Introduction

Advanced Architecture Studio VI

In the Spring 2021 semester, the 18 studios of the Advanced Architecture Studio VI course addressed an ambitious scope of concerns, considered in relation to architecture’s social, material, environmental, and political potentials, with projects ranging from communal kitchens for co-housing apartment buildings, to adaptations of an abandoned factory as civic infrastructure, to pavilions for a prison-based educational institution. In contrast to previous semesters, many of the studios considered sites in New York City and the surrounding region, with projects located throughout the city’s neighborhoods: the North Bronx, Edgemere and Jackson Heights in Queens, Crown Heights and Sunset Park in Brooklyn, and Washington Heights in Manhattan, and from Morningside Park, just steps from Avery Hall, to the larger region, with projects sited in Patterson, New Jersey and the Hudson River Valley.

While prompted by limitations imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, this rapprochement with New York and its environs allowed students and faculty to engage the social and political conditions of the city, with studios addressing urban migrations and displacements, care and belonging, and the claiming and contesting of space through monuments, institutions, and infrastructures. Many studios took advantage of the geographic proximity, often combined with remote forms of communication, to develop dialogues with local community-based organizations, while other studios used the shift to virtual encounters, necessitated by the pandemic, to assemble an international network of collaborators.

Tracing a through-line across the various studios, sites, and approaches, students and faculty developed a shared conversation in the series “Unlearning Whiteness,” with a group of distinguished guest speakers that included theorist Jack Halberstam, designer Mary Ping, artist Mel Chin, and political scientist Achilles Kallergis. These sessions considered the political and ethical imperatives of architecture and urbanism as they intersect with questions of subjectivity, labor, ecology, and migration.

Throughout the semester, students and faculty navigated the ever-shifting effects of the global pandemic, which required agile approaches to the collective work of each studio and to the sites, actors, and programs considered in their designs. In the context of the pandemic, the studios affirmed the potentials of architecture as a sociopolitical project, one that is committed to the city and its communities yet remains open to uncertain futures.

Advanced Architecture Studio VI TA: Maxim Kolbowsky-Frampton

1

Reimagining the Industrial Waterfront

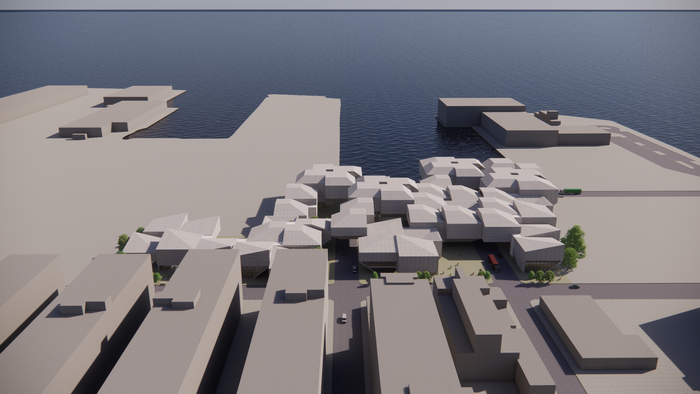

In the studio Reimagining the Industrial Waterfront: Utica’s Harbor Point, students develop components of a vision for a new mixed-use community on a remediated 100-acre waterfront site located alongside the historic harbor in Utica, New York, a once-booming industrial city located 95 miles west of Albany. The “client” is the Harbor Point Development Corporation, an entity created by the government to facilitate development by issuing design guidelines, overseeing a competitive procurement process, and crafting the public-private partnership that will unlock value at this formerly industrial waterfront site. The students’ work is expected to serve as a foundation and inspiration for the development guidelines moving forward. The studio site offers challenges and opportunities. Areas around Harbor Point suffer from chronic flooding due to its location in a Mohawk River floodplain; students are asked to consider ways to address this resilience issue as part of their work.

Students: Thomas Abreu, Tomas Buitrago, Brandon Conrad, Marie Christine Dmitri, Jindian Fu, Shamkhal Hasanli, Keon Hee Lee, Spyro Jacobson, Mike Kolodesh, Qianyue Ma, Wanqi Sun

The development site is a 5-acre waterfront space, sitting between Delta Park and the post-industrial-style warehouse to the south. As section B in the third phase of the Harbor Point Master Plan 2021, Mohawk Landing will provide 23,486 SF of retail spaces, 13,859 SF of office, and 108,937 SF of residential apartments (146 units). Divided into southern and northern sections, Mohawk Landing will be constructed separately and will be completed phase by phase to achieve financial feasibility. After applying to the LIHTC program, this project can generate a 10-year IRR at 11.89% and 1.68x Equity Multiple. This mixed-use development is designed into a transitional fusion style to better harmonize this community. By providing 69,000 SF of open space in front of the water, Mohawk Landing will create a lively community and provide the residents an interactive living style in all four seasons.

When designing this project, we took into account numerous factors that would affect both Harbor Point and Utica in general. The project had to be both cost-effective due to Utica’s sensitive residential market price and consistent with Harbor Points waterfront nature. This project’s success would lead to the future development of Harbor Point, so we focused on numerous aspects like unit mix, design, and uses of the buildings. Focusing mainly on the affordable residential complexes, we tried to address the area’s population problem and offer the residents cheap but modern living alternatives. We had to take into account the fact that Utica’s residential market is itself on affordable housing, so we had to keep our development and rental costs in a limited amount. Throughout the planning stage, we focused on the following objectives: To increase pedestrian foot traffic to Harbor Point; Develop new affordable residential complexes with Utica prices; Develop public spaces to attractive for residents; To start economic activity in Harbor Point.

The Utica Harbor Point Project aims to link the historic inner harbor along the Mohawk River and Erie Canal to the greater ecosystem of Utica, NY. Our team is considering a three-phased approach. Phase A will begin with the development of a Park along the long axis of the site, Phase B will consist of mixed-use development, and Phase C will add a residential component. This joint effort between the private and public realms will result in an innovative development that will revitalize Harbor Point and add to the history of the area. Today, our Development Team is focusing on Phase B, a proposal of 75 affordable housing units, 75 market-rate units, and 24,000 SF of pure commercial and residential space. Due to high levels of demand resulting from anticipated growth in population and employment, along with planned new developments in the area, the proposed development of the site aims, not only to fulfill a housing need but also to embark on a new urban dimension for Utica’s historic Harbor Point. Through low-income housing tax credits (LIHTC), equity, and debt, the Development Team will look to revitalize the area by developing a new state-of-the-art facility for community members to live, work, and play.

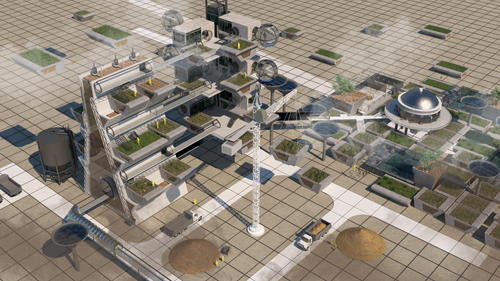

Acting as a catalyst for both Utica and the Mohawk River Valley, the Harbor Point Redevelopment will create a new beacon of energy within the city. The development will contain programs that include: affordable residential units, market-rate residential units, retail spaces, community facilities, structured parking, an extended stay hotel, office space, and an urban market with stalls. The different building typologies are placed on a gradient from public commercial use to a quieter private residential use. Social equity was a crucial part of the development, so we defined many of the programs around helping the large refugee population in Utica. This was done through setting aside affordable units, housing local nonprofits in the community facilities, and setting aside stalls in the market. Architecturally, the project is heavily defined through using engineered wood as both a building material and an architectural expression. Alongside a concrete podium, this allows for the residential buildings to cantilever, giving residents the impression of floating over the adjacent harbor and park. Blending distinct programs and architectural interventions allows this project to be financially successful as well, boasting an 18.8% levered IRR and a 4.34 equity multiple over a 15-year holding period.

Confluence at Harbor Point acts as a socially equitable beacon of attraction. The project consists of four mix-used and mid-rise buildings. The first building consists of a commercial entity with a fast-food restaurant on the ground floor, a theater on the first floor, and office spaces on the third and fourth floors. The idea to place this large complex towards the end of Harbor Point aims to encourage people to use the available promenade. The three remaining buildings encompass commercial and community spaces such as a gym, market, gallery spaces, and an early education facility. Market-rate housing is flanked by two affordable housing buildings. In fact, two bridges allow a physical connection between the affordable and market-rate housing units, providing communal spaces such as laundry rooms, offices, lounge areas, and outdoor balconies to be shared by all residents. The ground floor and commercial building mimic the industrial outlook that is found in Utica. Since most buildings in the area consist of low-rise buildings, the human scale and relationship to the street are of high importance. The residential buildings incorporate a more minimalistic stucco finishing. As for the market-rate building, the individual balconies and planters are key architectural features.

Mohawk Landing: Utican Utopia

The development site is a 5-acre waterfront space, sitting between Delta Park and the post-ind...

Reimagining the Industrial Waterfront: Utica’s Harbor Point

When designing this project, we took into account numerous factors that would affect both Harb...

Utica Harbor Point

The Utica Harbor Point Project aims to link the historic inner harbor along the Mohawk River a...

