A

1172 Amsterdam Avenue

New York, New York 10027

1172 Amsterdam Avenue

New York, New York 10027

1172 Amsterdam Avenue

New York, NY 10027

B

C

D

1172 Amsterdam Avenue

New York, NY 10027

E

F

G

H

I

N

O

1172 Amsterdam Avenue

New York, NY 10027

P

1172 Amsterdam Avenue

New York, New York 10027

R

S

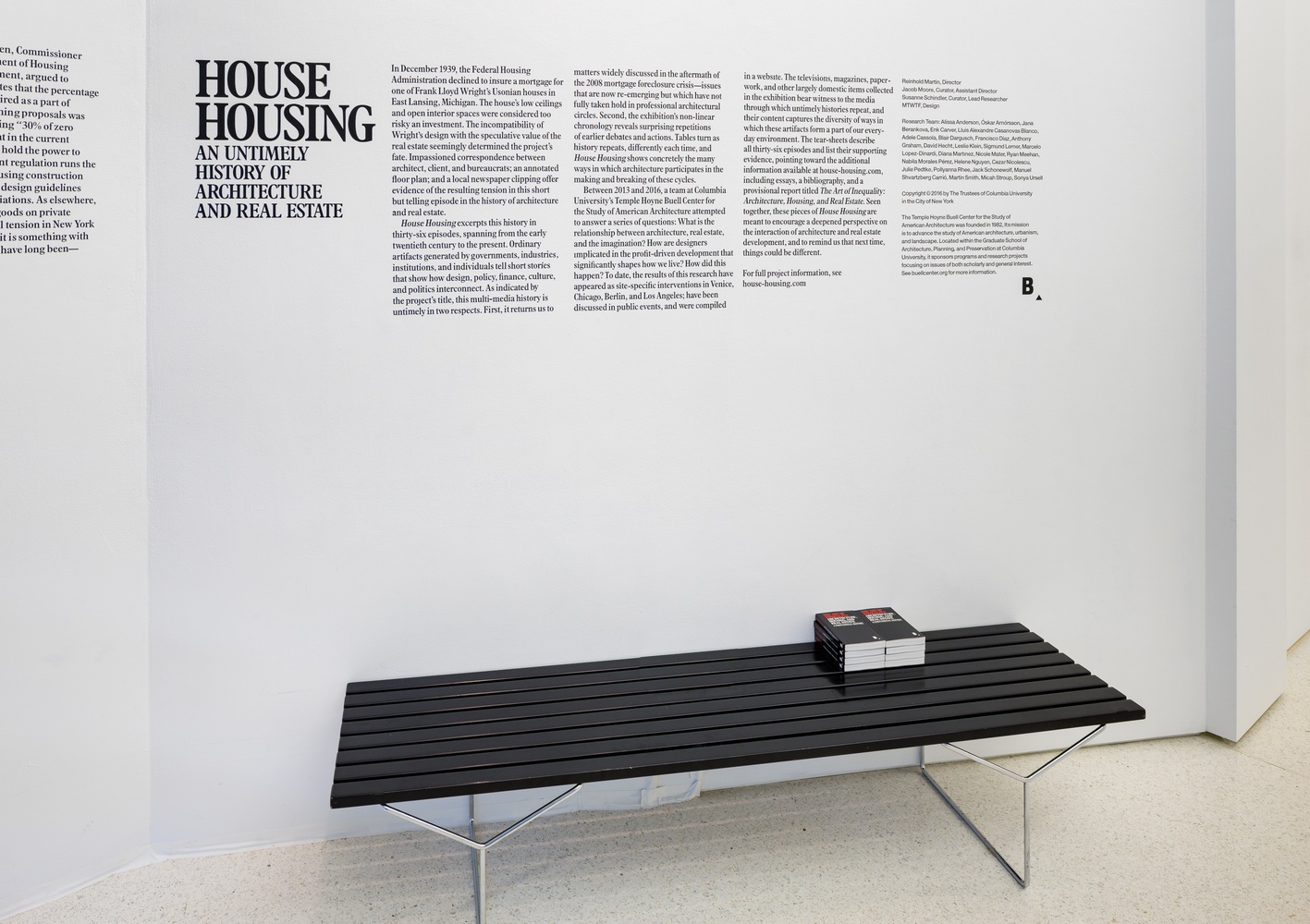

House Housing: An Untimely History of Architecture and Real Estate

In February 2016, Vicki Been, Commissioner of New York City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development, argued to affordable housing advocates that the percentage of affordable housing required as a part of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s rezoning proposals was as good as it could get. Saying “30% of zero is zero,” Been indicated that in the current system, private developers hold the power to build, and that too-stringent regulation runs the risk of eliminating new housing construction altogether. Adjustments to design guidelines were central to these negotiations. As elsewhere, the dependence of public goods on private capital constitutes a central tension in New York City’s housing debate, and it is something with which architects are—and have long been— very familiar.

