: “Put simply, capitalism requires inequality and racism enshrines it.”18

Use is contingent on the form it is given by practice, ideology, and policy. That the Olympic Motel could be “secured in a short period of time” speaks not only to its architectural characteristics but also to longstanding and widespread social beliefs about what kinds of places contain, support, enable, or are needed by certain ways of life. Take, for instance, Justice Antonin Scalia’s dissent in the 2015 Supreme Court case City of Los Angeles v. Patel:

Motels not only provide housing to vulnerable transient populations, they are also a particularly attractive site for criminal activity ranging from drug dealing and prostitution to human trafficking… Motels provide an obvious haven for those who trade inhumanmisery.19

This vision of how crime and poverty are distributed in space directs how the motel is legislated, policed, and circumscribed along racial lines—“insofar as geography,” as Jackie Wang observes in Carceral Capitalism, “is a proxy for race.”20 Scalia’s statement evinces the biases that enlist the motel as a mechanism of racial enclosure. The degree to which crime is inherent at motels, and thus the degree to which those who use, live, or reside in them are criminalized, deprived, and immobilized, is also determined through a partisan push and pull. In the majority opinion, Justice Sonia Sotomayor articulates her own argument about the intended and non-intended function of architectural objects: “Hotels—like practically all commercial premises or services—can be put to use for nefarious ends. But unlike the industries that the court has found to be closely regulated, hotels are not intrinsically dangerous.”21 While this juxtaposition may in some ways reproduce an all-too-easy dichotomy between conservative and liberal agendas, it also demonstrates the way in which judicial and political arguments proscribe and prescribe legitimate uses of state force in the built environment. At the very least, these contrary opinions insert the motel and the manifold vulnerabilities, itinerancies, and possibilities that it supports into the struggle over how and where carceral state power is expanded and justified.

“We can ask about objects by following them about,” Ahmed writes.22 This call to attend to the “strange temporalities of use” unsettles certain assumptions about the built environment’s relationship to and participation in the carceral state. It offers a way to unfix the prison as a place and also as a set of political, pedagogical, and theoreti- cal concerns. This implies eschewing the often all-too-sta- ble concept of “site” and “place” within the discipline of architecture. It is a specifically architectural misprision to understand incarceration as a solid architecture that one is “put into” or “let out of,” an isolated and neatly pack- aged typological envelope of discipline and control. Paths to Prison: On the Architectures of Carcerality is instead premised on an understanding of the prison as a diffuse, porous, and mobile entity that coordinates the tactics, materials, and bodies that circulate beyond and through it. It is concerned with the “both/and” of the prison, where “the physical instantiation of the carceral is at once everywhere and also very specifically somewhere,” as Wendy L. Wright writes. (363–384) That is, this book attempts to register the mobility of carcerality—which casts the prison as a machinery of oppression, a social and political economy of confinement that extends well beyond the institution’s walls.

The prison pervades, with various degrees of intensity and duration, the everyday terrain between distinct spaces of containment: typologies and histories and lived experiences assumed to be “outside” of the sphere of incarceration. As Brett Story offers, “to consider ‘ordinary space’ is therefore to contend with how the prison system etches its violence into the social fabric in ways as diverse and complex as they are quiet and mundane.” (211–237) To bring this idea back to the history of the Olympic Motel, it is perhaps the motel’s ordinariness that obscures the extraordinary circumstances that have come to mark and mobilize it.

To understand the prison today, one must pursue, as Jarrett M. Drake powerfully proposes, “not a cultural biography of things but rather an ethnography of exchange.” (241–265) This book aims to trace the contours of such an exchange. It follows the objects and ideologies that under- write the prison, how they ebb and flow across the carceral continuum in the present, tracking how these objects and ideologies mutate in their historical course. The Olympic Motel models a very discrete exchange—a single site that moves “through hands, contexts, and uses” with enormous consequences for the lives within it—while also demand- ing that we look elsewhere, in time and in place, to see how such spatial fungibility is made possible. To tell the story of the state’s insatiable custodial appetite, one must pursue various protagonists (human and otherwise), slip between past and present, and move across both discursive and material sites. It requires a narrative that is not set spatially or historically but that, in its movement, pieces together a layered geography of carcerality. Drawing on the struggle, imagination, and potential of Black women’s geographies to reframe and undo traditional geographic “arrangements,” Katherine McKittrick writes in Demonic Grounds “that our engagement with place, and with three-dimensionality, can inspire a different spatial story, one that is unresolved but also caught up in the flexible, sometimes disturbing, demands of geography, which some people ‘wouldn’t think was so sane.’”23 Paths to Prison is deeply indebted to McKittrick’s work and seeks to engage the long tradition of thinking, living, and writing oppositional discourses that resist and find ways out of dominant spatial patterns that actively try to block the possibility of holding various places, practices, and oppressions in mutual relation.

Accounting for architecture’s participation in the carceral state means leaning into inconclusiveness. This book thus also emerges from an invitation put forth by Avery Gordon in Ghostly Matters to “make contact with what is without doubt often painful, difficult, and unsettling” and to write new stories about “what happens when we admit the ghost—that special instance of the merging of the visible and the invisible, the dead and the living, the past and the present—into the making of worldly relations and into the making of our accounts of the world.”24 Gordon’s ghost—like McKittrick’s unresolved story and Ahmed’s proposal to follow—offers new epistemologies, methodologies, and ways of writing for the field of architecture. It insists that current accounts of the built world carry the full presence or weight of the past and insists on registering how the supposedly “over-and-done-with” is materialized in “new” forms and “new” structures. Paths to Prison proposes that we look behind and across carceral sites to see how historical forms of racial violence and dispossession are inherited, learned, determined, naturalized, and struggled over in the present—how incarceration manifests or reenacts racial, economic, and social hierarchies.

As Dylan Rodríguez poignantly states, the term “mass incarceration” has “canonized a relatively coherent narrative structure, based on a generalized assumption that such juridically sanctioned, culturally normalized state violence is a betrayal of American values as well as a violation of the mystified egalitarian ethos that constitutes US national formation.” (97–128) Taking Rodríguez’s diagnosis as a challenge, this book aims to counter the apparent stability of that narrative with non-linear and mobile accounts of the seemingly disparate institutions, ideologies, practices, and spaces that enforce and perpetuate carceral power. It picks up the argument that this work is constitutive of and faithful to the foundations and values of the United States of America—that what we have come to call “mass incarceration” is not an aberration among American values but representative of them.

When I get out of Cummins I’m goin’ up to Little Rock. I’m gonna walk right up those Capitol steps, And I ain’t gonna even knock. And if the legislature’s in session, There’s some things I’m gonna say. And I’m gonna say, gentleman… You say you’re tryin’ to rehabilitate us, Then show us you are… —Johnny Cash, “When I Get Out of Cummins,” performed at Cummins Prison Farm, April 1969.