Harbor Point Development

Acting as a catalyst for both Utica and the Mohawk River Valley, the Harbor Point Redevelopmen...

Confluence at Harbor Point

Confluence at Harbor Point acts as a socially equitable beacon of attraction. The project cons...

2

Everything Must Scale (5)

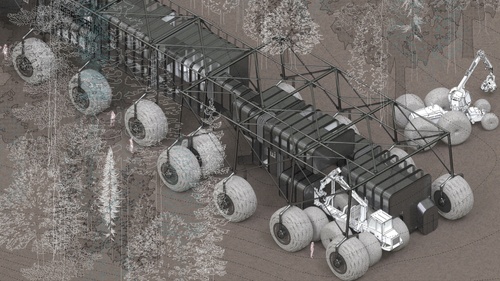

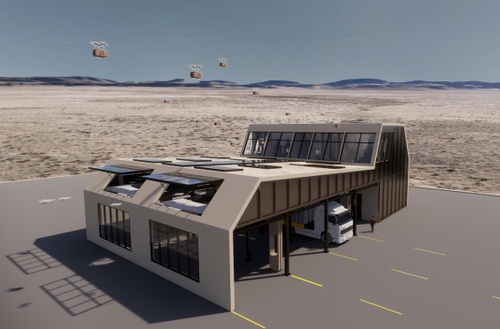

Everything Must Scale has been a working title organizing a series of studios that have explored a realm where architectural design is enacted at scale – in the economic sense of the term where commodities or services or even architecture are replicated over entire territories and as construction blocks of commerce and social organization. Some of these components are changing already; as a kind of precipice agent, they are a promise of more change. Perhaps the actual – the eventual more meaningful change, only possible with a chaotic still unclear ensemble of propellants. The studio Everything Must Scale (5): The Last Truck Stop explores one of these items with an eye towards how architecture can act as an enzyme to effect the wider field it participates in. Students design for scale but focus on the specifics of place, of site, and need – in effect see where architecture can scale.

Students: Fahad Al Dughaish, Rasam Aminzadeh, Noor Begum, Chao Chang, Jiyong Chun, Liwei Guo, Yao Hu, Seonggeun Hur, Wan-Hsuan Kung, Su Li, Ziyi Wang, Zihan Xiao

Plasticity in Future stop

My design is inspired by the term “plastic art”; it explores spatial plasticity an...

SYNC Construct

Early sociologists reflected that our society was a self-contained and self-regulating semioti...

Droneport Truckstop

With the observations of material, color, and motion as my focal points, this industrial and v...

3

A Pliable Place

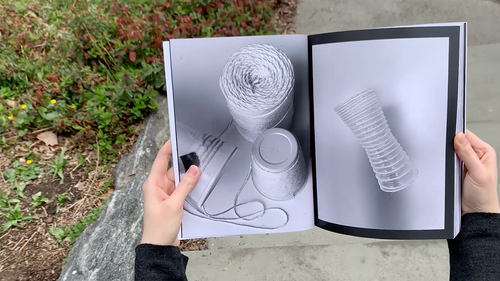

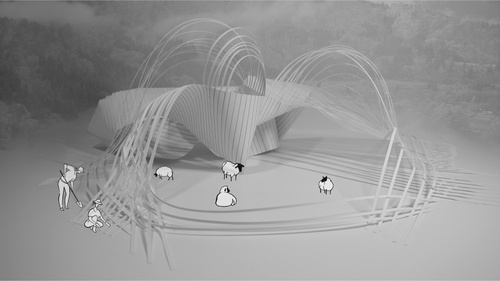

Products, furniture, and interiors all have the capacity for creating a sense of place and give meaning to the gathering of our communities. Although they are not architecture, they are, in fact, architectural in their contribution to the definition of our lives, homes, neighborhoods, and cities. This studio presents the challenge of fabricating our built environment using traditional craft techniques as inspiration that allows for a more pliable definition of surface, structure, and enclosure. Through the exploration of three universal objects as architecture, including a basket, a hut, and a village, students develop new approaches to making. Particular emphasis is placed on learning and sharing hands-on cross-cultural fabrication techniques to be as inclusive as possible of all global perspectives when considering architecture and the identities it serves.

Students: Zachary Bundy, Abhinav Gupta, Jasmine Jalinous, Zhenting Jiang, Susan Lee, Devansh Mehta, Ian Wach, Chia Jung Wen

“Analyzing and interpreting Anni Albers’ work, A Letter evolved from a weaving sample to a vessel, a partition, and an interior space. The design allows for different readings of the word ‘letter’ through flexible configurations and layers of interactions.”

SOFT architecture

This project comprises a series of explorations that take as a starting point Pasture by Anni ...

Strong Ties, Weak Ties

Starting from Anni Albers’ 1947 painting, Knot, I focused on exploring the gradient of the rel...

4

Taking up Space, Making Place

If, according to Eric Klinenberg in Palaces for the People, social infrastructure fosters a supportive community, rescuing residents when hard infrastructure fails and promotes a sense of belonging, community pride and, ultimately, civic engagement, and if, according to the New York City Street Design, programming streetways, sidewalks, public plazas, and other public space supports local businesses, connects residents with resources, builds community and “encourag[es] local ownership of the public spaces in which they occur,” how can we create public space that anchors Black immigrants to the Bronx? How can we create a place that takes into account their need to maintain and pass on their cultural distinctiveness while allowing them to fully realize their new identities? The studio Taking up Space, Making Place: Bronx Edition walks the Bronx, engages residents and local business owners, and imagines different urban futures that challenge ideas of inside and outside while creating event spaces in the streets that support the layered history of the place and the people.

Students: Angel Castillo, Chiun Heng Chou, Nelson De Jesus Ubri, David Musa, Urechi Oguguo, Zhijian Sun, Yueyang Wang, Jiayue Xu

Wrap It Up!

The Williamsbridge Workshop is a community-centered initiative where underserved young adults ...

Open Street Stories

Open Street Stories aims to leverage the Open Street program framework to create a network of ...

Recreation Center

Though there is a large population of young people living in the Williamsbridge area, there ar...

A Saturday Morning Ritual: A Space for Re-Membering

A Saturday Morning Ritual: A Space for Re-Membering” focuses on centering and celebrating blac...

Heterogeneous Platform

Big versus small is an eternal argument for humanity, especially in the political and cultural...

5

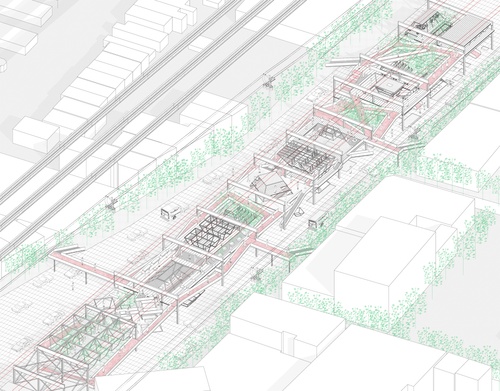

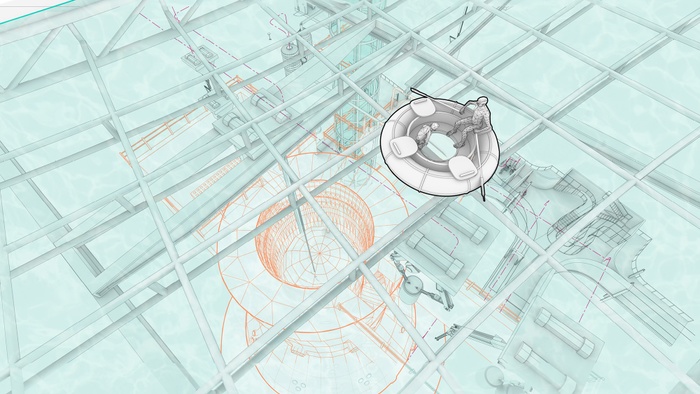

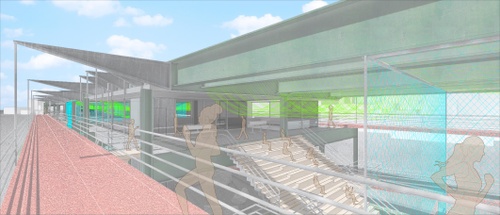

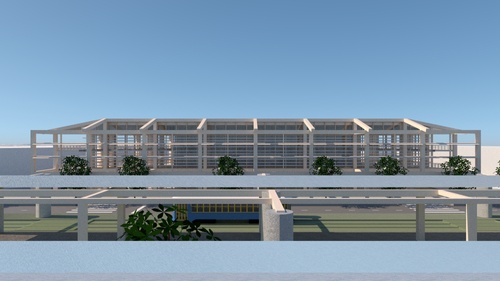

One Barn Five Obstructions

This studio investigated the architectural potential of pre-engineered buildings as a new civic magnet in the seaside neighborhood of Edgemere, Queens. Students worked to explore how architects might respond to a host of needs brought to the fore in the last year—bending a disciplinary tool around our unique socio-political situation while working through detailing and assembly. The studio engaged a real site, building system, community and consultants to explore the intersections between architecture and public agency.

