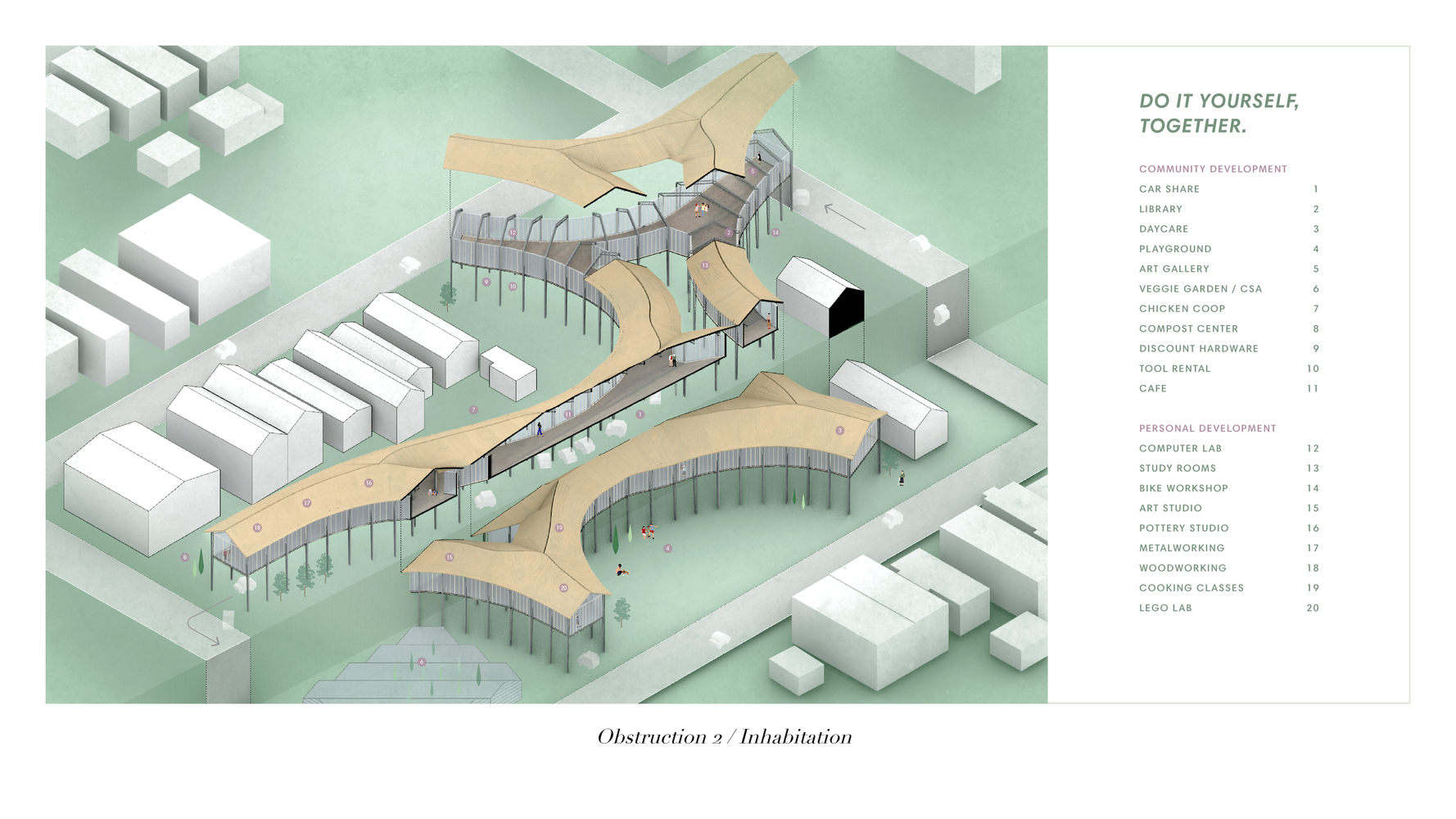

Buildings are prescriptive as opposed to facilitative. Whether new construction or renovation, a building begins its life as a sea of possibilities. In the process of planning, design, and construction, potential fates are lost and others discovered. In the end, what’s left is a creation with a singular history, static qualities, and a cohesive narrative about its purpose and role in the world. Even when evolution is baked into a project from the start, adaptable systems become rigid and prescriptive in their translation from idea to physicality. There is magic to a space which, despite its materiality and specificity, remains charged with the sense that anything is possible. But how is this condition achieved? How does a building maintain its “blank-canvasness” and simultaneously come to life in specific ways? Solution #1: Retrofit a relic. By rehabilitating a forlorn warehouse or factory, the architect benefits through inheriting a pre-painted canvas. By designing in concert with an existing set of spatial, material, and circulatory features, the final building is not a finished product, but a physical record of a dialogue which took place. The space is therefore enlivened with a sense of play and possibility, as visitors float between the walls of a conversation perhaps unfinished. Solution #2: Co-opt a structural system to generate highly specific and inventive objects, then set about occupying them. Yirmiyahu Gilbert

A

AIA CES Credits

AV Office

321M Fayerweather Hall

Abstract Publication

415 Avery Hall

Academic Affairs

400 Avery Hall

Academic Calendar, Columbia University

Academic Calendar, GSAPP

Admissions Office

407 Avery Hall

1172 Amsterdam Avenue

New York, New York 10027

Advanced Standing Waiver Form

Must be printed and returned to 400 Avery Hall

Alumni Board

Alumni Office

405 Avery Hall

1172 Amsterdam Avenue

New York, New York 10027

Architecture Studio Lottery

Assistantships

Avery Library

300 Avery Hall

1172 Amsterdam Avenue

New York, NY 10027

Avery Review

Avery Shorts

B

Black Student Alliance at Columbia GSAPP