On April 17, 1969, prisoners of the Cummins Prison Farm at the Arkansas State Penitentiary filed a suit in the District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas to chal- lenge the conditions of their confinement. They argued in Holt v. Sarver that the prison’s isolation unit constituted “cruel and unusual punishment” in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments.25 Two months later, Judge Jesse Smith Henley agreed with the prisoners, conclud- ing that their prolonged confinement in the unit was not only “mentally and emotionally traumatic” but “physi- cally uncomfortable,” “hazardous to health,” and “degrad- ing and debasing.”26 Judge Henley ordered injunctive relief and required Arkansas’s Commissioner of Corrections— Robert Sarver, the named defendant in the case—to report the progress being made at Cummins.27 This case sparked an almost decade-long series of litigations against the Arkansas Department of Corrections (ADC), which culmi- nated in the 1978 United States Supreme Court case Hutto v. Finney. The petitioner in this final litigation was Terrell Don Hutto, the head of the ADC between 1971 and 1976— and the future cofounder of CCA.

On February 18, 1970, prisoners of Cummins and the adjacent Tucker Intermediate Reformatory filed additional claims against the ADC in Holt v. Sarver II—citing that the entire system, not just the specific practice of isola- tion, amounted to “cruel and unusual punishment.” Judge Henley ruled again, this time more vociferously, against the entire state penal system: “For the ordinary convict a sentence to the Arkansas Penitentiary today amounts to a banishment from civilized society to a dark and evil world completely alien to the free world, a world that is administered by criminals under unwritten rules and customs completely foreign to free world culture.”28

To the petitioners of Holt v. Sarver II, Cummins ex- tended a familiar political-economic system of power, violence, and exploitation, with “rules and customs” rooted in the nation’s history of slavery. Unfreedom at Cummins was anything but “alien” to them, as Judge Henley would have it. The prison farm reeked of the plantation. Their claims expressed a lived historical consciousness, not a departure from some body of civilized norms. Cummins enshrined a set of practices and forced labor that was not “foreign to free world culture” but integral to it. Despite his denunciation of the system, Judge Henley rejected the petitioners’ additional assertion that forced, uncompen- sated prisoner labor violates the Thirteenth Amendment, which states that “neither slavery nor involuntary servi- tude” shall exist “except as a punishment for crime.”

While much has been written about how the Thir- teenth Amendment rearticulated a model of labor exploita- tion based on racial subjugation—forced upon those made unfree by criminalization rather than by bondage—the legal arguments in Holt v. Sarver II are evidence of another transition. The case documents not only how the state of Arkansas exchanged the plantation for the prison farm in the twentieth century (swapping one form of incarcera- tion for another) but also how legal rhetoric and language obscures this particular typological fungibility in the pres- ent. The question of how slavery endures is a question of how it metamorphosed in its abolition; it is a question that offers a framework to excavate the legal, economic, and social regimes that shape—with various degrees of consis- tency/inconsistency, continuity/discontinuity—the spaces and practices of captivity rationalized by “crime” and those rationalized by “race.” In other words, in what ways does Holt v. Sarver II continue (or not continue) the work of the criminal justice system post-Emancipation more broadly, which, as Angela Y. Davis has said before,“played a significant role in constructing the new social status of former slaves as human beings, whose citizenship status was acknowledged precisely in order to be denied”?29

Cummins Prison Farm, today called Cummins Unit, is a 16,600-acre maximum security prison and working farm that houses up to 1,876 individuals. It is the oldest prison in Arkansas alongside the Tucker Unit. In 1897, as the state took an outsized role in determining labor rela- tions with the land following Reconstruction, the Arkansas General Assembly authorized public “purchase with funds at its disposal [of] any lands, buildings, machinery, live- stock, and tools necessary for the use, preservation, and operation of the penitentiary.”30 A few years later in 1902, the state purchased the Cummins and Maple Grove plan- tations from Edmond Urquhart, one of the “oldest cotton oil men in the country,” for $140,000.31 In 1916—three years after the state abolished convict leasing and turned more fully to penal farms—it gobbled up the nearby Tucker plantation in Jefferson County too. That Cummins Prison used to be Cummins Plantation—and that Arkansas’s prison system consolidated the acreage of a planter class— was not unique. There was “Ramsay” in Texas, “Angola” in Louisiana. These names signaled the exchangeability, inextricability, and slippage between sites of labor: one under (and governed by) slavery, and one apparently not.

Descriptions of prison life at Cummins and of the economic system circumscribing it reproduce this metonymic link.32 Judge Henley’s 1970 opinion quoted extensively from a report prepared by the Penitentiary Study Commission of 1967 on the fertility of Cummins’s land and the profits reaped by the state from the prison- ers’ labor. 33 According to the report, there were 9,070 acres of land in cultivation at Cummins; the principal crops were cotton, soybeans, vegetables, and fruit; and prisoners tended to 2,070 cattle, 800 hogs, 40 horses, 160 mules, and 1,600 poultry. In 1966, the prison made $1,415,419.43 from the sale of crops alone. Rational and capitalistic, Cummins was representative of the “ideal goal for southern penology” in the early twentieth century.34 While the self-sup- porting prison farm was dressed in reformist and agrarian rhetoric—not only claiming to “make a man out of Ishmael” or “good” laboring citizens out of criminals but also requiring the warden to “be an experienced farmer of known executive ability”—it maintained a brutal economic form underneath.*

Men assigned to the fields are required to work long hours six days a week, except for a few holidays, if weather permits. They are worked regardless of heat… The men are not supplied by the State with particularly warm clothing for winter work, nor are they furnished any bad weather gear. There is evidence that at times men have been sent to the fields without shoes or with inadequate shoes. The field work is arduous and is particularly onerous in the case of men who have had no previous experi- ence in chopping and picking cotton or in harvesting vegetables, fruits, and berries. What skills they may acquire in connection with their field work are of very little, if any, value to them when they return to the free world.35

The court’s verdict that the carceral machine in Arkansas was not slavery, the prison farm not the plantation, is indicative of the way formal law eclipses lived experience.36 The analogic reasoning of Holt v. Sarver II reifies social and spatial boundaries. These legal distinctions follow strictly semantic definitions that prohibit the judicial system from coming to terms with embodied realities on the ground, which reproduce similar systems of production marked by a racial-colonial-capitalist matrix of exploitation, accumulation, and dispossession. At the same time, from a contemporary perspective, it is crucial to take stock of all the ways that prison labor today is different from slave labor; all the ways that logics of exploitability co-exist with logics of disposability in carceral labor relations; all the ways that the mechanisms of dehumanization, which shape the laboring body under these regimes, emphasize different devalued identities and subjectivities.37 However, the legal emphasis on how the prison farm and the plantation are categorically not the same—especially when, in the case of Cummins, it is the same land, the same soil, being tilled over and over again—forecloses the possibility of seeing how they might be interlocked, or at least tethered to one another, in a shifting and drifting narrative of institutional evolution that exists in unfinished and inexorable ways, across space and time.

To determine whether the ADC as a whole constituted “cruel and unusual punishment” required evaluating it against other prevailing (and constitutional) systems, practices, and conditions. It required extending analogical models across time and across status quos. Judge Henley’s opinion was inextricably linked to what is, or what was at the time, considered “modern.”38 His interpretation of “cruel and unusual punishment” was contingent upon this modernness too: “The term cannot be defined with specificity. It is flexible and tends to broaden as society tends to pay more regard to human decency and dignity and becomes, or likes to think that it becomes, more humane.”39 In addition to declare what the institution was not—“We are not dealing with free world housing; we are not deal- ing with theatres, restaurants, or hotels”—the court had to establish a comparative model to assess how “bad” or how different the ADC was from other acceptable, or more palatable, correctional administrations elsewhere. These statements about typology contain implicit judgements about who deserves certain protections and who does not, which in turn determine the quality of life of those subject to the law: again, “we’re not dealing with children… but with criminals.”40

Cummins Prison Farm, 1973. Photograph by Bruce Jackson.