To mine the potential of these building types, students worked through an iterative method, revisiting their designs over the course of the semester. Borrowing from Lars von Trier’s Five Obstructions, projects developed over a range of trials—from working as another designer (impersonation) to inventing program (inhabitation), considering assembly (installation) and performance (comfort). Ultimately, students combined these into a hybrid position (hypothesis), reflecting an attitude towards the discipline in their final semester, as the subject of their inquiries shifted into focus.

Students: Shuang Bi, Anirudh Chandar, Greta Crispen, Jacob Gilbert, Rahul Gupta, Charlotte Sie W Ho, Kassandra Lee, Chengjie Li, Sixuan Liu, Adela Locsin, Reem Yassin, Elie Zeinoun

OBSTRUCTION 1

OBSTRUCTION 2

OBSTRUCTION 3

OBSTRUCTION 4

OBSTRUCTION 5

6

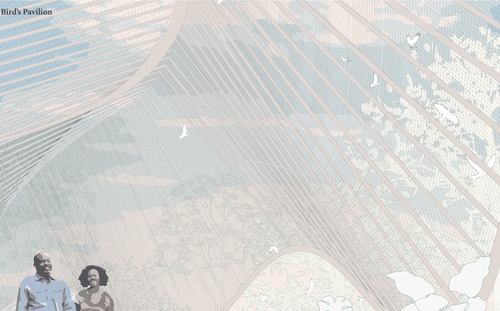

Migrations: Bodies in Movement

This studio is informed by the history of radical thinking about 20th-century architecture yet looks beyond, to the manner of space-making by Indigenous Peoples and Black bodies throughout the diaspora who have creatively appropriated various aspects of the landscape and built environment to invent new uses, programs, and forms of visibility. Furthermore, the studio presents an experimental curriculum deploying methodologies from the visual arts as well as theories of geography, infrastructure, and geology, to initiate dialogues about spatiality in an era of global crisis and the convergence of human-induced climate change, pandemic, and social justice revolution. Each student conducts preliminary research into the migration of different species (human, animal, insects) induced by climate change; the search for freedom and spatial justice; or biological response to changes in ecological systems. Each student then proposes a design intervention at the site of the historic Hinchliffe Stadium in Paterson, New Jersey on the escarpment above Paterson’s National Historic Great Falls to consider a project for environmental liberation.

Students: Abdelrahman Albakri, En-Ho Chan, Ying Cheng, Miranda Herpfer, MinJae Lee, Mariami Maghlakelidze, Hemila Rastegar-Aria, Skylar Royal, Xiaoliang Ying

What are the possibilities of thinking about architecture as an archaeological site? We need a disruption. A set of conditions are harmonized around the site. Utopia and heterotopia being implemented (the chemistry of the crowd forming a certain condition of heterotopia outside the stadium). Different interventions are assembled and come together with the issue of memory and time. The project celebrates the geographic uniqueness of the Hinchliffe site, which is strategically positioned on the edge of the vertical drop of the terrain, fulfilling the dual function of turning to the landscape while facilitating access to it from the flat terrain platform.

“This proposal aims to provide a space for people who suffer a huge level of stress or damage; it supports repair and rest both physically and mentally through individual and private meditation rooms, as well as counseling rooms for residents to release their stress.”

Paterson Learning Center - Passing Knowledge to the Next Generation

The ethnically and culturally diverse city of Paterson and the site of Hinchliffe Stadium in N...

“My thesis, in a word, is that we can make positive tension at the site by creating communal spaces that people want to inhabit—spaces that possess utility for them. My goal is to replicate the Great Fall: to draw people in on aesthetic grounds because the grounds provide a resource that all can construe as their own.”

“(em)powermist analyzes the intersection of water, technology, and race and their migration at the molecular scale in order to provide information to create layered spaces of education and liberation to return to at the environmental scale.”

7

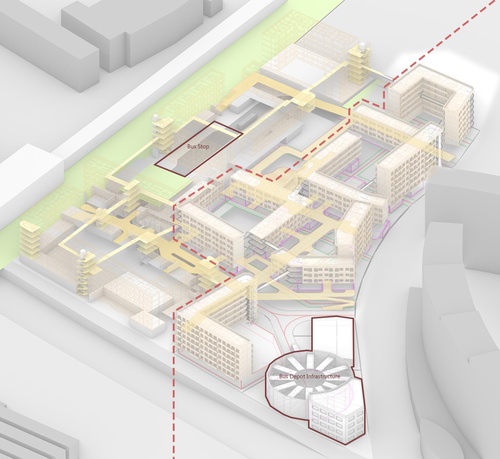

Hybrid Residential Infrastructure in Harlem for “Living Together”

Beyond the usual operating from scratch, or refurbishing buildings by preserving their core and shell, the management of existing structures and the built environment at large arises as a great battlefield of the future of the (existing) city. This agenda, a design problem in itself, demands going beyond conventional architectural strategies and developing more comprehensive, integrated, and open big-scale approaches. Previous studios, under the umbrella of “Typological Corrections,” have explored case studies located in central and consolidated areas of the city that are either in a bad condition, infra-utilized, or significantly vacant, to offer them a second chance. This semester, the studio focused on social housing developments commonly referred to as the “Projects” in Harlem, New York City.

Students: Maxwell Chen, Gabriela Franco, Nanjia Jiang, Sungmin Kim, Fan Liu, Mia Mulic, Brian Turner, Haoran Xu

The tower in the park typology provides unpleasant, unsociable, and segregated experiences of living while disconnecting from the surrounding context with homogeneous architecture. Commonscape activates the domestic and public realm with an array of activities that connects people and provides comfort at all scales. The shared space reimagines the corridor as an activated street, offering the experience of the street of walking through multiple programs. The façade of the building utilizes the system of stairs not only as an expression of multiplicity but also as a tool for connecting people with similar interests. The ground levels create street-like conditions with industrialized construction methods and encourage local occupancies. Through the typological correction, both the private and common spaces are activated with increased visibility and diversity, inviting families, residents, and the neighborhood to find meaningful connections within this new housing complex.

Harlem’s NYCHA subsidized housing projects are hybridized through tower bridging and refurbishment that support civic action and skill-building, while providing shops and spaces for community economic development. The new Wagner Houses integrate the industrial and domestic realms with experimental live-work-learn co-ops to address isolation, unemployment, and unaffordable housing, while allowing residents to earn wages and build creative businesses as they build their efficient collective homes.

My main project focus is open space on the ground floor of a NYCHA building. At the moment, a large amount of it is not actively used by the residents of the block or even the general public. This is mainly because it is just a big open field with nothing to interact with; there are only residential units and storage units. The project objective is to make better use of the ground floor open space it occupies and improve interactions occurring within.

8

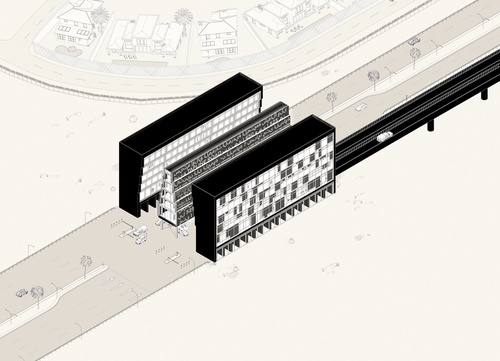

Factory

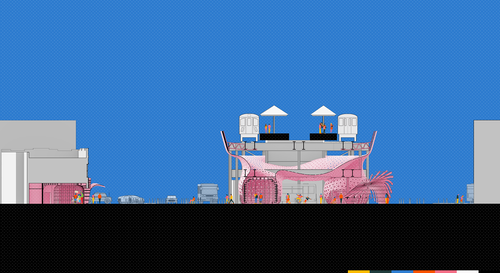

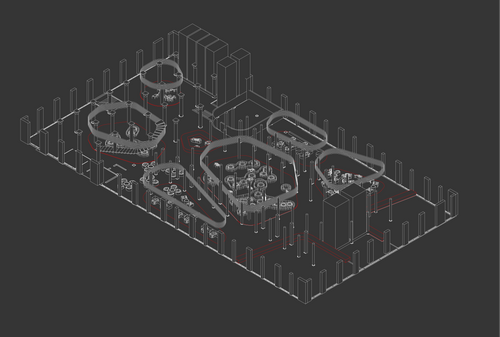

This studio reconsiders the entire Bush Terminal complex, located on the Brooklyn waterfront in Sunset Park, and envisions a new future for it as a center for new industries. Students are asked to design an urban factory complex or infrastructure that creates collective spatial structures for the manufacturing of artifacts and the shaping of exchanges. The work requires critical engagement with the many historical, social, economic, and technological contexts surrounding labor issues and influencing the design of factories. Students are challenged to conduct critical research and re-frame these conditions as innovative spatial formats for manufacture in their architecture.