~

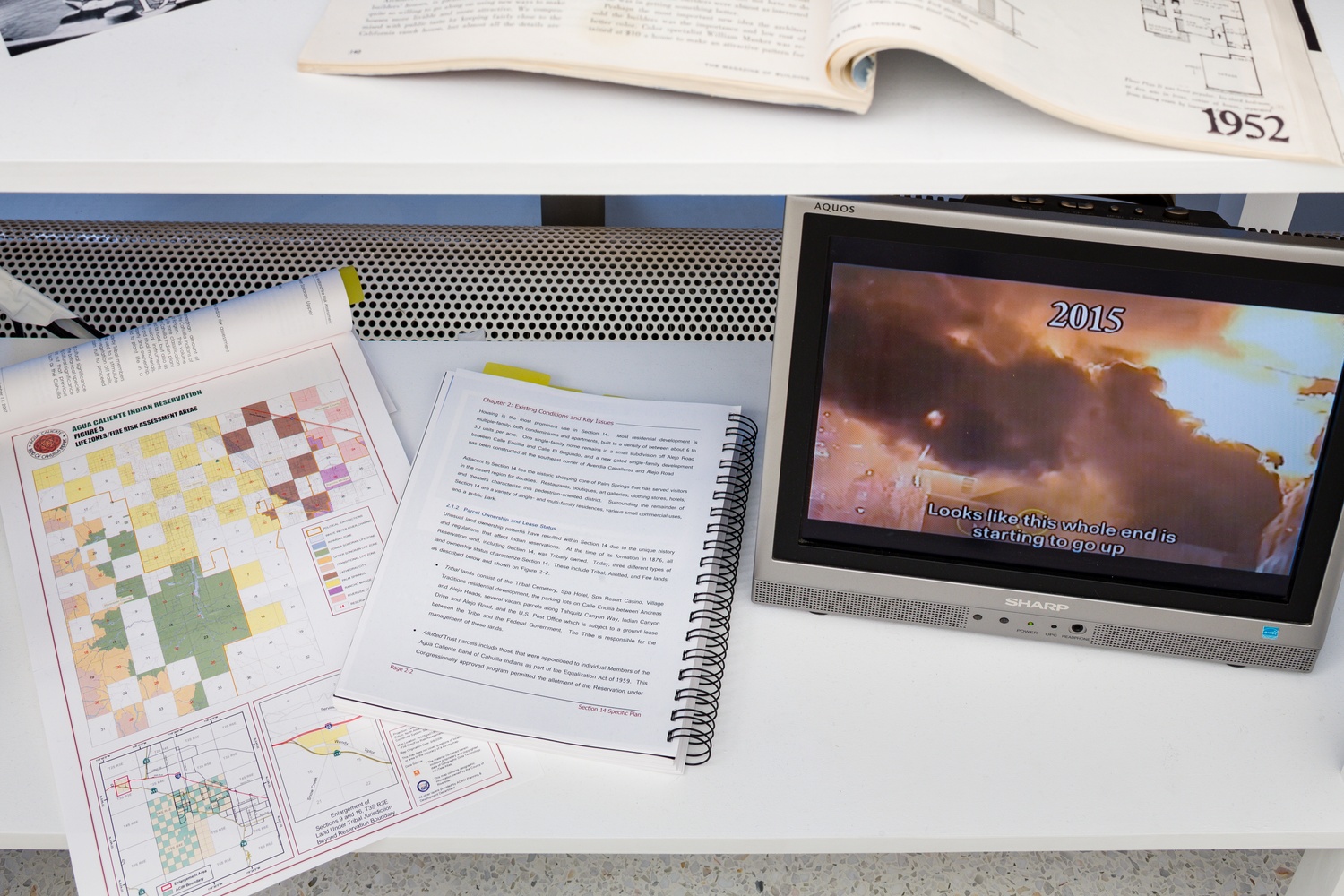

In December 1939, the Federal Housing Administration declined to insure a mortgage for one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian houses in East Lansing, Michigan. The house’s low ceilings and open interior spaces were considered too risky an investment. The incompatibility of Wright’s design with the speculative value of the real estate seemingly determined the project’s fate. Impassioned correspondence between architect, client, and bureaucrats; an annotated floor plan; and a local newspaper clipping offer evidence of the resulting tension in this short but telling episode in the history of architecture and real estate.