Cummins Prison Farm, 1974. Photograph by Bruce Jackson.

Cummins Prison Farm, 1975. Photograph by Bruce Jackson.

Cummins Prison Farm, 1975. Photograph by Bruce Jackson.

Cummins Prison Farm, 1975. Photograph by Bruce Jackson.

Prompted by Henley’s ruling, what change would come over the next decade would be piecemeal and superficial. In 1971, Sarver would be replaced by CCA’s T. Don Hutto, who was then warden of the W.F. Ramsey Unit, a notoriously brutal prison farm in southeastern Texas. As the new commissioner of the ADC, Hutto would, among other things, attempt to modernize and streamline certain conditions at Cummins, building new facilities to alleviate overcrowding and converting the manual farming opera- tion to a more mechanized one.41 In 1973, Judge Henley would release the ADC from the court’s jurisdiction, writ- ing, “the Court is convinced that today it is dealing not so much with an unconstitutional prison system as with a poorly administered one.”42 This ruling-cum-warning would continue to play out in the court. In 1976, Judge Henley would rule again that specific aspects of the ADC were indeed unconstitutional, citing, in particular, two of Hutto’s innovations: the punitive wing of the new East Building and the “grue” disciplinary diet (which he had brought and introduced to Cummins from Ramsay).43

Writing in the New York Times on February 17, 1978, only four days before the case would be argued in the United States Supreme Court as Hutto v. Finney, Thomas O. Murton—the superintendent of Arkansas’s penal system before Robert Sarver—summed up the “Arkansas effect:” “The hearings have come and gone, four commissioners of correction have come and gone, paid staff guards have replaced the former inmate guards, new buildings have been erected. But the more things change, the more they apparently remain the same.”44

On June 23, 1978, delivering the majority decision for the Supreme Court, Justice John Paul Stevens affirmed that certain conditions of confinement in Arkansas’s pris- ons were unconstitutional. While the legal question had been diluted to whether punitive isolation for more than thirty days violated the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments (the answer was an equivocal yes), the case also revisited the routine abuses suffered by incarcerated people in Arkansas. That the question of forced labor at Cummins was only a footnote in this final decision— and that the Thirteenth Amendment was absent—is not surprising. Rather it speaks to the ways that contesting an entire social institution, “from the fields to the hole,” on the basis that it reenacts the brutalities (and racial control) of another is continually thwarted by the court. The law serves to entrench social and racial hierarchies: it only offers remedies when claims against those hierarchies are non-intersectional and non-systemic. The persistence of the plantation model short-circuits questions of constitutionality. It should not be minimized: the long legal arc of Holt v. Sarver marked the first successful lawsuit filed by incarcerated people against a correctional institution—and no matter how incremental the change was, it represented, in the words of Judge Henley a decade earlier, the first large-scale “attack on the System itself.”45 Yet to rule against the cumulative damages, harms, and effects of the penal system would mean to admit or rule against forms of violence that are foundational to US jurisprudence—and to acknowledge that normalizing systems of power tread through and across supposedly “over and done with” historical antecedents into the present.

Between Freedom and Unfreedom

Paths to Prison: On the Architectures of Carcerality invites the discipline of architecture to think about typology diachronically—to extend the geography of architectural inquiry to encompass “plantation futures,” which, as Katherine McKittrick writes, offer a “conceptualization of time-space that tracks the plantation toward the prison and the impoverished and destroyed city.”46 Rather than recapitu- late the neoslavery narrative, this book asks: How is the logic of the plantation reconfigured in post-slave contexts, and how might these logics undergird or pass through socio-spatial life, organization, development, and expro- priation in the present?

The warning, however cliché, from Thomas O. Murton about the supposed reforms of the Arkansas Department of Corrections—“the more things change, the more they apparently remain the same”—resonates with legal scholar Reva Siegal’s description of a mode of “pres- ervation through transformation.” Siegal’s term offers a framework for understanding the way basic forms of racial, class, and gender domination remain intact even when the legal rules and rhetoric governing those hierarchies change as the status quo, and what can be socially stomached, changes.47 It also offers a way to evaluate to what degree white supremacy relies on the typological continuity of repressive mechanisms. This book thus asks: Which discursive formations and physical sites preserve white supremacy and maintain the blueprints for today’s racial carceral state while claiming they don’t? What other supposedly distinct typologies are entangled in this exchange?

Siegal’s proposal to hold continuity and change together can also be reframed: Notions of “freedom” are always shadowed by the ways we are made unfree by design. Jasmine Syedullah asks, “What if the spaces where we have been taught to feel most at home are hold- ing us captive?” (459–484). She argues that all imagina- tions of freedom should be rooted in the practice of inhab- iting spaces of confinement.48 Beyond the loophole of the Thirteenth Amendment, this book aims to puncture languages of liberation and bring together architectural narratives that practice this kind of inhabitation—that in addition to looking at the ways architecture imprisons, looks at the ways it apparently does not. What other loopholes—legal, spatial, financial, or otherwise—blur the distinction between freedom and unfreedom? This is another method of shifting the frame away from the prison as such and towards the promises and spaces of liberalism, as a way to see all other conditions of civil existence knotted into and connected to the prison. In this way, this book aims to describe the “double bind of freedom,” which, as Saidiya Hartman has written, intertwines the “emancipated and subordinated, self-possessed and indebted, equal and inferior, liberated and encumbered, sovereign and dominated, citizen and subject.”*

Maintaining this “bind” takes routine ideological, rhetorical, economic, legal work—which determines and distributes forms of citizenship unevenly across the built environment and renders those inequities as “normal.” The work of carceral normalization is not always overt; it is not simply carried out by extreme acts of authority or blatant criminalization but by what Naomi Murakawa and Katherine Beckett have called the “shadow” carceral state, which “operates in opaque, entangling ways, ensnaring an ever-larger share of the population through civil injunctions, legal financial obligations, and violations of administrative law.”49 It operates through “liminal,” “fuzzy,” “fungible,” and “serpentine” mechanisms that reproduce and “mimic” punishment under terms that declare themselves “not-punishment.” This book hopes to surface how the carceral state annexes that which is supposedly free from its grips and to make visible the effort exerted by this entity’s many tentacles to normalize the production and maintenance of penal power.