Students: Tamim Aljefri, Yasmin Ben Ltaifa, Yuan Chen, Ali Elsinbawy, Yipeng Liu, Konstantina Marinaki, Magdalena Valdevenito, Lewei Wang, Eunjin Yoo, Charlotte Yu, Duo Zhang, Zixiao Zhu

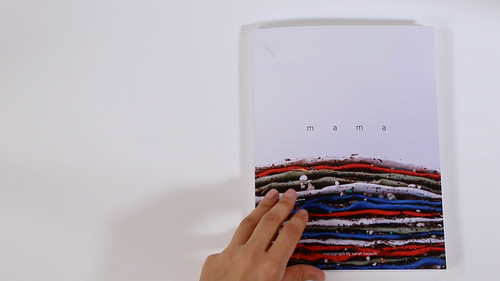

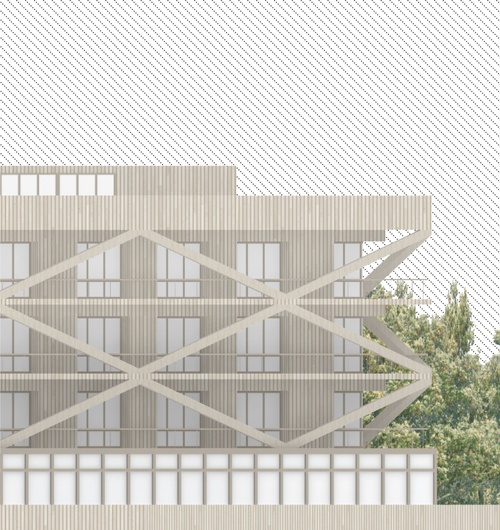

REFAB Factory in Bush Terminal adopts a circular “Take, Make, Reuse” attitude. The factory gathers pre- and post-consumer waste; creates jobs through mending, artisanal upcycling, natural dyeing, and material-tracking; and gives the garments a second life as respun fabric for local designers, recycled insulation for adjacent warehouses, and so on. REFAB conveys textiles through its thickened mass timber filigree both on the façade and in the interior. Interior volumes increase in size in the higher stories, finding their expression in the façade. Floorplates cross over each other, allowing for visual connections between production and relief spaces. In REFAB, the factory worker is no longer subservient to the layout of machine processes, but flourishes in a space of light and personal growth.

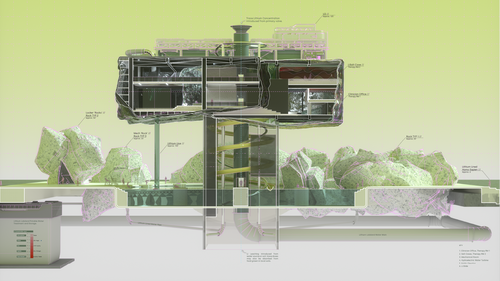

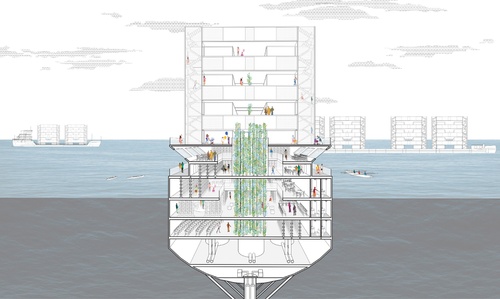

New York’s biggest export by dollar value is diamonds, which were valued at more than $13 billion last year. How can this profit contribute to the city and return to the community in the form of ethically made and environmentally conscious lab-grown diamonds? Manufactured Landscape rethinks the relationship between the factory and the city, questioning its typology. It functions as a factory, but also remediates the water edge and the area. Architecture imposes itself as the literal and figurative middle ground between production and educational infrastructure and the factory becomes a space for dialogue and transparency. Manufactured Landscape intends to oppose all the processes related to this industry, inverting the vertical and secretive diamond district into a landscape that, instead of eroding the earth, contributes to building its natural habitat and visualizes the craftsmanship and technology behind its sourcing. Each part plays a role in dialogue with the other. A Productive Space intermingles with an Educational Space over a resilient water’s edge conformed by tidal pods. A Tower sits as a distant marker and air purifier. It is a factory that understands the dynamics of sourcing and strives for the responsible creation of raw materials without the exploitation of natural resources. A factory where the combination of automation and technology plays to collaborate with humans, where labor is considered the most precious good. A machine that cooperates with the environment and understands its change and growth.

Which manufacturing system might challenge the current construction industry? The manufacturing of CLT might be a solution. MO Factory is a CLT manufacturing factory in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. Challenging the existing traditional constructions, MO factory starts with “cores” that first define the interrelationships of manufacturing spaces, and then branch to a network of spaces. There are three dimensional networks of manufacturing and circulation flows for various scales of factory spaces. MO Factory uses CLT and glulam construction methods: “stack of CLT wall panel planes” and long span glulam beams. The name “MO” is from a manufacturing process called “movable type.” There are different modulars in movable type, and the cores are designed to be the connector of modulars. Between these cores, MO Factory offers three specific areas for manufacturing the CLT: the Input Factory, Manufacturing Factory, and Output Factory. The CLT structure works both functionally and structurally. They support all the loading above them and serve as an outlet for the machine modulars. These part-to-whole strategies connect the manufacturing system and building together, but they also can work individually. MO Factory uses CLT construction methods and efficient manufacturing processes using “cores” organization to create a new construction community in Sunset Park.

9

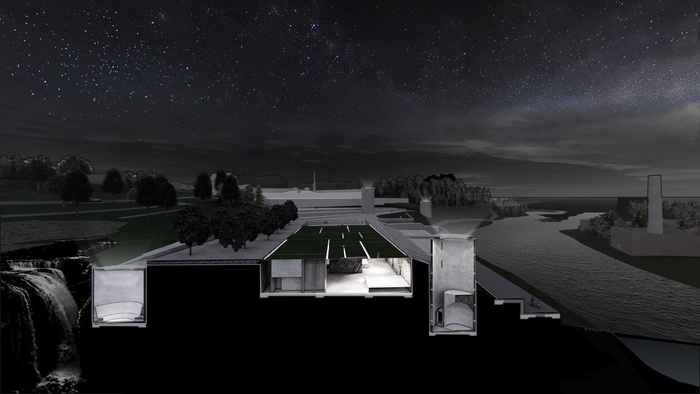

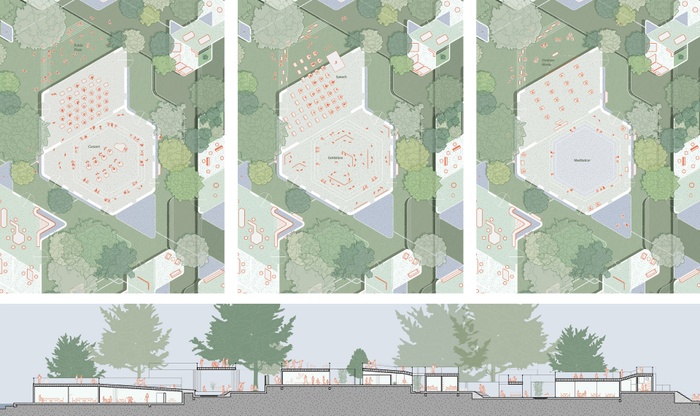

Pavilion for the Bard Prison Initiative

In this studio, students design a 12,000-square foot pavilion to house the offices of the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI) Program, located in the Hudson Valley, for a staff of 30, as well as provide an exhibition space with high ceilings and natural light. The BPI portion of the program is 5,000 square feet of offices, conference, and meeting room spaces, while the exhibition portion of the program (7,000 square feet) is open and flexible for future uses. The Hudson River School painters such as Thomas Cole and Frederic Church are cited by the client (Bard College) to be an inspiration for the ideals of the exhibition spaces.

Students: Hao Chang, Melissa Chervin, Behruz Hairullaev, Lin Hou, Xianghui Kong, Yuedong Lin, Guoyu Liu, Vera Savory, Ruijing Sun, Shengmian Wang, Xian Wu, Tian Yao

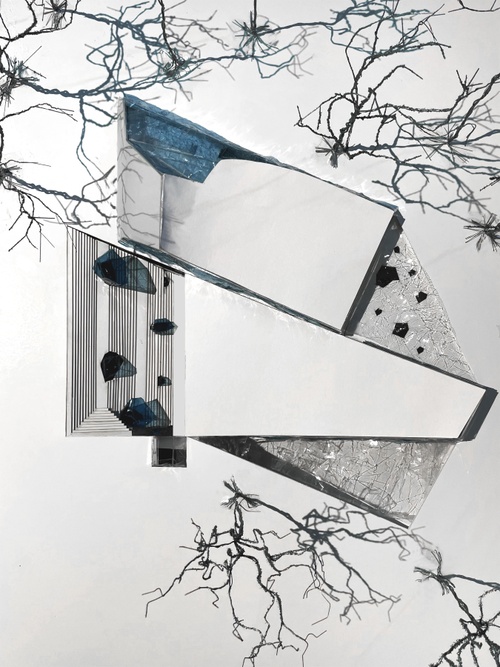

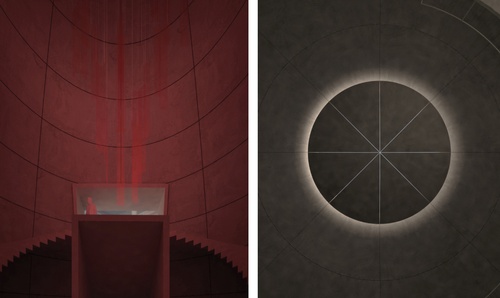

“Our proposal places the entire building underground and introduces a green, walkable platform on the rooftop. Several cast-acrylic “weights of light” are embedded into the building’s surfaces. Light reflects, refracts, and passes through the uneven surfaces of these lighting devices to create unique atmospheres and spaces for people to experience.”