Building Science & Technology Waivers

Bulletin Archive

C

Career Services

300M Avery Hall

Columbia Books on Architecture and the City

Commencement

Communications Office

415 Avery Hall

Conversations podcast

Counseling and Psychological Services

Courses

Credentials Verification

Credit Transfer

Cross Registration

D

Dean’s Letter

Dean’s Office

402 Avery Hall

1172 Amsterdam Avenue

New York, NY 10027

Development Office

404 Avery Hall

Directory of Classes (All Columbia University)

Disability Services

Dodge Fitness Center

3030 Broadway Dodge

Dual Degree Program Requirements

E

End of Year Show

Events Office

415 Avery Hall

External Funding Sources

F

Faculty Directory

Feedback

Finance Office

406 Avery Hall

Fitch Colloquium

Future Anterior Journal

G

GSAPPX+

Grades

Graduation

Graphics Project

H

Honor System

Human Resources

Hybrid Pedagogy Resources

I

IT Helpdesk Ticket, GSAPP

IT Office, GSAPP

IT, Columbia University (CUIT)

Identity

International Students and Scholars Office (ISSO)

N

News and Press Releases

Newsletter Sign Up

Non-Discrimination Statement and Policy

O

Onera Prize for Historic Preservation

Online Admissions Application

GSAPP Admissions 407 Avery Hall

Output Shop

116 Avery Hall

1172 Amsterdam Avenue

New York, NY 10027

Ownership of Student Work Policy

P

Paris Prize, Buell Center

Paul S. Byard Memorial Lecture Series

Percival & Naomi Goodman Fellowship

Plagiarism Policy

Policies & Resources

Press Releases

Publications Office

415 Avery Hall

1172 Amsterdam Avenue

New York, New York 10027

R

Registration

Registration: Add / Drop Form

Room Reservations

S

STEM Designation

Satisfactory Academic Progress

Scholarships

Skill Trails

Student Affairs

400 Avery Hall

Student Awards

Student Conduct

Student Council (All Programs)

Student Financial Services

Student Health Services at Columbia

Student Organization Handbook

Student Organizations

Student Services Center

205 Kent Hall

Student Services Online (SSOL)

Student Work Online

Studio Culture Policy

Studio Procedures

Summer Workshops

Support GSAPP

Object ➔ Building?