Where processes of racialization arise, the shadow of property generally looms. —Adrienne Brown and Valerie Smith50

Thirty-five years after its first detention facility opened in Houston, Corrections Corporation of America, now called CoreCivic, owns and operates forty-three correc- tional and detention facilities and manages an additional seven federally owned facilities—which altogether span 14.5 million square feet and hold 73,000 beds across the United States. The company has also expanded its portfo- lio to include twenty-nine residential reentry facilities and an additional twenty-eight properties that it leases to third parties or government agencies. The company’s rebrand- ing and its expanding real estate portfolio are two sides of the same coin: the corporation’s “new view of corrections” that increasingly relies on the acquisition and transforma- tion of the built environment. Not only does the company pride itself on controlling approximately 59 percent of all privately owned prison beds in the United States, but it also believes itself to be, more generally, “the largest private owner of real estate used by US government agencies.”51 The cover of CCA’s 2009 annual letter to shareholders encapsulates this relation. Titled Partnership Prisons: The Best of Both Worlds, the document juxtaposes two equally generic images: a white corrections officer and an exterior view of an unspecified facility somewhere in the desert. Save for the blurry perimeter fence in the background, the property looks like any other office park. The “best of both worlds” refers to CCA’s public-private partnerships: “the essential oversight and accountability of government” coupled with “the flexibility, efficiency, and cost effective- ness of private business.” No matter how trite, this image captures a corporation in transition—a corporation that, for political expediency, future viability, and risk transfer- ence, has managed to move seamlessly from detainer to landlord and back.

This movement is possible because of a particular financial mechanism: the Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT). Created by Congress in 1960, REITs were designed to give investors the opportunity to pool capital for income-producing real estate—entirely free from federal corporate taxes. Operating like a mutual fund, the trust structure offers stockholders the chance to invest in large- scale commercial real estate assets and earn a share of the profit without having to actually buy, manage, or finance property themselves. For a company to qualify for REIT designation, it has to derive at least 75 percent of its gross income from real estate (rents from real property) and 95 percent from “passive” financial instruments (as opposed to “active” business activities).52 This distinction between “passive” and “active” investment is crucial to understand- ing what passes the REIT income test—and what kind of bureaucratic maneuvering was undertaken by the CCA. REITs are restricted by the types of activities and services they can provide to their real estate assets, but the passage of the REIT Modernization Act in 2001 produced a loop- hole that allows companies to reap the benefits of massive tax breaks by breaking apart their active business activ- ities (the operational side of, for example, private prison management) from their passive real estate investment (such as the ownership of correctional and detention facili- ties) through subsidiaries.53

Partnership Prisons: The Best of Both Worlds. Cover of CCA’s 2009 annual letter to shareholders, link

And that’s exactly what CCA did. In 2013, the com- pany (still CCA at the time) successfully converted its corporate structure to an REIT.54 This meant that it had convinced the IRS of two things: first, that its facilities are not “lodging” or “healthcare,” and second, that the money it receives from government tenants is “rents from real property.’”55 Declaring what the company (and thus what corrections) was not (neither site of care or hous- ing) allowed CCA to claim that their property was held for investment, not operation. There is a similar denial in its second request: to consider money paid by federal agencies to incarcerate and house people as rent meant fundamen- tally bypassing the actual tenants of CCA’s facilities. The IRS’s determination opened up a redefinition of carceral space—labeling the state as the tenant and not the indi- viduals sanctioned there.

The REIT regime incentivizes building and leasing, not managing or operating. While the Houston Processing Center was the CCA’s first model of privatization (financed, owned, and operated by CCA), the company has since shifted toward other models: privately financed and owned but publicly operated; privately financed and owned but eventually transferred to the public sector (i.e. rent-to- own); and publicly owned but privately financed, designed, constructed, and maintained.56

In CCA’s 2012 annual letter to shareholders announc- ing its new tax status, the company put forth a mark- edly different image of the company: as $3.6 billion in fixed assets. Alongside the narrative of REIT-generated double-digit growth, the company doubled down on its commitment to real estate with sterile and glossy aerial photographs of its properties—described not according to function but to acreage, square footage, number of beds, and age. These specifications were part of a new language aimed at repackaging CCA’s facilities as attractive investment opportunities.57 The company’s ability to build share- holder value was thus intimately connected to its ability to build a stable real estate portfolio. CCA’s portfolio was sold as a “just-in-time inventory” of leasable space— one that was integral to the growth model of the company. The inventory was intended to accommodate the immedi- ate and future needs of government partners and policy makers, thereby linking what the company offers (and what the company is) to whatever political, economic, and cultural climate it faces.

CCA’s tactical sprawl picked up speed between 2013 and 2016. In response to dips in national prison popula- tions and increasing criminal sentencing reforms, CCA letters to shareholders began to cite “America’s recidivism crisis,” emphasizing “alternatives” to incarceration and an increased interest in reentry programming. In three years, it acquired three “community” corrections companies. These acquisitions enabled CCA to be a “better” service pro- vider to its government “tenants,” but they also enabled the company to consolidate its increasingly dispersed (and diverse) footprint. The groundwork was laid for an emerging “treatment industrial complex.”58 If this was “the link between prison and the community,” then CCA, according to Hininger, was poised to supplant that connection as it continued to “develop a robust pipeline of acquisition opportunities in this fragmented market.”59

In October 2016, CCA became CoreCivic. With a solid REIT backbone and the foundation already laid for a pipe- line to the community, the company underwent another round of rhetorical sanitization, corporate renovation, and targeted acquisition.60 Everything about the way CoreCivic presents itself today is designed to be benign. Alongside the tagline “Better the public good,” the company adopted a “bolder, sleeker and more modern” typeface and a color palette intended to invoke “safety, strength, passion, stability, integrity and seriousness.” Its new logo? A 13-stripe American flag extruded to symbolize a building. Business offerings like “Inmate Services” and “Security” were replaced with “Safety,” “Community,” and “Properties”—new umbrella terms for an expanding inventory of diverse carceral products. Today, CoreCivic Community encompasses a vast network of residential reentry centers and non-residential services. In 2018, the company acquired Rocky Mountain Offender Management Systems (RMOMS) and Recovery Monitoring Solutions, adding to its portfolio new programs like probation supervision, electronic monitoring and GPS tracking, remote elec- tronic alcohol monitoring, random urine screening, and cognitive behavioral therapy. Perhaps not unlike the early prison-farm experiments in agricultural techniques, CoreCivic’s “community” and those in it have become the test site (and subjects) for a technological-social apparatus of governance—the gears of which have already been and will continue to be loosened for general use.

The first page of CCA’s 2012 annual letter to shareholders, titled A New View of Corrections, link The CCA also showcased Jenkins Correctional Center, Millen, GA: 105 acres, 233,000 square feet, 1,124 beds, one year old; Nevada Southern Detention Center, Pahrump, NV: 120 acres, 189,000 square feet, 1,074 beds, three years old; and Saguaro Correctional Facility, Elroy, Arizona: 34 acres, 352,000 square feet, 1,896 beds, six years old (this last facility is, in fact, the unnamed facility on the cover of the 2009 report).