“Architecture as Canvas for BPI is deeply influenced by the constantly changing phenomena of nature—one that cannot be captured in a single image.“

Iceberg: In Between the Surface

The project represents a metaphor logic from three different perspectives (volume, position, m...

“Tree Trace is an office and exhibition space that creates a meandering experience in harmony with the ruggedness and sublimity of the treescape … The gallery space is defined by a cracked glass façade system, with a structure inspired by the branches of the forest.”

“The project silently implies its immense presence through the measured space of illumination, though small in size.”

10

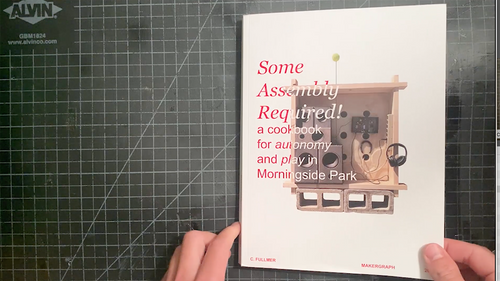

Makergraph

A site: Morningside Park, along the erased, flooded trace of the “Gym Crow,” Columbia University’s 1960s would-be gymnasium expansion at 113 street

A site: a section, from Morningside Drive/Columbia University campus to Morningside Avenue/Harlem

A site: a line, a sequence, from Morningside Avenue/Harlem to Morningside Drive/Columbia University campus

A site: your book, 1 segment of this line per week, 10 pages every week

An artifact: a single material

An artifact: a physical test, a physical fragment

An artifact: your book, 1 fragment per week, 10 pages every week

An artifact on the site: an installation

A non-monument to expose, explore, and experience

A non-monument to discuss monuments

A non-monument to discuss and disclose erasure

A non-monument to engage and connect

Through making, the studio redefines the sectional line that traces the controversial 1967/68 proposal for a Columbia University Gymnasium in Morningside Park, one that illuminated the racial inequities between two adjacent communities. This ultimately unbuilt structure is still visible and present through its foundation physical traces in the park.

Students: Refan Abed, Oliver Bradley, Ineajomaira Cuevas-Gonzalez, Alice Fang, Jonathan Foy, Cameron Fullmer, Sarah Hejazin, Marisa Kefalidis, Liang-Yu Lin, Emily Ruopp, Kai Wang

The Things That Were There And The Things That Are Still Here

The Things That Were There, and The Things That Are Still Here is my introverted journey of my...

Taking an Alternative Path: Uncovering Controversy & Societal (Un)Conditioning

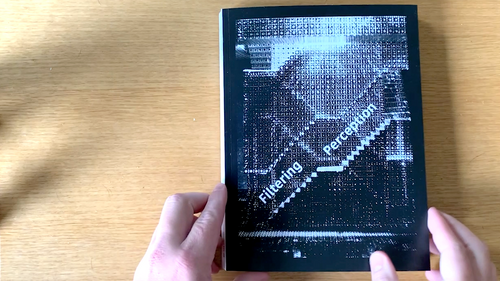

I uncover the hidden history of racism in Columbia University’s proposed “Gym Crow” building i...

11

The Street Studio

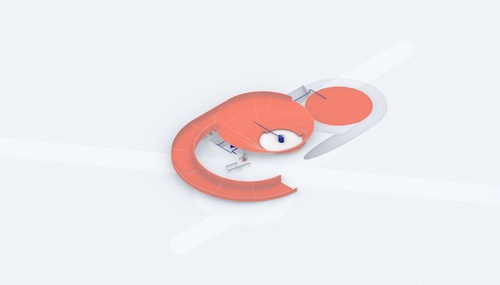

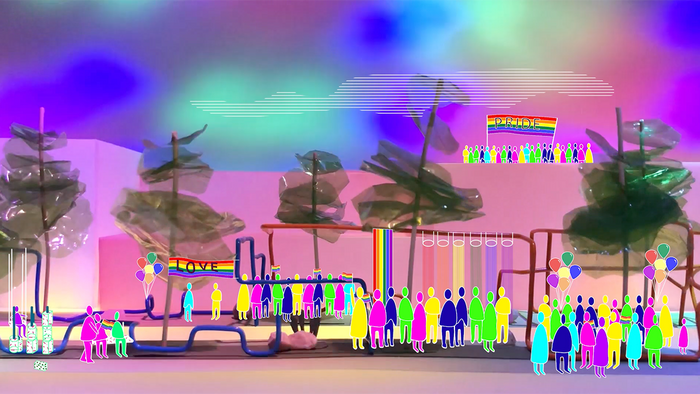

This studio researches new actors in the street, rediscovers past projects that might still offer relevance, and experiments with new technologies and typologies that can be constitutive of contemporary discourse. Following previous “Street Studios” on Fulton Mall in downtown Brooklyn and DVRC in Hong Kong, this edition takes place in the Jackson Heights neighborhood of Queens, where the streets are vibrant with life, and now the ravage of the pandemic is viscerally felt. The studio is divided into three distinct projects: Festival Street, Virtual Street, and the Infrastreet.

Students: Faisal Alohali, Audrey Dandenault, Tianyuan Deng, Chengliang Li, Lu Liu, Yuanming Ma, Tung Nguyen, Jihae Park, Taylor Urbshott, Chen Yang, Yu-Jun Yeh

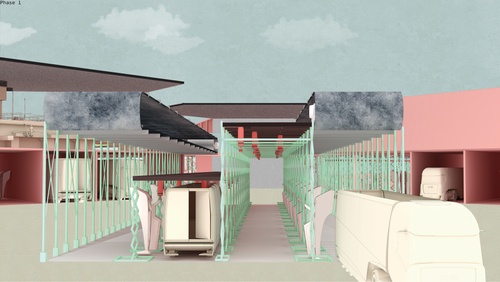

The Festival Street focuses on objects, deployed along a railing system that weaves through 82nd Street in Queens, New York. Our proposal engages with the existing urban fabric, revealing the unspoken social contracts of public space. The Rail frames vernacular interactions on the street, encouraging participation, interaction, and pleasure through leveraging the different systems of sharing already in motion on the site. It situates itself in the tension emerging from the coexistence of the formal protocols of street occupation and the popular adoption and use of the space. Defined as a heightened moment of togetherness, The Rail brings about festivity, while serving as the hyphen of formality.

“At the local level, we propose a social space between the street and the sidewalk to improve the efficiency of garbage collection and separation processes. If this metabolic process of consumption and waste operates more locally and is rooted in our daily life, the current global waste loop would shrink.”

This project positions itself to tackle the New York City vacancy crisis through the virtual occupation of Jackson Heights, Queens. Beginning with an extensive research of character on-site, a sensorial language was developed in conjunction with a digital model of the region surrounding the 82nd Street stop of the MTA 7 train. From this, a collaborative virtual street is proposed, where community members can engage in-situ using Augmented Reality (AR) and global users can interface remotely using Virtual Reality (VR).

12

Mark-Making and Place-Keeping

What are we designing, building, and maintaining? Where, why, how, and for whom? The studio Mark-Making and Place-Keeping: Erasure, Emergence, and Imagination charges designers to define a mission and vision for architecture as a practice and develop an anti-racist and decolonial approach for contributing to communities, cities, and environments that have been marked by erasure and neglect. We seek the liberation of life and people and stewardship of the environment by seeking an ethics of care in our fields of practice. For fourteen weeks, the studio participants use their time and imagination together to generate conversations, questions, ideas, images, and projects to grow their capacity and power as architects and designers to make positive change for people, places, and the planet.

Students: Erin Biediger, Matthew Brubaker, Michelle Clara, Steven Corsello, Ruochen Ji, Mark Kantai, Tristan Schendel, Jenifer Tello Sierra, Sarah Zamler

Nuburbia is located in Mableton, GA, a modern-day suburb of Atlanta on the land of the Mvskoke (Muscogee/Creek) people and the site of a former plantation. The town is named for the plantation’s owner, Robert Mable. Over the last two decades, the population of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color in Mableton has greatly increased. This, along with similar demographic changes in suburbs across the US, has prompted potentially transformative political and cultural shifts. Nuburbia promotes new approaches to occupying land and building better homes for America’s changing social and cultural landscapes. The affordable and adaptable community and homes intend to serve the wider variety of people moving to the suburbs, acknowledge the Cherokee and Creek and former plantation land they occupy, and offer new images and spaces for shaping American cultural and political ideals.

The idea of the homestead is a long mythologized part of the American dream and residual of the empowerment that land ownership brought in the new world. The homestead encapsulates the hybrid problematics black farmers and black landowners have faced in the United States following emancipation. The site of this project is the Lewis Family Homestead which was recently lost to a loophole in heirs property law after being held in the family for 125 years. This contemporary form of erasure can only be combated by reconceptualizing how members of the Black and rural community can securely and powerfully form a relationship with land in a post reparation America by tackling another “final frontier” of the American diaspora, “The New Homestead”. The New Homestead leverages the contemporary reality of global urbanism, adopts the advantages of density, and seeks to create economic, spiritual, and heritage based value. Above all The New Homestead clings to the idea that Homesteading is an ideological endeavor and the methodology of the Homestead reinforces or weakens this ideology. The New Homestead learns from the long history of homesteading, takes from the current political and socio economic realities, and is a radical new way of living on the land

Reclaiming Reclamation

Living in constant disruption of eviction threats throughout the history, Cilincing Fishing Vi...