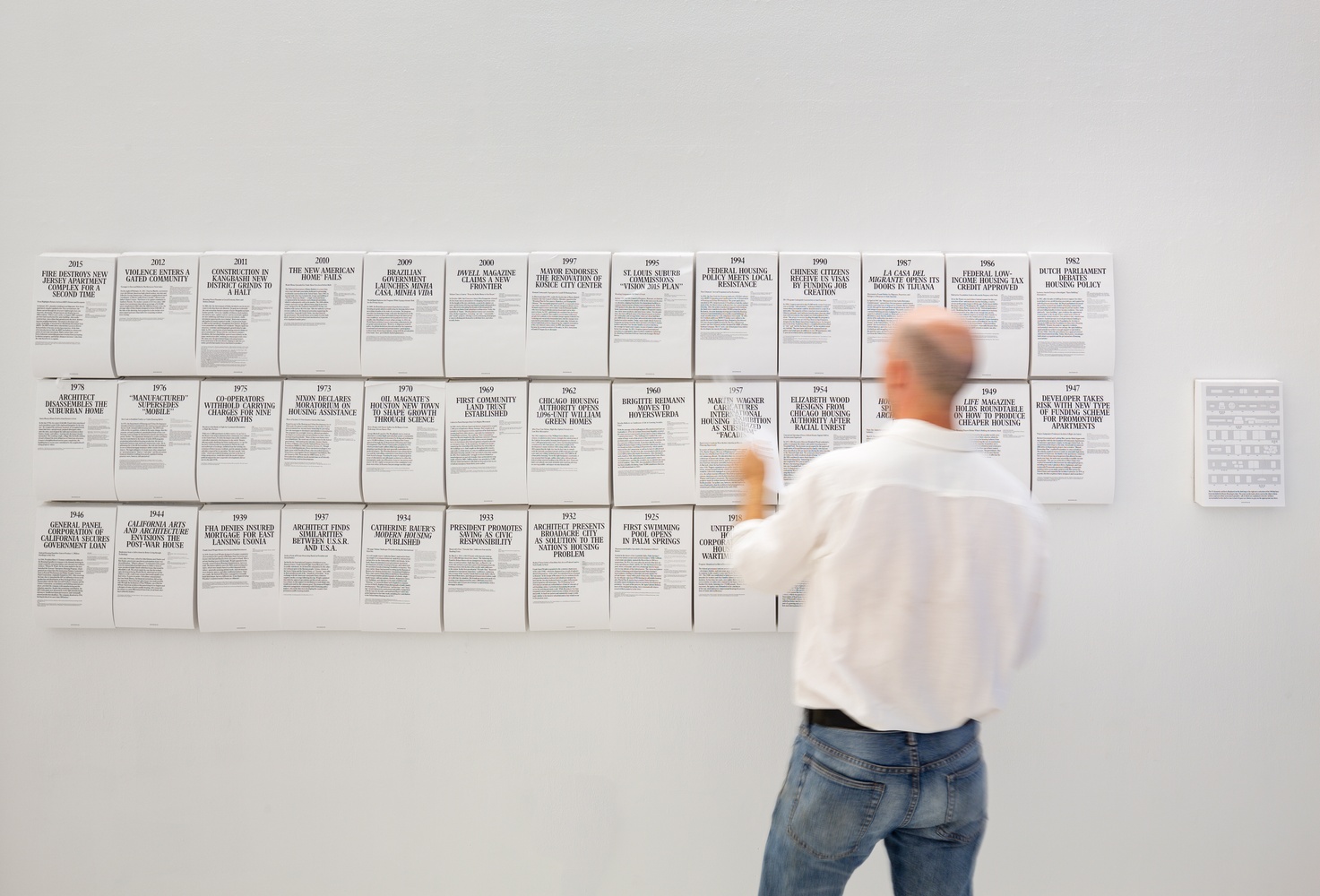

House Housing excerpts this history in thirty-six episodes, spanning from the early twentieth century to the present. Ordinary artifacts generated by governments, industries, institutions, and individuals tell short stories that show how design, policy, finance, culture, and politics interconnect. As indicated by the project’s title, this multi-media history is untimely in two respects. First, it returns us to matters widely discussed in the aftermath of the 2008 mortgage foreclosure crisis—issues that are now re-emerging but which have not fully taken hold in professional architectural circles. Second, the exhibition’s non-linear chronology reveals surprising repetitions of earlier debates and actions. Tables turn as history repeats, differently each time, and House Housing shows concretely the many ways in which architecture participates in the making and breaking of these cycles.