The company has continued to metastasize with CoreCivic Properties. In the last few years, it has moved further into “non-corrections” space—acquiring and constructing a 261,000-square-foot Capital Commerce Center in Tallahassee, Florida, that is leased mostly to the Florida Department of Business and Professional Regulation; a 541,000-square-foot office building in Baltimore, Maryland, that is under a 20-year lease with the Social Security Administration; and a 217,000-square-foot built-to-suit building in Dayton, Ohio, for the National Archives and Records Administration, which includes 1.2 million cubic feet of storage space (90 percent of which is dedicated to the archives of the IRS).61 CoreCivic now declares itself a “diversified government solutions company”—detainer, landlord, and developer. Still, according to their 2018 SEC filing, CoreCivic Safety made up 87 percent of the compa- ny’s total net operating income—compared to only 4.8 percent from CoreCivic Community—and of that, ICE accounted for 25 percent of the company’s total revenue.62 The company may now be painted True Navy, Smoked Crimson, and Soft Gray, but, as the adage says, uttered this time by Tony Grande, Executive Vice President and Chief Development Officer of CoreCivic, “the more things change, the more they stay the same.’”63

Between Continuity and Discontinuity

The REIT regime is a regime of ownership, and regimes of ownership are racially constructed. CoreCivic’s sprawl manifests the long legacy of state-sanctioned white posses- sion—its external reach both a product and productive of settler colonial dynamics. The company’s ambition is infra- structural. Its “robust pipeline of acquisition opportunities” serves to lay claim to an even greater territory that spans corrections and non-corrections spaces, the prison and the community, already-cornered markets and new markets. In January 2020, CoreCivic announced that it had acquired an additional twenty-eight properties, which it would lease exclusively to the General Services Administration. Distributed throughout the mid-South, this additional 445,000 square feet is intended to house numerous federal agencies, including the Social Security Administration, the Department of Homeland Security, and the Office of Hearings Operations.* By catering itself to federal and state bureaucracies through property relations, the company aims to become even more “critical” to the function- ing of government—perhaps even a “critical infrastructure,” to use the federal government’s own parlance. And it is through this criticality, through its role as landlord to the state’s “non-coercive” business, that CoreCivic manages to reinscribe the punishing and criminalizing functions of the carceral state anew. For as a discursive and legal categorization, “critical infrastructure” assigns national value and security to supply chains of capital—supply chains that “make daily life possible”—and criminalizes efforts to disrupt and upend those chains.* As a technique of settler colonial governance—of invasion, expropriation, accumulation, and dispossession—these projects, writes Anne Spice, anticipate “the circulation of certain materials, the proliferation of certain worlds, the reproduction of certain subjects” and disavow the rights and jurisdictions of other subjects, worlds, and materials. (307–358) What values, beliefs, and ways of living are foreclosed or peripheral or antagonistic or dangerous to the state’s epistemology of critical infrastructure?

Paths to Prison: On the Architectures of Carcerality parses the ideological backbone of American society in order to reveal how it criminalizes any subjectivity that opts out or does not fit within the consolidating “we” of the nation— but also how this backbone is entirely dependent on and supported by the continued exploitation of these communities. As outgrowths of the state, these “invasive infrastructures” might make daily life possible, but they only do so for some, and the futures they aim to structure are settler futures.64 Perhaps the Olympic Motel was early evidence of this colonial futurity—for “colonialism is justified as using what is unused,” reminds Ahmed.65 Paths to Prison attempts to account for these Janus-faced constructions. As James Graham warns, the “double rhetoric of plight and opportunity is the cleared and leveled site on which a long string of government-backed dispossessions—of native lands, of mineral rights, of labor power, of unfree bodies—takes place.” (159–206)

This book interrogates how the groundwork is laid for this more invasive understanding of carceral infra- structure—one that folds the punishing regime (and thus the prison) into “other” regimes (ownership, knowledge, martial, and so on). It helps to elucidate that “savage encroachments of power take place through notions of reform, consent, and protection,” or through Property, Community, and Safety.66 The aim here is to complicate the metaphor of “pipelines” to prison, which so dispropor- tionately affect communities of color and which are most acutely guided by the conditions of daily life.67 While the book aims to describe various spaces, institutions, and practices that enact or reflect the structural violence of the prison, it does not intend to create hard-and-fast linkages between those sites, nor does it intend to suggest that these connections, as modes of conveyance, are smooth, easy, and without friction. The book engages “pipelines” only insofar as they can be disrupted—not a relentless or unchanging explanation for the way things are but an intersectional account that helps widen the frame used to understand architecture’s relationship to the carceral state.

If pipelines aim to guarantee a certain future and fate, then this book is assembled against these projections: “Permanence is not the goal here,” writes Adrienne Brown. (133–155) Pipelines clog and leak; they can be rerouted, subverted, blocked by official and unofficial means. Instead of confirming straight lines or tracks, Paths to Prison eluci- dates the physical and social contraptions that attempt to circumscribe or enclose certain lives, places, and communities, and the insurgent “social relations” that emerge “in excess of” (again, Brown) and against these invasive incursions.

What is it about blackness and Latinidad that turns one’s house (roof, protection, and aspiration) and shelter into a death trap? —Paula Chakravartty and Denise Ferreira da Silva68

The Olympic Motel may no longer be in use, but it is still valuable as a model and a caution for the way the racial logics of occupation, terror, and exception are injected into the built environment. “Racial difference,” writes Mabel O. Wilson, “became productive of the material conditions of modern life, fueling the unequal distribution of the resources—food and shelter—that sustain it.” (389–409) Perhaps the Olympic Motel testifies to a moment of redis- tribution, in which resources have been usurped, trans- formed, and reapportioned to serve a carceral machinery that relies on racial difference being maintained. As Naomi Murakawa reminds us, policy “produces social effects that reinforce their own stability.”69 The word “spatial” could be added to that sentence: Policy, immigration or criminal, produces social and spatial effects that promise and guar- antee the continuation of this expansion. Amidst the now sprawling landscape of immigrant detention, the motel has resurfaced over and over again.70 It is a site that not only captures the militarization against and dehumanization of asylum seekers, refugees, and undocumented people but also evidences this violence. In 2018 the Trump Administration sought to end the twenty-two-year-old Flores Settlement Agreement. Settled in 1997, Flores was the result of a class action lawsuit filed on behalf of two young girls, Alma Yanira Cruz and Jenny Lisette Flores, who had come to the US fleeing the civil war in El Salvador in the 1980s and who were instead met with the punitive and procedural brutality of the INS. The agreement set protections and standards for the treatment of minors in detention. As the world confronted the brutal conditions at immigration facilities along the US southern border in 2019, Flores emerged again in the mainstream media—revealing that at the origin of Flores, there too was a motel.

For weeks after entering the US, Cruz and Flores were locked in over-crowded rooms at a makeshift deten- tion center in Pasadena, CA. “The facility was a 1950s-style hotel shaped like a U,” recounts Carlos Holquin, the law- yer who eventually brought the case to court. “The INS essentially put a chain-link fence in front of it with a sally port and concertina wire on top.” Behavioral Systems Southwest, who had been contracted by the INS to operate the facility, drained the swimming pool. The children had no access to visitation, no recreation, no education: “The kids would essentially just hang around by the drained pool or on the balconies for days—or weeks or months— until it was determined what to do with them.”71

As Sara Ahmed writes, “We learn a lot about form when a change in function does not require a change in form.”72 In both Flores and the Olympic Motel, the perim- eter fence, the concertina wire, the iron bars, and the drained pool all signal that the motel has ceased to be a motel as we know it. They are provisional signs of a change in function, which does not compromise the existing form but communicates that guests “cannot check out at will.” Or, that, perhaps, guests are not “guests” at all. That this exchange is possible testifies to certain ideas that have coalesced around the motel already. In these stories, it is possible to glimpse how the motel is reinforced and consol- idated at the level of enclosure and also rendered typo- logically and spatially expansive at the level of an urban system of circulation and capture.