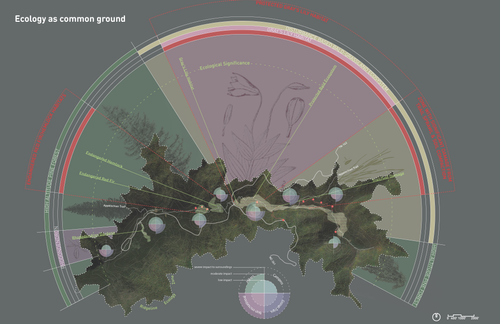

Landscape + Ecology: A lifeline for the Taita Apalis

As noted by Bird Life International Organization, biodiversity is fundamental to human well be...

Reclaiming the Neutral Ground: New Construction and Healing in New Orleans

Urban highways were never a good idea. Now, as cities all over the world look to somehow ex-fi...

Returning to Unaka

Returning to Unaka takes Roan Mountain, the Unaka Range’s highest peak, as a point of en...

Open Spaces

Jackson Heights is a neighborhood which hosts 167 languages. In 1960s, it begun to attract new...

Marktown Futures

Marktown Futures seeks justice for a community at the intersection of environmental and econom...

13

Kitchenless Stories

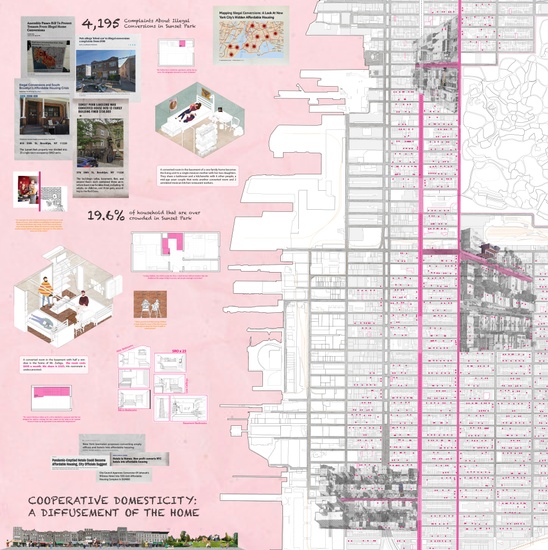

This studio analyzes how domestic architectures have empowered social and gender asymmetries, and speculates about possible spaces of resistance. The studio starts by looking at Comedores Comunitarios from Mexico City, a city-backed kitchen network that has helped to break down heteropatriarchal biases. These urban kitchens act as references to start imagining possible architectural translations within the Mexican community in the Sunset Park neighborhood, Brooklyn-New York.

Students: Alina Abouelenin, Pabla Amigo, Mark-Henry Decrausaz, Maria Nunez, Jared Payne, Maria Perez Benavides, Luis Pizano, Cheng Shen, Domenica Velasco, Tianyu Yang, Jingrou Zhao

“Common Ground is a network of spaces that serve the increasing migrant women community of Sunset Park, where they experience a lack of domestic space, job opportunities, and public infrastructure to support them. The project works together with organizations like Mixteca that aims to enrich and empower the Latinx community in Brooklyn.”

“Family Across the Border” looks at the way migration challenges our normative definitions of family and in what ways architecture can and must respond to these new realities. Looking specifically at the Mexican migrant community in New York, which predominantly comes from the state of Puebla in Mexico, this project operates on two sites––Sunset Park, New York and San Andres Azumiatla, Puebla. The proposal is not about restructuring the definition of a family, but about restructuring the architecture to fit these new definitions. In New York, the architecture becomes about how to change the way we design a traditional brownstone to meet the needs of new types of family and complex social relationships. In Puebla, the architecture is about rethinking the way in which the remittance house expands to welcome complex family dynamics that are born as a result of migrations. At the scale of the block, the proposal becomes not only about providing spaces of productivity and new sources of income, but about coming together and sharing responsibilities. It focuses on fostering community and familial/social ties, especially when blood families are separated by thousands and thousands of miles.

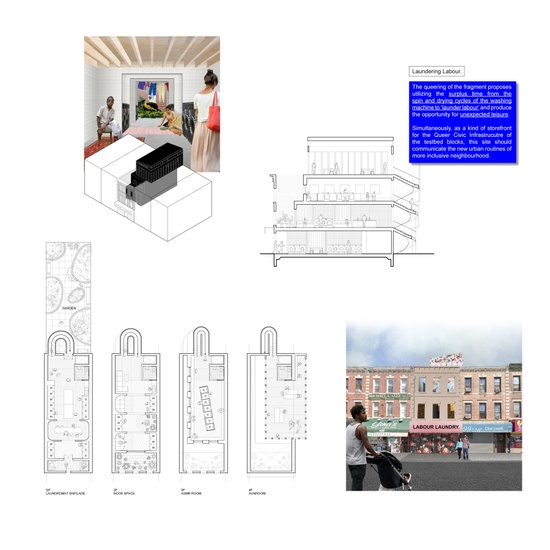

“We asked ourselves how can the practice of identity be encouraged or coaxed or enhanced. Queer civic infrastructure acknowledges the diverse protagonists in Sunset Park and proposes that queering the material and urban reality of the neighborhood can provoke new agency for its people.”

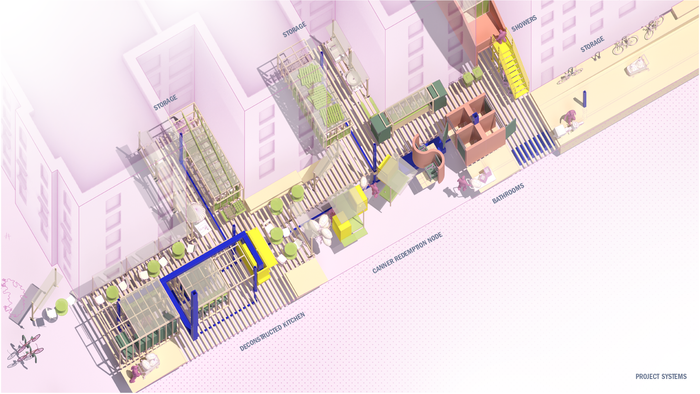

“The Net-Worked Territories comprise an urban system of logistics and restoration nodes that serve the daily needs of disenfranchised workers in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. The project departs from a mapping exercise that visualizes the patterns and tactics of three local labor groups: street vendors, canners, and delivery workers.”

14

As Little As Possible, Exercises in Open Living

What role does the design of a small open space play in the contemporary city? In this studio, students reimagine McKenna Square Park located in Washington Heights. It is neither a square nor a park. Described as a triangular plaza on the NYC Parks Department website, yet dedicated in 1985 under the purview of NYC HPD’s Bureau of Open Space Design, the park included a pavilion, a gate, a staircase, seating, and trees functioning as an open-air living room expanding the program of living beyond public housing. With very little funding, its design and construction would be maintained through contracts with the neighbors; its history is valuable for a multitude of reasons, not only for its final form. The studio proposals adopt the philosophical approach of doing as little as possible. By focusing on two scales: city to park, and architecture to industrial design through seating, and maintenance through work jackets, students design an update to the park through minimal material means. A key question for the studio is: How do durability and maintenance meet the contemporary city?

Students: Benjamin Akhavan, Margaret Bartenstein, Cong Diao, Renee Gao, Yuan Liu, Hao-Yeh Lu, Joel McCullough, Aaron Sage, Angela Sun, Liza Tedeschi, Veeris Vanichtantikul

“In the spirit of “as little as possible,” the intervention uses only four elements: the fire hydrant, play sculptures, hoses, and sandbags to create an infrastructure of play in the park.”

“Inspired by the Native American Three Sisters Planting method, which involves planting three plants together to create mutual support, our intervention focuses on building upon existing infrastructure to create a more usable park for the neighborhood. ”

“Our proposal reimagines the park through the idea of the outdoor living room, extending the programmatic needs of the existing community into the spaces of the park.”

“The design aims to make accessible and transparent the fabrication and personalization of a community-made maintenance jacket in McKenna Square Park.”

15

Something of Value, NGO Headquarters

In this studio, students design for an assumed “client,” a tech-sector company, that is endowing a new NGO of global reach to address and help solve a global issue defined by each student team. The brief is to design the NGO headquarters that the given tech company has endowed for 100 years. The building is part of the endowment and needs to be “something of value” in itself. The site is determined by each team but is located in a city that connects to issues addressed by the NGO. The NGO headquarters can use the entire site or be part of more extensive development.

Students: Camille Brustlein, Keonyeong Jang, Yi Jiang, Begum Karaoglu, Camille Lanier, Yuan Li, Junyong Park, Xinyi Qu, Xinran Shen, Yue Shi, Ziang Tang, Zhongen Xu

Our chosen NGO for Something of Value is Habitat for Humanity. The NGO takes pride in its “sweat equity” and “partnership housing” concepts, where homeowners and their communities participate in the construction of the houses they will later own. Habitat For Humanity 2.0 serves as a platform to aid in the historical and current housing crisis in New York City and Yonkers through innovative and viable interventions in the existing stock. Our headquarters for Habitat 2.0 in Yonkers is a housing expo displaying ways in which life, work, and making could coexist in a healthy and sustainable environment.