“Motel 6 Immigration Detention Camp,” 2017. © Lalo Alcaraz (M.Arch Berkeley ’91). Distributed by Andrews Mcmeel Syndication. All rights reserved.

This duality is depicted in a cartoon by Lalo Alcaraz of a “Motel 6 Immigration Detention Camp.” In it, a sign that reads “Immigration Detention Camp” has been affixed to the company’s recognizable “6” sign, and the motel’s otherwise generic little buildings surrounded by a perim- eter fence with barbed wire. The sketch makes visible the character of carcerality in the US, which is as much about mobility as immobility. The irony of this image, though, is that a motel doesn’t even need a fence around it in order to carry out the custodial practices of the state. The cartoon, which went viral alongside the hashtag #BoycottMotel6, was drawn in response to the allegations against Motel 6 for its role in collaborating with ICE to arrest guests. According to the suit:

Since at least 2015, Motel 6 has had a policy or practice of providing to ICE agents, upon their request, the list of guests staying at Motel 6 the day of the agents’ visit… Lists included some or all of the following information for each guest: room number, name, names of additional guests, guest identification number, date of birth, driver’s license number, and license plate number… The ICE agent would review the guest list and identify individuals of interest to ICE. Motel 6 staff observed ICE identify guests of interest to ICE, including by circling guests with Latino-sounding names.73

Over two and a half years, 80,000 names were disclosed and countless individuals arrested, detained, and deported as a result of warrantless searches, often in the form of “knock and talks.” These enforcement tactics repre- sent a particular regime of policing that asserts state force in everyday life through the cooperation and consent of the private sector. Motel 6 shared its guest data by choice—a choice made possible by the previously cited City of Los Angeles v. Patel, which declared that hotel/motel operators are not obligated to turn their guest data over to police without a warrant—turning the supposedly protected “bed space” of the motel room into the captive bed space of another. This cooperation finagles apparent if illusory thresholds between the right to be secure in one’s room (not to mention one’s body, home, and life) and the inter- ests of the state (which has a monopoly on violence). Given that Motel 6 owns and operates 12,000 motels and 105,000 rooms across the US and Canada, its disperse geography of “places of public resort, accommodation, assemblage, or amusement” expresses the pervasive tyranny of possible coercion or probable cooperation: “for every wall that provides shelter is one that confines.”74

This potentiality, the fine line between two radically different embodied conditions, and the degree to which the motel is used by the state as a force of immobility rely on a set of assumptions and biases that are constructed along racial, political, and class lines. Take for instance ICE spokesperson Yasmeen Pitts O’Keefe’s defense of the agency’s specific targeting at motels: “Hotels and motels have frequently been exploited by criminal organizations engaged in highly dangerous illegal enterprises, includ- ing human trafficking and human smuggling.”75 O’Keefe’s statement does a lot of work: it defines the motel as a place of deviancy, it criminalizes individuals who frequent it, and it ultimately legitimizes the agency’s strategic, racially motivated violence and excessive surveillance at Motel 6 locations across the south- and northwest. All of these fabricated conditions naturalize a continuum of punishment and a distributed form of governance organized around a building typology, enforced and carried out by cooperating institutions, organizations, and corporations. As Angela Y. Davis has famously argued, the “institution of the prison and its discursive deployment produce the kind of prisoners that in turn justify the expansion of prisons.”76 The motel is thus a spatial opportunity for ICE, as it was for T. Don Hutto.

The motel has always accommodated mobility. It, too, must be considered unstable as a site that moves between these determined oppositions. It offers a way of attending to carcerality in the built environment that is both local and general, fixed and fluid, concerned with citizen- ship and noncitizenship, freedom and unfreedom, legality and illegality, who deserves the state’s incursion and who does not. It is a site where rights are never just asserted but contested. What is a death trap for some is a lifeline to others, and endlessly vice versa. While the motel has been a useful agent of social death for CoreCivic and its corporate peers, for ICE, and for the Supreme Court, it has also been a space for asserting collective life. Other motels across the southwest are being repurposed as migrant shelters—as way stations on longer paths toward asylum.77 But even across Motel 6s, individuals are demonstrating how “it is always possible to create space for opposition within the hold of structural violence and domination, to move closer to freedom while still within the borders of hostile territory,” as Syedullah writes again. And this opposition is crucially not always expressed in loud acts of resistance but through the quiet persistence of seeking out ways to survive, to access resources not otherwise available, and to live fully. Individuals detained at Motel 6 reported being there for many reasons: some relied on the chain to escape sweltering heat, to access an air-conditioner, to find space away from their families to wrap Christmas presents.78 These examples are not intended to reproduce a hierarchy of “innocent” need or behavior. For need—“nefarious’’ (to use Sotomayor’s phrase) or not—should never be crim- inalized. Full stop. These examples instead point to all the ways one finds sanctuary, shelter, and freedom not necessarily via routes leading somewhere else supposedly free or totally different but via practices that carve out new space for mobility within even the most restricted environments and circumstances.

Between Mobility and Immobility

How the institution of the prison has been and continues to be represented is a political project. Just as the prison is discursively called on to legitimize its own expansion, it is also visually deployed to make a reality without it seem impossible. It is worth repeating Gina Dent’s often-cited statement on the grip that images of prison hold on our imagination: “The history of visuality linked to the prison is also a main reinforcement of the institution of the prison as a naturalized part of our social landscape.”79 The task of this book then is to make the familiar unfamiliar, to uncongeal the congealed, to denaturalize all that has been naturalized for us—shifting the epistemological frame away from the prison as such (or, in certain moments, zooming so far into the center of it) that we lose sight of it altogether, and recording what comes into view in its stead. Paths to Prison picks up and echoes a provocation from Brett Story: “Prisons are spaces of disappearance.”80 She means this in many ways: Prisons disappear bodies; they disappear the social crises they are tasked to solve; they are built in increasingly distant sites meant to disappear the violence, pain, and grief that they inflict and leave behind. But when directed at the field of architecture—a field that prides itself on its capacity to envision worlds totally different than our own—this proposition demands we rethink what it even means to visualize, to see or to not see, a space that actively holds itself out of view. The discursive underwrites the visual. The intelligibility of our language structures the coherence of our images. Sable Elyse Smith repeats that “scale and infrastructure are sometimes weapons. And language is both.” (293) By changing or by disappear- ing and decreasing the opacity of the vocabularies, narratives, myths, and pedagogies that confirm the prison at the center of our field of vision—and that block out all of the other architectures that prop up the social functions of the prison as it courses through daily life—perhaps the discipline can start to un-circumscribe how it imagines, understands, and rejects its own complicity in the carceral state.

The “paths” of Paths to Prison offer not a fixed or inexorable account of how things are but a set of starting points and methodologies for re-seeing the architecture of carceral society and for undoing it altogether. As paths, they let us sidestep, arrive, bypass, and look back at the prison differ- ently—carrying us through other sites, past and present, that serve “to establish a spatial distinction between the dispossessed and the free, the expendable and the nonex- pendable, the abnormal and the normal, and to manifest the ongoing production of racial boundaries of this transi- tional space,” as Leslie Lodwick writes. (413–454) By locat- ing architecture along other disciplinary paths too, we can better see its impact and be more critical about how it participates and exerts (or refuses to exert) this power. Paths to Prison intends to write new paths to prison into histories of architecture—histories that, by extending both what constitutes the carceral and what is ensnared in it, reveal more possibilities for rejecting it altogether. This is a book then that moves to see the prison anew, that shifts the frame in order to yield a different picture:

Not of concrete walls but of highways, archives, the control unit, FamilySearch, Sensorvault, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, the plantation, White Reconstruction, the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad Com- pany, fire camps, Appalachian coal mines, the Los Angeles Police Department, clinical psychology, critical infrastruc- ture, a north Harlem apartment, the Thirteenth Amend- ment, alternative charter schools, private telecommunica- tion networks, chain-link fences…

Not of crime but of oppression, redlining, debt, counter-insurgency, domestic warfare, wage theft, anti-Blackness, residential apartheid, extraction, White Geol- ogy, pathology, racial difference, surveillance, racial- colonial state violence, data colonialism, unemployment, home-ownership, imperialism, gentrification, invasion, home contracts, Otherness, stigma…

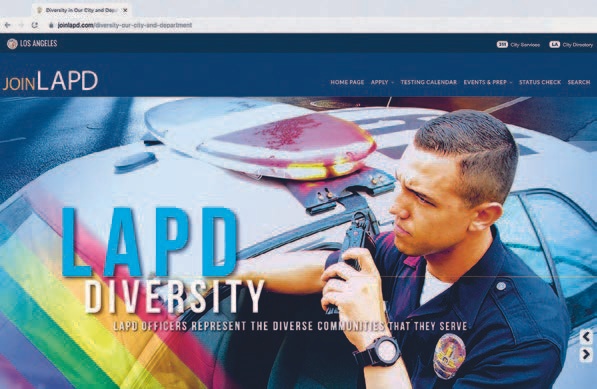

Not of only the racial state but also of liberal multi- culturalism, the American Dream, popular consent, coop- eration, diversity, reform, “something akin to freedom,” the post-racial state…

Not of social death but of rent parties, eviction resis- tance, human and other-than-human relations, homeful- ness, poverty scholarship, captive maternals, liberation, repair, rebellious affects, anti- and ante-ownership, lines of flight, sitting with what is, writing, touching, dancing, kinship, care, self-determination, waywardness…

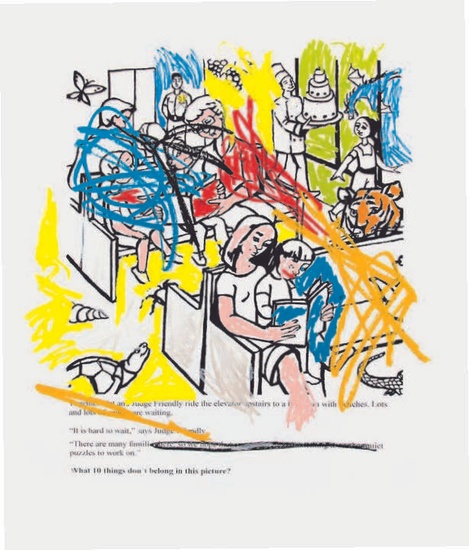

Sable Elyse Smith, Coloring Book 24, 2018. Screen printing ink and oil stick on paper, 60 x 50 inches. Courtesy of the artist; JTT, New York; and Carlos/Ishikawa, London.

Marjorie Anders, “Counties Turning to Privately Operated Jails,” Clovis News Journal, August 4, 1985.

For a more in-depth history of the origins of “crimmigration,” see César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández, “Creating Crimmigration,” Brigham Young Law Review 2013, no. 6 (February 2014): 1457–1515, https://digitalcommons. law.byu.edu/lawreview/vol2013/iss6/4; and Jonathan Simon, “Refugees in a Carceral Age: The Rebirth of Immigration Prisons in the United States,” Public Culture 10, no. 3 (Spring 1998): 577–607.

The Nation, “Corrections Corporation of America’s Founders Tom Beasley and Don Hutto,” video, 2:47, February 27, 2013, originally published on CCA’s website, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DAvdMe4KdGU.

A noteworthy coincidence: more than a decade later, in 1997, CCA bought another Olympic—the Olympic Hotel and Spa in Fallsburg, New York—for $470,000, in the hopes of expanding its operations to the Northeast. For more on this, see Lauren Brooke-Eisen’s Inside Private Prisons (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017), 103; and Steven Donziger, “The Hard Cell,” New York Magazine, June 9, 1997, 26–28.

Wayne King, “Contracts for Detention Raise Legal Questions,” New York Times, March 6, 1984, https://www.nytimes.com/1984/03/06/us/contracts-for- detention-raise-legal-questions.html.

Damon Hininger, “T. Don Hutto—The Mettle of the Man Behind Our Proud Facility,” Employee Insights, CCA, January 19, 2010, https://perma.cc/ G9ZZ-KVAJ.

Holly Kirby et al., The Dirty Thirty: Nothing to Celebrate about 30 Years of Corrections Corporation of America (Austin: Grassroots Leadership, 2013), 1. For more about the founding of the company, see Winthrop Knowlton’s case study Corrections Corporation of America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Kennedy School of Government Case Program, 1985).

Hininger, “T. Don Hutto.”

The corporate globalization and deindustrialization of this period—exacerbated in the 1990s with free trade agreements like NAFTA—was a force of impoverishment. The spaces of concentrated poverty, disinvestment, and joblessness left in the wake of America’s development path were met with attacks on welfare and social programs, with the War on Drugs, with “tough on crime,” with more police, and more prisons. Angela Y. Davis has described the racialized social crisis that emerged from this pattern of economic development and globalized capital: “In fleeing organized labor in the US to avoid paying higher wages and benefits, [corporations] leave entire communities in shambles, consigning huge numbers of people to joblessness, leaving them prey to the drug trade, destroying the economic base of these communities and thus affecting the education system, social welfare and turning the people who live in those communities into perfect candidates for prison. At the same time, they create an economic demand for prisons, which stimulates the economy, providing jobs in the correctional industry for people who often come from the very populations that are criminalized by this process. It is a horrifying and self-reproducing cycle.” See Angela Y. Davis, “Globalism and the Prison Industrial Complex: An Interview with Angela Y. Davis,” by Avery F. Gordon, Keeping Good Time: Reflections on Knowledge, Power, and People (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2016), 48–49.

Erik Larsen, “Captive Company,” Inc., June 1, 1988, https://www.inc.com/ magazine/19880601/803.html.

James Austin and Garry Coventry, Emerging Issues on Privatized Prisons (Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Assistance, 2001), 15, https://www. ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/bja/181249.pdf.

Larsen,“CaptiveCompany.”) CCA’s operational efficiencies, no matter how small, are a part of the company’s larger cost-saving efforts to reduce the labor of managing its facilities through design. In fact, the provisional “design elements”—cyclone fence, barbed wire, bamboo, sand, exterior locks, iron bars—working to turn the Olympic Motel into a site of captivity also worked to undermine the conventional image of corrections.[](footnote “CCA rebranded as CoreCivic in October 2016. According to the company today, “Many of the once iconic symbols of correctional facilities that required substantial staffing, such as high concrete perimeter walls and even higher guard towers, have been rendered obsolete by modern technologies. Yet, such structures still exist at many government-owned correctional facilities across the country. CoreCivic’s design elements can create meaningful short- and long-term savings, while improving facility safety and security.” See CoreCivic, *ESG Report: Environmental, Social and Governance 2018, 17.