Interstitial Territories

This project aims to serve as a headquarter for the NGO Amnesty International, where refugees ...

Headquarters of World Forum for Acoustic Ecology

The WHO (World Health Organization) estimates that one million healthy life spans have been cu...

WWF 2.0

The project relocates the World Wildlife Fund’s headquarters in the center of an oil pal...

RIKOLTO HQ

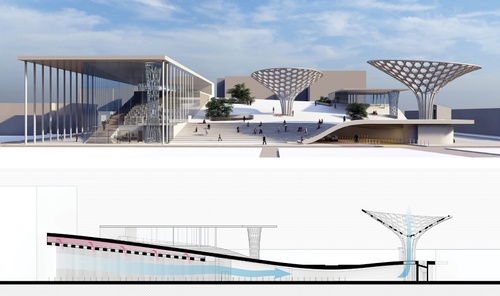

NGO Rikolto is an international NGO that focuses on agriculture and family farms. The proposed...

The Decentralized Library of Gutenberg

Various services provided by tech companies have changed our lives rapidly. However, criticism...

The Nature Conservancy 2.0

Nature Conservancy 2.0: Waco Wetland Conservation Park serves as an educational and exhibition...

Soil Foundation

The project designs for the headquarters of Soil Foundation, a new NGO proposed for the projec...

Disability Alliance Headquarter

Disability is often understood through alternative medical models in Asian countries; disabled...

“Mindspace Lab provides a space for therapeutic programs of varying sizes and degrees of privacy for students to de-stress, explore themselves, and discover their inner balance.”

16

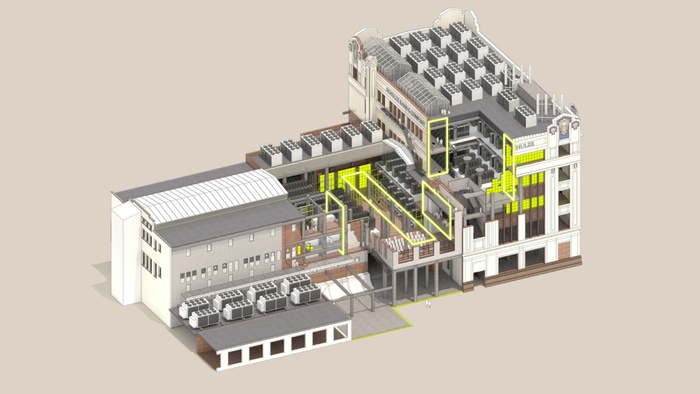

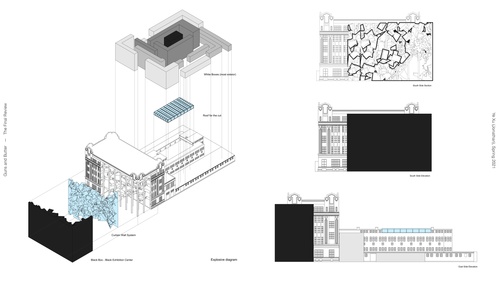

guns and butter

The studio works beyond modes of architectural production that propose some ill-defined unity and instead champions particularization, radical specificity, and delineation. guns and butter cultivates uncommon politics of naming, forging cultural practices of complexity and sustained contradiction. Students confront very particular architectural types, engaging programmatic specificity, as a way to engage blackness, capital, labor, pleasure, interiority, value, and liberation. This studio focuses on types of architecture that unsettle and perhaps totally eschew proprietary rights and facilitate shared forms of service and production; architectures—more specifically programs—that are both defensive (perhaps protective), sustaining, generous, and provide certain pleasures in a range of ways.

Students: Hong Yu Thomas Chiu, Ashley Esparza, Camille Jayne Esquivel, Jinxia Lou, Aleksandar Tomich, Tianheng Xu, Ye Xu, Yuexi Xu

“Schulze Baking Company Factory, a historic bread factory built in 1914 on the Southside of Chicago, is currently destined to be renovated and retrofitted with a data center that houses countless server racks of a commercial tenant. As a response to this condition, the project is an architectural negotiation of ownership and access to the building, which confronts the exploitative nature of the development.”

“Rather than looking at the building’s history and considering its preservation as such, I approached the design from a perspective of territorial reclamation, fortification, and excess.”

I Can’t Believe It’s Not Schulze! Reimagining the Next 100 Years of the Schulze Company Baking Plant

“I Can’t Believe It’s Not Schulze” is a campaign and proposal that foc...

The House of Butter

The House of Butter leverages and expands upon House and Ballroom Culture’s existing human and...

Exchange Islands

Give one a fish, and you feed them for a day; teach one to fish, and you feed them for a lifet...

The Restorative Justice for Criminal Justice System in City of Chicago

Chicago’s systematic and state sanctioned violence in the criminal justice system, and bias in...

17

Open Work

Half a century ago, architecture became open-ended. Buildings would change and grow, architects argued, not unlike cities. Architects embraced impermanence, promoted flexibility, timed obsolescence, and welcomed uncertainty, just as Umberto Eco proclaimed the birth of the open work, and Roland Barthes pronounced the death of the author. Architects also questioned authorship. Many would no longer strive to prescribe outcomes, let alone inscribe meanings. Against the backdrop of modern masters and modern monuments, and as a result of cultural, social, political, and technological developments, buildings became systems. Paradoxically, architects would pioneer new building types, in unprecedented ways, by openly disregarding program.

Design theories for open-ended buildings differed, but they all implied, almost invariably, free plans and modular units, as well as building components discriminated by their rate of renewal: frame versus clip-on, core versus capsule, structure versus envelope. By the mid-sixties, just a few years after speculation on openness had begun in earnest, several projects materialized. Over the following years, many changed: some according to plan, some according to no plan. Others did not. Some were demolished against the architect’s will, some preserved against the building’s principles. Today, some stand for the arguments they promoted, some for the doctrines they attacked.

This studio addresses three open-ended buildings in Japan, namely: Kiyonori Kikutake’s Miyakonojo Civic Center, Fumihiko Maki’s Senri Civic Center, and Masato Otaka’s Tochigi Prefectural Hall. The studio brief is simple. Students join a team, are assigned a building, and asked to double its surface. Do you endorse openness, and observe, refine, or redefine the original script? Do you argue against it, and monumentalize? What is at stake is to design in conversation with, and take a position on, a building and the arguments it advanced, and to tackle a longstanding question within the field, again, half a century later.

Students: Chenxi Dong, Jishan Duan, Man Hu, Tianran Li, Timlok Li, Ran Ma, Marcell Sandor, Fengyi Zhang, Jiajie Zhao, Chuyang Zhou

Looking back to look forward, we identified the artificial ground as the key focus of our rebuild. Like a stone in a pond that casts rings of ripples to its surrounding parts, the artificial ground dictated how we designed the rest of the civic center.

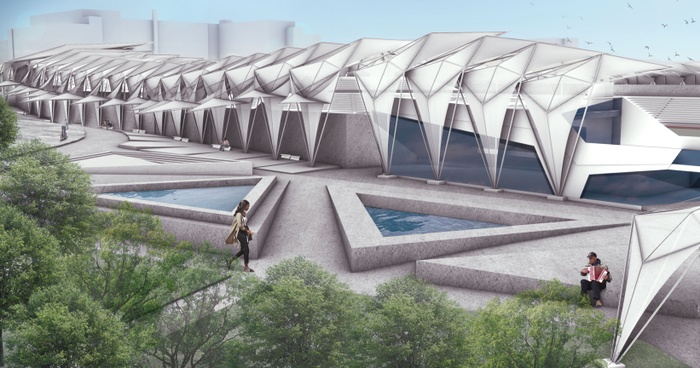

Half a century ago, metabolist Kiyonori Kikutake conceived of a building that was monstrous within its context. The Miyakonojo civic center, an icon of Kikutake’s core beliefs, was demolished in 2019 with over 80% of residents voting for its destruction. The nature of this remote semester brought a unique opportunity to revisit the “monster” who failed to metabolize, to rethink open work, and the simple task of doubling. Our team raised questions such as “How does one double something that no longer exists?” “What is the definition of Civic Space today?”. Ultimately, we propose a simple solution to rebuild the building again. We define doubling as doing it again, and as the multiplication of volume. Looking back to look forward, we identified the artificial ground as the key focus of our rebuild. Like a stone in a pond that casts rings of ripples to its surrounding parts, the artificial ground dictated how we designed the rest of the civic center. The end condition is perhaps never final; one that can not be claimed ours, but subjected to decades of future reuse and reinterpretation. In the end, doubling becomes the most sincere form of open work.

Half a century ago, metabolist Kiyonori Kikutake conceived of a building that was monstrous within its context. The Miyakonojo civic center, an icon of Kikutake’s core beliefs, was demolished in 2019 with over 80% of residents voting for its destruction. The nature of this remote semester brought a unique opportunity to revisit the “monster” who failed to metabolize, to rethink open work, and the simple task of doubling. Our team raised questions such as “How does one double something that no longer exists?” “What is the definition of Civic Space today?”. Ultimately, we propose a simple solution to rebuild the building again. We define doubling as doing it again, and as the multiplication of volume. Looking back to look forward, we identified the artificial ground as the key focus of our rebuild. Like a stone in a pond that casts rings of ripples to its surrounding parts, the artificial ground dictated how we designed the rest of the civic center. The end condition is perhaps never final; one that can not be claimed ours, but subjected to decades of future reuse and reinterpretation. In the end, doubling becomes the most sincere form of open work.

Half a century ago, metabolist Kiyonori Kikutake conceived of a building that was monstrous within its context. The Miyakonojo civic center, an icon of Kikutake’s core beliefs, was demolished in 2019 with over 80% of residents voting for its destruction. The nature of this remote semester brought a unique opportunity to revisit the “monster” who failed to metabolize, to rethink open work, and the simple task of doubling. Our team raised questions such as “How does one double something that no longer exists?” “What is the definition of Civic Space today?”. Ultimately, we propose a simple solution to rebuild the building again. We define doubling as doing it again, and as the multiplication of volume. Looking back to look forward, we identified the artificial ground as the key focus of our rebuild. Like a stone in a pond that casts rings of ripples to its surrounding parts, the artificial ground dictated how we designed the rest of the civic center. The end condition is perhaps never final; one that can not be claimed ours, but subjected to decades of future reuse and reinterpretation. In the end, doubling becomes the most sincere form of open work.

Half a century ago, metabolist Kiyonori Kikutake conceived of a building that was monstrous within its context. The Miyakonojo civic center, an icon of Kikutake’s core beliefs, was demolished in 2019 with over 80% of residents voting for its destruction. The nature of this remote semester brought a unique opportunity to revisit the “monster” who failed to metabolize, to rethink open work, and the simple task of doubling. Our team raised questions such as “How does one double something that no longer exists?” “What is the definition of Civic Space today?”. Ultimately, we propose a simple solution to rebuild the building again. We define doubling as doing it again, and as the multiplication of volume. Looking back to look forward, we identified the artificial ground as the key focus of our rebuild. Like a stone in a pond that casts rings of ripples to its surrounding parts, the artificial ground dictated how we designed the rest of the civic center. The end condition is perhaps never final; one that can not be claimed ours, but subjected to decades of future reuse and reinterpretation. In the end, doubling becomes the most sincere form of open work.

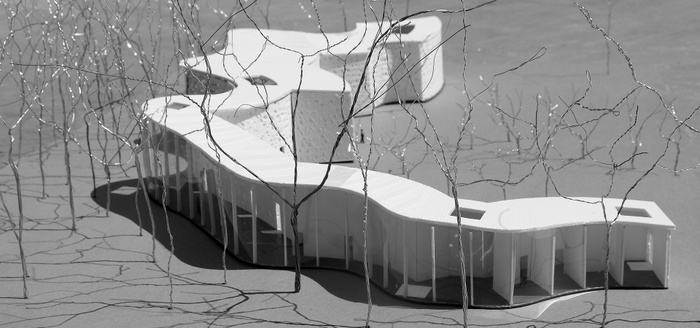

Senri Civic Center is a compound community service building designed by Fumihiko Maki in 1968, which embodied two of his essential concepts––Urban Room and Group Form. A multifunctional transparent space becomes a gathering place for citizens on the ground floor, with an extrude boundary shape that allows interior and exterior to penetrate. At the center of the building, the famous group form was embodied in replacing one gigantic core with a core bundle composed of five similar shapes. Meanwhile, it also opens the corner of the building. Maki has always been called an “urban designer” because of his insistence on taking architecture as a component of the urban environment, paying attention to the overall effect of the environment and applying urban design techniques in architectural design. Our doubling consists of three parts: empty the original building to create a void as a larger urban room; insert similarly shaped cores to Maki’s group; and duplicate in the size of the original building vertically.

Senri Civic Center is a compound community service building designed by Fumihiko Maki in 1968, which embodied two of his essential concepts––Urban Room and Group Form. A multifunctional transparent space becomes a gathering place for citizens on the ground floor, with an extrude boundary shape that allows interior and exterior to penetrate. At the center of the building, the famous group form was embodied in replacing one gigantic core with a core bundle composed of five similar shapes. Meanwhile, it also opens the corner of the building. Maki has always been called an “urban designer” because of his insistence on taking architecture as a component of the urban environment, paying attention to the overall effect of the environment and applying urban design techniques in architectural design. Our doubling consists of three parts: empty the original building to create a void as a larger urban room; insert similarly shaped cores to Maki’s group; and duplicate in the size of the original building vertically.

Senri Civic Center is a compound community service building designed by Fumihiko Maki in 1968, which embodied two of his essential concepts––Urban Room and Group Form. A multifunctional transparent space becomes a gathering place for citizens on the ground floor, with an extrude boundary shape that allows interior and exterior to penetrate. At the center of the building, the famous group form was embodied in replacing one gigantic core with a core bundle composed of five similar shapes. Meanwhile, it also opens the corner of the building. Maki has always been called an “urban designer” because of his insistence on taking architecture as a component of the urban environment, paying attention to the overall effect of the environment and applying urban design techniques in architectural design. Our doubling consists of three parts: empty the original building to create a void as a larger urban room; insert similarly shaped cores to Maki’s group; and duplicate in the size of the original building vertically.

The project was aimed to renovate the old Tochigi Prefectural Hall designed by Masato Otaka in 1969 and demolished in 2007. The old structures reflected Oatka’s idea of having traditional Japanese form with modern prefabricated concrete and were preserved intactly in the new building as a “heavy void.” We doubled the volume of the pour-in-place part of Otaka and made the solid volume light so that it becomes a ring surrounding the “heavy void” and floating above the site. The old prefectural hall was used to hold administrative offices and a conference hall. The new civic center is not only a market, but an urban connector, a cultural destination, and a gathering place for local people and visitors alike.

The project was aimed to renovate the old Tochigi Prefectural Hall designed by Masato Otaka in 1969 and demolished in 2007. The old structures reflected Oatka’s idea of having traditional Japanese form with modern prefabricated concrete and were preserved intactly in the new building as a “heavy void.” We doubled the volume of the pour-in-place part of Otaka and made the solid volume light so that it becomes a ring surrounding the “heavy void” and floating above the site. The old prefectural hall was used to hold administrative offices and a conference hall. The new civic center is not only a market, but an urban connector, a cultural destination, and a gathering place for local people and visitors alike.

The project was aimed to renovate the old Tochigi Prefectural Hall designed by Masato Otaka in 1969 and demolished in 2007. The old structures reflected Oatka’s idea of having traditional Japanese form with modern prefabricated concrete and were preserved intactly in the new building as a “heavy void.” We doubled the volume of the pour-in-place part of Otaka and made the solid volume light so that it becomes a ring surrounding the “heavy void” and floating above the site. The old prefectural hall was used to hold administrative offices and a conference hall. The new civic center is not only a market, but an urban connector, a cultural destination, and a gathering place for local people and visitors alike.

The project was aimed to renovate the old Tochigi Prefectural Hall designed by Masato Otaka in 1969 and demolished in 2007. The old structures reflected Oatka’s idea of having traditional Japanese form with modern prefabricated concrete and were preserved intactly in the new building as a “heavy void.” We doubled the volume of the pour-in-place part of Otaka and made the solid volume light so that it becomes a ring surrounding the “heavy void” and floating above the site. The old prefectural hall was used to hold administrative offices and a conference hall. The new civic center is not only a market, but an urban connector, a cultural destination, and a gathering place for local people and visitors alike.

The project was aimed to renovate the old Tochigi Prefectural Hall designed by Masato Otaka in 1969 and demolished in 2007. The old structures reflected Oatka’s idea of having traditional Japanese form with modern prefabricated concrete and were preserved intactly in the new building as a “heavy void.” We doubled the volume of the pour-in-place part of Otaka and made the solid volume light so that it becomes a ring surrounding the “heavy void” and floating above the site. The old prefectural hall was used to hold administrative offices and a conference hall. The new civic center is not only a market, but an urban connector, a cultural destination, and a gathering place for local people and visitors alike.

18

Detox USA

With the intertwining of culture and environment at stake, this studio we will analyze, reconceive, and redesign the architectures and spaces of the condition we will call “chemical modernity.” In our analysis and design, “concentration,” will serve as a marker of environmentally altered sites, political chemical histories, cultural institutions, and systems of extraction and circulation. It will also be used as a critical, spatial device that will allow a complex and perhaps unobserved relation between architecture, environment, chemicals, and artifacts to appear. The studio will ask how toxicity—in all its forms, from petrochemicals to particulates, and from opiates to air pollution—became a salient and defining feature of our modernity, and of our architecture, cities, landscapes, and territories. Toxicities may write themselves into the air, soil, water, and buildings around us, but they also accumulate within myriad systems of representation. With and through concentration, we will ask how to read toxicity not only as environmental tragedy, or as the atmospheric unconscious of modernity, but also as a sign and materialization of a culture of contamination.

Students: Farah Alkhoury, Dylan Belfield, Kshama Daftary, Nora Fadil, Jun Ito, Spenser Krut, Jiazhen Lin, Genevieve Mateyko, Ogheneochuko Okor, Lauren Scott, Florencia Yalale

Markers of Nuclear Legacies

This project responds to the topic of chemical modernity by investigating and highlighting the...