Codified in 8 C.F.R. SS 212.5, 235.3. See Michael Welsh, “The Immigration Crisis: Detention as an Emerging Mechanism of Social Control,” in “Immigration: A Civil Rights Issue for the Americas in the 21st Century,” ed. Susanne Jonas and Suzie Dod Thomas, special issue, Social Justice 23, no. 3 (Fall 1996): 170.

According to a report produced by the US General Accounting Office in 1992: “INS can detain about 99,000 aliens a year at its current facilities. However… about 489,000 aliens were subject to detention between 1988 and 1990 because they were criminal, deportable, or excludable. INS has released criminal aliens and not pursued illegal aliens because it did not have the detention space to hold them.” United States General Accounting Office, Immigration Control: Immigration Policies Affect INS Detention Efforts, report to the Chairman of the United States Senate Committee on Judiciary Subcommittee on International Law, Immigration, and Refugees (Washington, DC, 1992), 3. See also Welsh, “The Immigration Crisis,” 170.

César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández, Migrating to Prison: America’s Obsession with Locking up Immigrants (New York: New Press, 2019), 63.

Sara Ahmed, What’s the Use? (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), 22–23.

Over 90 percent of individuals are held in public prisons. See Wendy Sawyer and Peter Wagner, “Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2020,” Prison Policy Initiative, press release, March 24, 2020, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/ reports/pie2020.html.

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “The Worrying State of the Anti-Prison Movement,” Social Justice, February 23, 2015, http://www.socialjusticejournal.org/the- worrying-state-of-the-anti-prison-movement.

City of Los Angeles v. Patel, 576 US_(2015), dissent, 1, https://www. supremecourt.gov/opinions/14pdf/13-1175k537.pdf.

Wang writes this specifically about the supposed “race neutrality” of PredPol, a predictive policing software that focuses its crime data on time and location rather than on personal demographics. Though “PredPol is a spatialized form of predictive policing that does not target individuals or generate heat lists, spatial algorithmic policing, even when it does not use race to make predictions, can facilitate racial profiling by calculating proxies for race, such as neighborhood and location.” Typology can be added to this list of proxies. See Jackie Wang, Carceral Capitalism (South Pasadena: Semiotext(e), 2018), 249.

Patel, 576 US__, opinion of the court, at 14.

Ahmed, What’s the Use?, 23.

Here McKittrick is writing about, and quoting from, Octavia Butler’s Kindred—about how Dana Franklin, the young Black narrator and protagonist of Kindred, moves rather inexplicably between 1976 Los Angeles and antebellum Maryland, between her apartment and a plantation, between her present life and the life of her forebears. See Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 2. Butler elsewhere has said that time travel was “just a device for getting the character back to confront where she came from.” And yet, this device produces a new unstable and uneven terrain—a different “spatial story” that “hooks” and “stacks” spatially and temporally distinct sites into one. See Octavia Butler, “An Interview with Octavia Butler,” by Randall Kenan, Callaloo 14, no. 2 (Spring 1991): 496.

Avery F. Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 23, 24.

Holt v. Sarver, 300 F. Supp. 825 (E.D. Ark. 1969), https://www.clearinghouse. net/chDocs/public/PC-AR-0004-0006.pdf.

Holt v. Sarver, 300 F. Supp. 833.

Robert Sarver was ordered to report to the court within 30 days about the steps being taken the resolve the problems (i.e. unsanitary and inhumane isolation cells, no medical attention, and a total lack of protection and precaution against prisoner assault).The court did not find his report and progress adequate.

Holt v. Sarver, 309 F. Supp. 362 (E.D. Ark. 1970), https://law.justia.com/cases/ federal/district-courts/FSupp/309/362/2096340.

See her conversation with Avery F. Gordon, “Globalism and the Prison Industrial Complex: An Interview with Angela Y. Davis,” 52. I am also thinking of Nikhil Pal Singh’s description of “exceptional zones of armed appropriation”: “The latter are domains not only for enacting plunder, that is, primitive accumulation (or accumulation by dispossession), but also for developing cutting-edge procedures, logics of calculation, circulation, abstraction, and infrastructure—the slaver’s management of human cargo, the camp, the prison, the forward military base—innovations that can proceed insofar as they are unfettered by legally protected human beings advancing new prejudices, built upon the old.” Emphasis added. In Singh, “On Race, Violence, and So-Called Primitive Accumulation,” Social Text 34, no. 3 (September 2016): 41.

Jane Zimmerman, “The Convict Lease System in Arkansas and the Fight for Abolition,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 8, no. 3 (Autumn 1949): 177.

See Edmond Urquhart’s entry in Henry Hall, ed., America’s Successful Men of Affairs: An Encyclopedia of Contemporaneous Biography, vol. 1 (New York: The New York Tribute, 1895), 667. For sale of land, see Jobe v. Urquhart, 102 Ark. 470 (1912).

Amy Cluckey and Jeremy Wells, introduction to “Plantation Modernity,” ed. Cluckey and Wells, special issue, The Global South 10, no. 2 (Fall 2016): 1–10.

It should be said that the Arkansas prison system had by this time been under intense scrutiny for years. The so-called reform era of 1967–1968 was driven by Governor Winthrop Rockefeller under Thomas O. Murton, who found hundreds of skeletons buried on Cummins Prison Farm. See Thomas O. Murton and Joseph Hyams, Accomplices to the Crime: The Arkansas Prison Scandal (New York: Grove Press, 1969).

For more on the “ideal goals for southern penology,” see Blake McKelvey, “A Half a Century of Southern Penal Exploitation,” Social Forces 13, no. 1 (October 1934–May 1935): 114.

Holt v. Sarver, 309 F. Supp. 370.

For a prolonged legal parsing of the Thirteenth Amendment, see Michele Goodwin, “The Thirteenth Amendment: Modern Slavery, Capitalism, and Mass Incarceration,” Cornell Law Review 104, no. 899 (2019): 900–975, https://www.lawschool.cornell.edu/research/cornell-law-review/Print- Edition/upload/Goodwin-final.pdf.

In regards to this string of “differences”: Many scholars, including Ruth Wilson Gilmore and James Kilgore, have written extensively on the myth of the contemporary prison as a site of labor exploitation—reframing the prison’s relation to labor according to incapacitation, idleness, underwork, and boredom, which in turn has prompted analyses of the prison as a ware- house for dealing with surplus populations. For an incredibly clear and succinct discussion between the two on captive labor forces today, see Ruth Wilson Gilmore and James Kilgore, “Some Reflections on Prison Labor,” The Brooklyn Rail, June 2019, https://brooklynrail.org/2019/06/field-notes/ Some-Reflections-on-Prison-Labor; and James Kilgore, “The Myth of Prison Slave Labor Camps in the US,” CounterPunch, August 9, 2013, https:// www.counterpunch.org/2013/08/09/the-myth-of-prison-slave-labor- camps-in-the-u-s. For more on the hermeneutic of racial capitalism and on the racial dimensions of dispossession (body) and expropriation (land), see the “Gratuitous Violence” section in the introduction of Wang, Carceral Capitalism, 85–95, as well as pages 99–126.